UPDATE: The screening of the 1911 film L’Inferno, scheduled for Saturday, June 23, at 3:00 p.m., has been cancelled. We apologize for the inconvenience. The other two films will screen as planned.

Filipo Argenti receiving his eternal torments in the River Styx (courtesy ©2007, Dante Film, LLC)

The Museum’s Department of Manuscripts recently opened the exhibition Heaven, Hell, and Dying Well: Images of Death in the Middle Ages. The Middles Ages was rife with terrifying imagery of hell (and a little bit of heaven). Fiendish demons, images of a pitchfork-wielding Satan, and excruciating torture populate religious texts, and their images continue to frighten to this day.

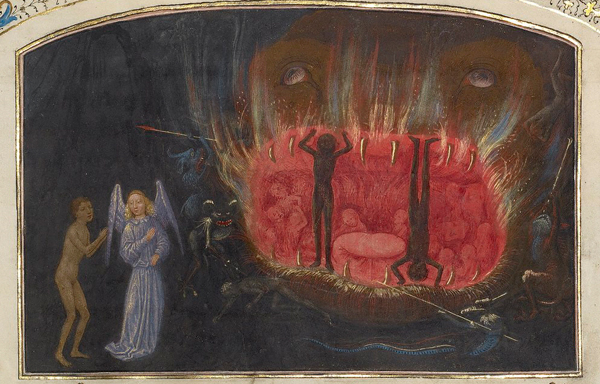

The Beast Acheron, Attributed to Simon Marmion, French, Valenciennes, 1475. Tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, and ink on parchment. The J. Paul Getty Museum

So, what gives? Why are we so infatuated with a place that offers eternal suffering? To investigate, I looked to 13th-century poet Dante Alighieri, and his magnum opus, L’Inferno. His tale of the nine circles of hell will be told June 23 and 24 at the Getty Center, where three films about the Inferno will be screened for the public. I watched the oldest, a 1911 silent film, and the newest, a 2007 film featuring one-dimensional puppets, and I left with a few thoughts about the world of fire and brimstone.

In L’Inferno (1911), director Giuseppe de Liguoro uses the new medium of film, along with pioneering special effects, to create a truly shocking depiction of hell. The dead disappear and reappear and demons fly through the sky as Dante and his companion Virgil make their way through the circles. Early pyrotechnics create a rain of fire that the blasphemers must endure, while camera tricks create false prophets with their heads screwed on backwards. Much to my surprise, the film also includes plenty of nudity, as most of the condemned don only loincloths, while others walk in the buff.

Still from L’Inferno (1911)

Even at the dawn of the 20th century, there remained a persistent fear of the otherworld, and a delight in depicting it in devilish detail. Many of the images from the film are eerily similar to images in the exhibition, such as the torture by demons in “Lazarus’ Soul Carried to Abraham” by a Master of James IV of Scotland.

Lazarus’ Soul Carried to Abraham, Master of James IV of Scotland, Flemish, Ghent or Mechelen, about 1510–1520. Tempera colors, gold, and ink on parchment. The J. Paul Getty Museum

In sharp contrast, Dante’s Inferno (2007) takes a humorous look at hell, placing many of the circles within seamy neighborhoods in New York City. In this version Dante is a remorseful drunk who wakes up in an alley to find Virgil ready to take him to the underworld.

Dante finds the entrance signage a bit daunting. Still from Dante’s Inferno. © 2007, Dante Film, LLC

Using snarky wit and more than a handful of references to the band Styx, Dante often mocks the sinners he encounters, and meets a few familiar faces. Director Sean Meredith switches out early Renaissance criminals with those of today—viewers see sinners from Pol Pot to Joseph Stalin to…Paul Gauguin? Apparently, Gauguin was in the slammer for carnality, which demonstrates the variety of sins that will get you sentenced to eternal misery. Punishments are also updated: for example, the Greek hero Ulysses, whose original punishment for deception was to be eternally consumed in flame, now has to operate a seedy puppet show in a Manhattan theater, while lovers Francesca and Paolo pay for their lusty ways by performing in their own 24-hour peep show.

Judge Minos prepares to sentence a recently condemned soul. Still from Dante’s Inferno. © 2007, Dante Film, LLC

What I found most fascinating was the mocking attitude that 2007’s Dante has towards hell. Perhaps it’s a sign of the times that hell is a less frightening prospect than it once was, and has been turned into a commentary of current political and social affairs. Regardless, both films, like the manuscripts on view at the Getty, take a novel approach to portraying in vivid detail what may or may not await us when we die.

It is curious how the Christian’s goal in life seems to be to avoid Hell, thus, reaching Heaven by default. On the other hand, Muslims also believe in Hell and Heaven. But Muslims, whether the jihadist terrorist, or the typical peaceful Muslim just trying raise her/his family and make a living, is much more focused on reaching Heaven. And Jews don’t seem to be overly concerned with reaching Heaven or avoiding Hell; they seem to leave this in God’s hands.