Cover of Album fotografico della Persia, 1860, Luigi Pesce (Italian, 1818–1891). Album of 42 photographic prints, 7 1/2 x 9 5/16 in. The Getty Research Institute, 2012.R.18

Recently acquired by the Getty Research Institute, an album of photographs taken in the late 1850s representing Tehran and ancient Persian sites is currently on display adjacent to the exhibition The Cyrus Cylinder and Ancient Persia at the Getty Villa. The album not only holds the earliest views of Persepolis, but serves as a primary visual document reflecting the historical climate surrounding 19th-century Persia, geographically caught in the political struggle between the Turkish Empire in the west, British India in the east, and the Russian Empire in the north, known as the “Great Game.”

Decorated with a Qājār-style cover (shown above), the album was presented in 1860 to the British consul in Tehran, Major-General Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson (1810-1895), by his friend Colonel Luigi Pesce (1818–1891). Pesce had been in Persia since 1848, employed by Nāsir al-Din Shah (1831–1896) to train and modernize his army. A keen amateur photographer, Pesce had originally taken many of these photographs for another album he had presented to the Shah in 1858. This first album created by Pesce is housed today in the collection of the Golestan Palace, Tehran.

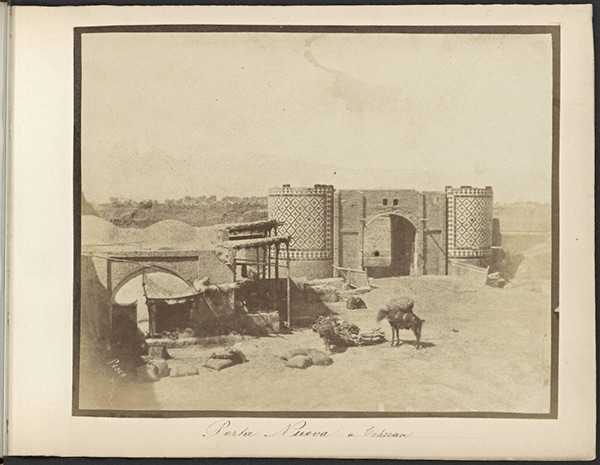

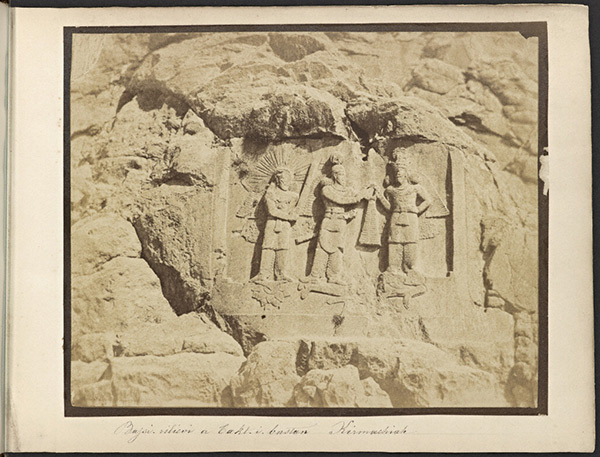

The 42 photographs in the Getty album represent some of the first ever taken of Nasīr al-Din Shah’s court, the military school, the city gates, mosques, and vicinity of Tehran, in addition to the ruins and reliefs of Persepolis and two other archaeological sites, Naksh-i Rustam and Taq-i Bāstān. Many of the monuments documented in this album, such as the military school (which Pesce directed) and the city gates, have been destroyed, and these images represent the only known photographic record.

Tehran, Entrance to Golestān Palace, 1850s, Luigi Pesce. Albumen print in Album fotografico della Persia, 7 1/2 x 9 5/16 in. The Getty Research Institute, 2012.R.18, no. 2

Tehran, Military School, 1850s, Luigi Pesce. Albumen print in Album fotografico della Persia, 7 1/2 x 9 5/16 in. The Getty Research Institute, 2012.R.18, no. 13

Tehran, Gate of the Royal Arg (Citadel), 1850s, Luigi Pesce. Albumen print in Album fotografico della Persia, 7 1/2 x 9 5/16 in. The Getty Research Institute, 2012.R.18, no. 19

Sent to Persia to secure a British presence as part of “The Great Game,” Henry Rawlinson, the recipient of the album, played a key role in the strategic rivalry between the British and Russian Empires vying for supremacy in Central Asia. Besides being an accomplished military officer and diplomat, Rawlinson was an exceptional linguist who has been described as the father of Assyriology, because his translations of the famous Behistūn inscription enabled a collective scholarly deciphering of cuneiform.

As a visual artifact with a historically precise provenance and a known maker and recipient, the Getty album helps to frame the early history of photography in Persia and provide insight into how images contributed to imperial agendas and nation building. More than merely a series of photographs, the album narrates multiple stories that together provide new insights into the rich history of Persia from the ancient period to the modern.

Taq-i Bāstān, Kermānshāh, 1850s, Luigi Pesce. Albumen print in Album fotografico della Persia, 7 1/2 x 9 5/16 in. The Getty Research Institute, 2012.R.18, no. 41

My colleague Leila Moayeri Pazargadi and I will publish a paper on this album, “Picturing Qājār Persia: A Gift to Major-General Henry Creswicke Rawlinson,” this spring in The Getty Research Journal. | Abstract

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.