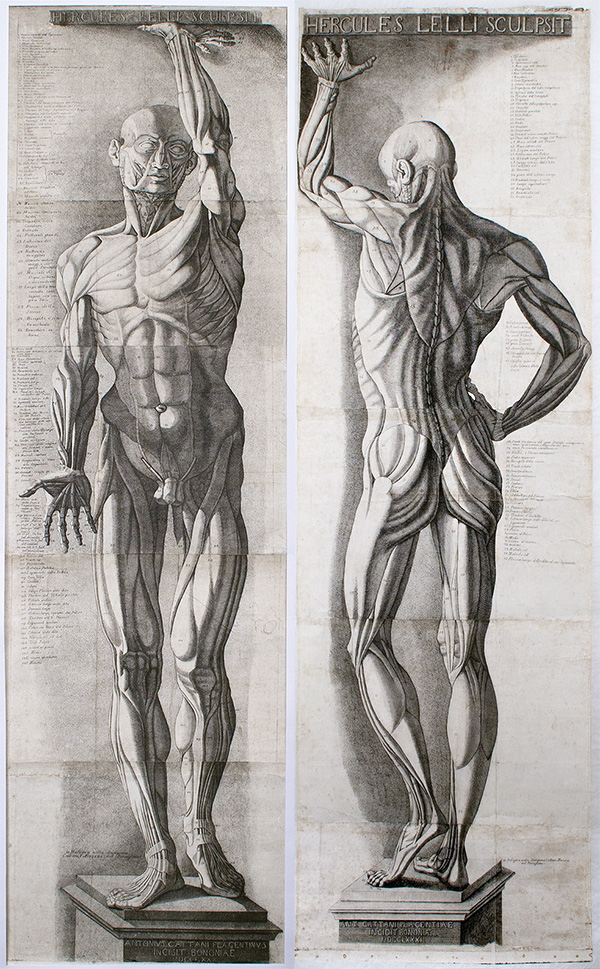

Anatomical Figures, 1780 (left) and 1781 (right), Antonio Cattani (Italian, active 1770s–1780s). Engravings, in frame 212.7 x 78.7 cm. The Getty Research Institute, 2014.PR.18 and 2014.PR.19

Before the advent of photography, X-rays, or the plastinated figures in Body Worlds, human beings relied on anatomical sculptures and prints to understand the human body. Three multi-sheet prints of life-size figures that recently entered the Getty Research Institute’s special collections were created during a particularly lively period in the exploration of this topic: 18th-century Italy.

At the intersection of science and art, each of the prints features a life-size écorché, meaning “flayed” or without skin, arranged in a stylized posture to show off muscles and bones.

At the intersection of science and art, each of the prints features a life-size écorché, meaning “flayed” or without skin, arranged in a stylized posture to show off muscles and bones.

Bodies in Wax and Wood

Louis Marchesano, curator of prints and drawings at the Getty Research Institute, stands on a chair next to the three anatomical prints to demonstrate the life-size scale of the figures. The prints came with their original rollers, which were used for both storage (when rolled up) and display (when unrolled and hung from a wall).

Antonio Cattani created these engravings in the 1780s based on sculptures by painter, architect, and coin maker Ercole Lelli. An artist of many talents, Lelli was famed for his wax and wood models of anatomical figures.

Lelli examined at least 50 cadavers in the process of sculpting the two figures known as Hercules I and Hercules II, identifiable by the inscriptions atop each print. The sculptures were created for the “anatomical theater” of the medical school at the University of Bologna, a room dedicated to the teaching of anatomy through dissections of human bodies.

Hercules I and II remain in this location to this day, although Cattani probably prepared copies for his engravings while the sculptures were on display at the Academy of Fine Arts in 1780 or 1781. For, in addition to training medical students, wood-and-wax figures were also useful in training a different class of professionals: artists. In fact, from the Renaissance on, numerous artists contributed to the study of anatomy through dissections and the creation of two- and three-dimensional replicas.

Cattani, the printmaker, highlighted Lelli’s significance to the field by including the sculptor’s name in spot of honor on the top, while relegating his own name to the pedestal on the bottom.

Are They Accurate?

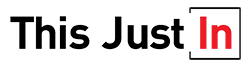

Anatomical Figure (detail), 1781, Antonio Cattani (Italian, active 1770s–1780s). Engraving, in frame 212.7 x 78.7 cm. The curator consulted two doctors about these engravings. They believe the artist intentionally included anatomical anomalies for education reasons, as the prints were used as teaching aids.

The purpose of Cattani’s prints was primarily instructional. On each engraving, for example, numbers are keyed to names listed in Italian beside each écorché, to help students master the parts of the body.

Still, the engravings include hints that instructional license was also at play. In the front facing Hercules écorché, the figure’s knees are presented from two different perspectives: the left knee is viewed correctly from the front, while the right knee is presented from the back, offering a physically impossible mix of front and back. This disjunction was presumably intentional.

Other anatomical anomalies throughout the prints more likely reflect the limitations of scientific knowledge at that point in time. Despite the extreme precision of the prints, much remained to still be discovered about human anatomy two and a half centuries ago.

Toward a More Human Art

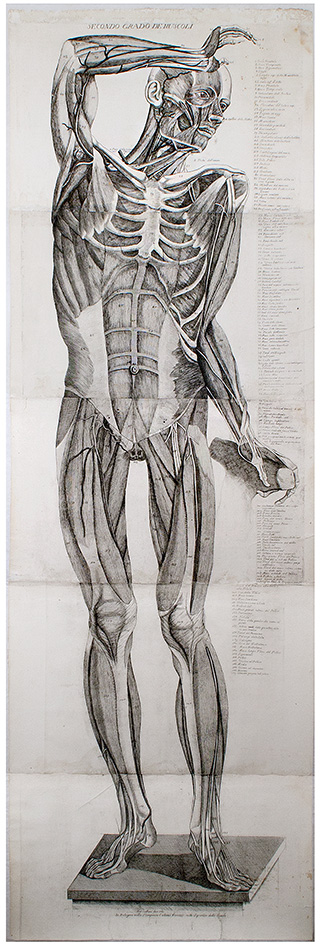

Secondo grado de muscoli, 1781, Antonio Cattani (Italian, active 1770s–1780s). Engraving, in frame 212.7 x 78.7 cm. The Getty Research Institute, 2014.PR.19

The third print in the series focuses on human musculature. Technically, it is not an ecorché, for it shows the second layer of muscles far beneath the skin. The print may be based on one of the wax models created by Lelli in the 1740s and 1750s for Bologna’s Institute of Sciences. Pope Benedict XIV, known for his commitment to advancing the arts and sciences, commissioned these models with the intent of providing young artists with more opportunities to study the human body.

Since the Renaissance, Italian art academies included anatomical study in the training of artists with the objective of generating more realistic, lively figures in their art. By investing in these young artists, Benedict XIV’s commissions served to improve the quality of the arts in Bologna—and, through the spread of Cattani’s prints, throughout Italy and beyond. These prints preserve a fascinating moment in the history of art and science, through the meeting point of anatomy.

As part of the Getty Research Institute’s special collections, these prints are available to study by qualified researchers. Plans have not yet been made for their display in the galleries.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.