The Getty recently acquired a magnificent copy of the Book of Deeds of Jacques de Lalaing, essentially a biography of the greatest knight of the late Middle Ages. The manuscript had resided in a private collection for hundreds of years, and was only known through black-and-white photos of a publication dating from 1914 (learn more about the manuscript and its origins). Because I’ve made a scholarly specialty of Flemish illumination of the 16th century, the date and locale of this manuscript, I was responsible for the research in preparation for the manuscript’s acquisition. The book begins with a monumental frontispiece of the text’s author at his desk hard at work.

It is almost certain that this illumination was painted by Simon Bening, the most celebrated manuscript artist of the 16th century. Bening was the favored artist of patrons across Europe, famed for his poetic landscapes, stolid figures, psychological subtlety, and fleck-like brushwork (his work was highlighted in the 2003 exhibition Illuminating the Renaissance).

Since the Lalaing manuscript had received almost no scholarly attention, my job was to find stylistic and compositional links to the known manuscripts by Bening. I found abundant close comparisons for the seated figure, the conception of the room’s interior, and the way in which the surfaces of objects were painstakingly evoked.

Left: The Author in his Study (detail), about 1530–40, Simon Bening. Tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, and ink; 14 5/16 x 10 5/16 in. J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 114, fol. 10. Acquired in honor of Thomas Kren. Right: The Annunciation (detail), about 1524–30, Simon Bening. Tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf on parchment; 6 5/8 x 4 1/2 in. J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 13v. Digital images courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

For instance, our graduate intern, Alexandra Kaczenski, who was working with me, noticed that the still life of flowers in a majolica vase on the window ledge was painted in a very similar way to one found in a prayer book by Bening from the same period in the Getty’s collection.

Detail of monkey in The Author in His Study, about 1530–40, Simon Bening

In addition, even the tiniest of details is given artistic attention of the highest order. In the outdoor courtyard with the waiting horse, a tiny blue blob is just visible atop a red hitching rail used to tether horses. Under extreme magnification, it becomes evident that the blue blob is actually a tiny monkey dressed in a monk’s habit with a delicate cable chaining him to the wall behind. The monkey is less than two millimeters tall.

Another hallmark of Bening’s work is the way that light plays a major role in the image, spilling across the desk and the floor. And curled up in the perfect warm patch of sunlight is a fluffy dog with his head resting on his paws http://www.tbcredit.ru. I’m a dog lover myself, and so I couldn’t help noticing during the course of my research that this particular dog kept cropping up in Bening’s late work, which provided additional evidence that the image was by Bening.

There is no lack of confirmation that Bening liked dogs in general. Dogs in medieval illuminations often have a symbolic meaning, usually relating to the theme of loyalty, but in Bening’s works, they seem to pop up everywhere, mostly without a distinct symbolic function.

They race alongside huntsmen:

Calendar page for November with a miniature of a nobleman returning from a hunt, from the Golf Book (Book of Hours, Use of Rome), about 1540, Workshop of Simon Bening, Netherlands (Bruges). The British Library, London. © The British Library Board, Additional MS. 24098, folio 28v

They peek out from behind the skirts of noblewomen:

Genealogical Tree of the Kings of Aragon (detail), 1530–34, Simon Bening. The British Library, London. © The British Library Board, Additional MS. 12531, folio 4

They coolly oversee tumultuous religious events (although here the calm greyhound may well serve as an emblem of faithfulness in contrast to Saint Peter’s dramatic denial of Christ):

The Denial of Saint Peter, about 1525–30, Simon Bening. Tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf on parchment; 6 5/8 x 4 1/2 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 123v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Certainly, then, Bening was fond of enlivening his works with the presence of all sorts of dogs. But this particular dog, with red ears, spots on a white coat, and a feathery tail struck me as special. In the frontispiece of the Lalaing manuscript, the dog’s physical appearance and personality are evoked with great care, from the gradations of white in areas of his fur to the pensive expression on his face, to the tiny pink point of his nose.

Detail of dog in The Author in His Study, about 1530–40, Simon Bening

This dog seemed to occur over and over again in various of Bening’s works. I could find no other specific dog appearing in his images with this frequency and regularity.

I found him as a little puppy in the arms of a lady:

Calendar page for March depicting falcon hunting (detail), from the Hennessy Hours, 1530–40, Simon Bening. The Royal Library of Belgium, Ms. II 158, folio 3v. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels (Belgium), cliché Y000070. Photo: Jean-Luc Elias, I.R.P.A.

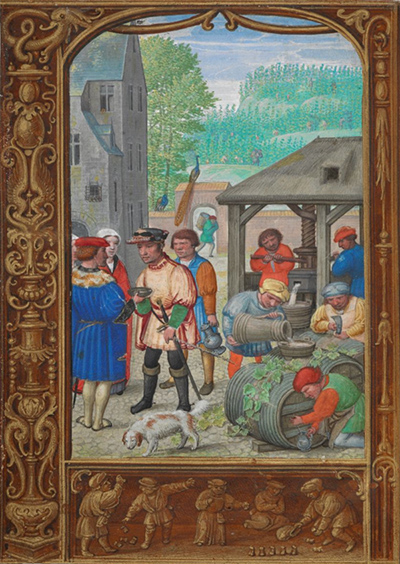

I found him in the countryside:

Calendar page for October with a miniature of wine making, from the Golf Book (Book of Hours, Use of Rome), Workshop of Simon Bening, Netherlands (Bruges). The British Library, London. © The British Library Board, Additional MS. 24098, folio 27v

I found him in the city:

Christ Led from Herod to Pilate, about 1525–30, Simon Bening. Tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf on parchment; 6 5/8 x 4 1/2 in. J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 147v. Digital Image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

In fact, I found him almost a dozen times in different books, wagging, snuffling, hunting, and sleeping.

Calendar page for July depicting falcon hunting, from the Hennessy Hours, 1530–40, Simon Bening. The Royal Library of Belgium, Ms. II 158, folio 7. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels (Belgium), cliché Y000070. Photo: Jean-Luc Elias, I.R.P.A.

Clearly Bening liked dogs, and this dog appears in different guises throughout his work over a period of about 15 years. Could this be Simon Bening’s own dog? Of course, there is no way to prove this, and it simply could have been that Bening often reused this dog from a workshop model drawing, but it is a fun possibility. After all, the convincing way in which Bening depicts the dog’s movements and antics indicates that he may have been using a model from life. And what would be more convenient than observing your own pet?

The dog seems to resemble a modern-day Brittany Spaniel.

Left: Brittany spaniel. Photo courtesy of Breeder Retriever. All rights reserved. Right: Detail of dog in Christ Led from Herod to Pilate, about 1525–30, Simon Bening

Although the Brittany breed wasn’t developed until the 17th century in France, the characteristic playful manner, markings, and feathery coat make a good comparison. And what is more natural than a Brittany curling up in the sun like the dog in the Getty’s manuscript?

Left: Brittany spaniel puppy. Photo courtesy of and © Laura Nicholson, lnphotography.ca. All rights reserved. Right: Detail of dog in The Author in His Study, about 1530–40, Simon Bening

We will likely never know whether Simon Bening had a pet dog, or whether he thought to incorporate him into his manuscript illuminations if he did. But based on the sheer multitude of dogs that appear in his images (and I only ever found two cats), I think we can safely posit that Simon Bening was a “dog person.” As for the fluffy red-and-white canine who appears frequently in his late work, I think I’ll give him a name. As I found in Kathleen Walker-Meikle’s book Medieval Dogs (The British Library, 2013), over a thousand suitable names for dogs were given in a medieval manuscript called The Master of the Game. One of them, which seems entirely appropriate here, has inspired me to give this Bening doggie the name “Smylefeste.” He surely brings a smile to my face.

This new acquisition, open to the frontispiece featuring the dog (aka “Smylefeste”), is currently on display until September 25 at the Getty Center in the same gallery as Things Unseen: Vision, Belief, and Experience in Medieval Manuscripts.

In the meantime, my research will now turn to the other images in the manuscript, which are by a different artist. This artist is not a member of Bening’s workshop, but seems much more influenced by the movement known as Antwerp Mannerism. His work is characterized by a painterly quality seen in the handling of the figures and landscapes, the bright colors, and the dramatically conceived compositions. The illuminations are at the same time pervaded by a Mannerist sensibility most clearly seen in the loving care lavished on the costumes and settings.

Left: Jacques de Lalaing Arriving at a Joust before the King of France (detail), about 1530–40; Circle of Master of Charles V. Tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, and ink; 14 5/16 x 10 5/16 in. J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 114, fol. 40v. Acquired in honor of Thomas Kren. Right: Jacques de Lalaing Kneeling before the Dauphin of France (detail), about 1530–40; Circle of Master of Charles V. Tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, and ink; 14 5/16 x 10 5/16 in. J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 114, fol. 91. Acquired in honor of Thomas Kren. Digital images courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

There are even a couple of dogs featured in his compositions. Who knows, maybe they will help lead me to identifying this artist as well.

Possibly the artist’s dog; perhaps a key donor’s pet.

It appears too small to be a Brittany Spaniel, perhaps a Continental Toy Spaniel, now known as Phalène, or Papillion. They are commonly found in paintings and are one of the oldest breeds.

This dog is terrific, though the shape of his head differs from the Brittany spaniel’s. There were other continental spaniels during this period!

Watch for my study of sculpted dogs in northern Spain: “Eternal Devotion: the stone canine companions of gothic Burgos,” in Laura D. Gelfand (ed) Our Dogs, Our Selves: Dogs in Medieval and Early Modern Society, Leiden: Brill (in Press. Publication scheduled 2016)

All the dogs discussed have specific characteristics of dog breeds that originated in Spain, and their use can be understood to communicate ideas for reasons of temperament .

I heard about this book recently and am very much looking forward to reading it! Beth

I am THRILLED that the Getty bought this manuscript. I saw it in the sale catalog from Switzerland and was thinking it was probably beautiful, and the Bening miniature of Toison d’Or is gorgeous. So looking forward to seeing it person.

Thanks for a delightful essay on this charming subject.

Well done, Elizabeth. This is a charming and wonderful article.

This is a wonderful article. As an art historian, I love playing art-detective. This makes the works truly come alive.

Smylefest… so full of character, so clearly loved!

Thanks for a wonderful and inspiring article! Now I wish I had a dog to hug…

Take a look at the work of Jan Steen the Dutch 17th century painter. A similar looking dog appears in most of his paintings. These are thought to be Kooikerhunde a common dog in 16th and 17th Holland. It is so common in his paintings that it is known as Jan Steen’s dog.

Interesting! Much more than a pictorial device, in this case.

I certainly believe this could be his dog. If you were a painter with a beloved dog, wouldn’t you put him in your paintings when you could? I love your article and your take on this dog-loving artist. Thank you!

Wonderful images – I believe the dog is probably a Nederlandse Kooikerhondje. http://www.akc.org/dog-breeds/nederlandse-kooikerhondje/#

Wonderful story thank you. I think that the dog may be kooikerhondje, which is a spaniel-type of old Dutch dog breed, with the same markings and “feathery fur” as has the lovely little dog in Bening’s paintings. Take a look: http://www.kooikerhondje.nl/en/ras/

The Brittany is not a spaniel. It has been officially called simply a Brittany since 1983.

The dog depicted however is far more likely to be an almost identical dog called a Kooikerhondje.

It was a popular breed in the Netherlands during the 16th century and is to this day considered to be the favourite Dutch medium/small dog.