The recent Death Salon at the Getty Villa encouraged attendees to face the reality of death and to make end-of-life choices—before reaching the end of life. Taking this admonition to heart, we in the Manuscripts Department have meditated on the greatest images of death, dying, martyrdom, and resurrection in the Getty’s collection.

Death was at the forefront of the medieval mind, as explored by a recent exhibition in the our manuscripts gallery. In a world of violent military encounters, horrifying pestilences, and a religious tradition whose visual imagery centered on crucifixion or saintly torture, the devout prepared their minds, bodies, and souls daily for death’s cruel sting.

Daily Death

Deathbed Scene and Office of the Dead in the Spinola Hours, about 1510–20, Master of James IV of Scotland. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 18, fols. 184v–.;185

Office of the Dead: The artist of this manuscript conceived of the open book as a single canvas for a complex narrative about death and burial. At the bottom left, a young man is found by the specter of death when he falls from his horse. In a kind of X-ray view above, the corpse appears laid out on a bed, surrounded by mourners. Across the page at right, the man’s funeral bier appears in a church, whose front has also been stripped away to reveal the interior. Below, the sarcophagus rests in the crypt of the church. The image introduces the Office of the Dead, recited daily to prepare the soul for a death that can come at any time. —Elizabeth Morrison

The Three Living and the Three Dead and Decorated Text Page in the Crohin-LaFontaine Hours,about 1480—85, Master of the Dresden Prayer Book or workshop. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 23, fols. 146v–147

The Living and the Dead: While out hunting on horseback, three knights in the prime of their youth are shocked and distressed to encounter three hideous corpses. Even if we look to the beautiful foliate borders of the page to escape this disturbing image, hidden among the plants, flowers, and insects are skulls—a reminder that beauty and youth are fleeting and that death spares no one. —Christine Sciacca

From Womb to Tomb

A Religion of Death and Life

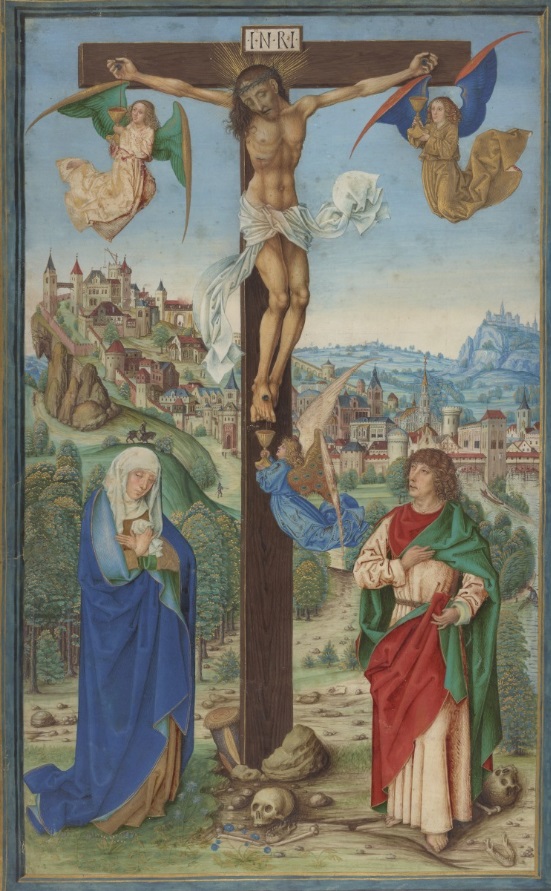

The Crucifixion, 1475–1500. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 52, recto

Jesus on the Cross: The most prevalent image of death in medieval art is that of Jesus on the cross. In this particular portrayal, the emotions of those witnessing the event are almost bound up in the figures’ draperies. The mournful Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist are clothed in heavy immovable fabric, while Jesus and the angels are luminous and airy, with textiles floating in the wind. The drapery alludes to the combined sorrow and celebration of Jesus’s life and serves a reminder of the complexity of death and the teachings at the center of Christianity. The image would have introduced the text for the celebration of the Mass, which commemorates Christ’s body and blood through bread and wine. Look closely at the angels: they catch Christ’s blood in golden chalices, a literal connection to one of the serving implements in this ritualistic rite commemorating death and life. —Andrea Hawken

The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, about 1430–40, Master of Sir John Fastolf. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 5, fol. 36v

Saint Sebastian’s Arrows: Saint Sebastian of Avla was martyred under the Roman Emperor Diocletian (around A.D. 288), who commanded that the Christian be bound to a stake and shot with arrows. Although Sebastian was left for dead, he is thought to have miraculously survived the torment. While some artists are more modest in their estimation of the number of arrows inflicted on poor Sebastian, this illuminator has covered nearly every inch of the martyr-saint’s body, making the miracle that much more profound. In the background of the scene, Pope-Saint Fabian (A.D. 236–250) is about to be beheaded. His feast is celebrated on the same day as that of Saint Sebastian (January 20), in whose church in Rome one finds the pope-saint’s tomb. In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, Saint Sebastian was often a symbol of hope in times of widespread disease because of his ability to defend Christians from the “arrows” of plague and pestilence. —Rheagan Martin

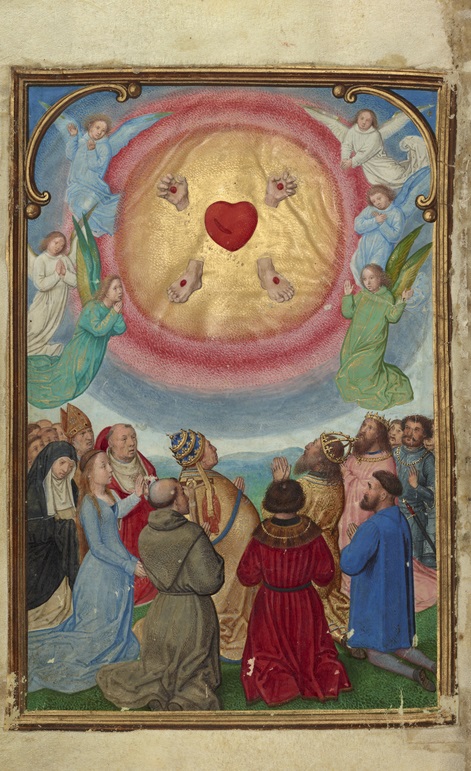

The Worship of the Five Wounds in the Prayer Book of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg, about 1525–30, Simon Bening. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 335v

The Wounds of Christ: This strange and powerful image accompanies a prayer dedicated to the wounds of Christ. The grievous injuries Christ suffered on the cross are visually distilled and shown as disembodied hands, feet, and a side wound on a heart. Devotion to these wounds, which were considered to be the essence of Christ’s humanity, became increasingly popular among late medieval and Renaissance faithful. A group of adoring angels and a crowd of people representing various social classes—kings, clergy, aristocrats, and monks—regard the extraordinary vision, which would have reminded Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg, the book’s original owner, of the Second Coming of Christ and would likely have inspired reverence and awe. —Kristen Collins

Comments on this post are now closed.