Left: Initial S: The Conversion of Saint Paul, attributed to Pisanello and the Master of the Antiphonal Q of San Giorgio Maggiore, probably northern Italy, about 1440-50. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 41, verso. Right: The Italian wine region of Colli Piacentini in the Emilia-Romagna province. Photo: Francesco Secchi (Wikimedia Commons)

Art and wine are a natural pair. In the Renaissance, princes and other high-ranking nobles selected the greatest of both to enhance their own magnificence.

From the Latin magnum facere, the word magnificence means “doing something great.” Magnificence was considered a civic virtue and thus those with power and funds spent large sums on building projects, works of art in various media, and other examples of patronage, such as lavish banquets or festivals where wine flowed in abundance. At the northern Italian courts such as Ferrara, Milan, and Venice, the artistic concept roughly equated to costliness of materials, the quality of artistry, originality, and an overall splendor meant to impress. This story is told in the current Getty manuscripts exhibition Renaissance Splendors of the Northern Italian Courts, which includes some of the most dazzling hand-painted books from the time.

The natural link between art and wine led to the conception of a culinary workshop and wine tasting course focusing on northern Italy during the Renaissance, led by the two of us—a manuscripts curator (Bryan) and a Certified Clore Sommelier and Certified Cicerone®, aka wine and beer specialist (Mark). This course is held tomorrow (Saturday, April 11) and repeats June 13. Here’s a sneak-preview tour through three of Italy’s great wine regions, with art and wine picks you can pair at home.

Map of Italy with the major cities of the north in white type.

The Backdrop

During the Renaissance, the changing fates of individuals and courts could be equated with a great wheel, ever-turned by the hand of Fortuna (or Lady Luck): one rose to the top while another fell and was crushed beneath. Round and round the wheel spun. Through this Renaissance “game of thrones” (if you will), marquises, dukes, counts, princes, prelates, and other nobles attracted innovative artists into their circles and commissioned works of art as signs of magnificence. Dining parties, lavish gardens, and a penchant for fashionable dress were other outward displays of greatness, meant to outshine or compete with the splendors of other courts. Here’s a quick look at four courtly centers and wine-making areas.

The Wheel of Fortune from the Visconti-Sforza Tarot Deck (The Brera-Brambilla Visconti Tarot), between 1440s and 1470s. Photo: Nekonekojudith, Wikimedia Commons

Emilia-Romagna: Ferrara

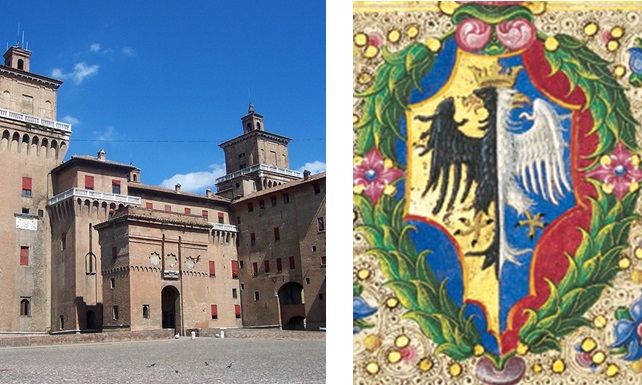

Castello Estense and the Este coat of arms. Photo: Geobia (left; Wikimedia Commons) and the Bible of Borso d’Este (right; Wikimedia Commons)

Rulers: During the Renaissance, Ferrara was controlled by the Este family, who ruled as marquises until 1471 and then as dukes.

Art: Ferrara was an important artistic center, and the Getty collections are particularly strong in works made there. These include illuminated manuscripts, ranging from the tiny Gualenghi-d’Este Hours to a monumental page from the Antiphonary of Cardinal Bessarion, and panel paintings, like the intimate scene of Saint Jerome by Ercole de’ Roberti.

Fun fact: The Bible of Borso d’Este, illuminated by Taddeo Crivelli and Franco dei Russi (and a team of illuminators), cost far more than the remarkable zodiacal fresco cycle in the Palazzo Schifanoia.

Wine: The glorious, warm climate and fertile soil of Emilia-Romagna’s plains—crowned with the Po River to the north that cascades into gradual hills in the south—shapes rich and individualized wine styles, the most eclectic in northern Italy. The major red (rosso) wine varietals and styles in this region are Lambrusco, Sangiovese di Romagna, and Barbarossa, while the top white (bianco) wines are Albana di Romagna, Trebbiano, Malvasia, and Chardonnay.

Tasting: Malvasia from Castello di Luzzano by Giovannella Fugazza called ‘Tasto di Seta,’ Colli Piacentini, Rivescala, Emilia Romagna (2013).

Lombardy: Milan and Mantua

Castello Sforzesco and the Visconti-Sforza arms. Photos: Idéfix and G.dallorto, Wikimedia Commons

Mantua skyline and the Gonzaga coat of arms. Photos: Massimo Telò and Andreas Praefcke, Wikimedia Commons

Rulers: From 1395 to 1447, Milan was ruled by the Visconti family of dukes; they were supplanted by the Sforza dukes, who ruled until 1524 (when the Spanish Hapsburgs took over rule of the Duchy). The Gonzaga Marquises ruled Mantua until 1530, when they also became dukes.

Art: Milan is a city of fashion and is associated with some of Leonardo da Vinci’s great masterpieces (including The Last Supper, commissioned by Duke Ludovico Sforza for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie). To the east, Mantua is renowned for the extensive fresco cycles by Pisanello and Andrea Mantegna, and the city boasts a powerful relic connected to the Gonzaga family: the Holy Blood of Christ.

Wine: Lombardy is the richest in lakes of all the regions of Italy. The area’s climate and terrain vary across the province, but it is generally a cool, continental clime, ideal for crisp, mineral-forward sparkling whites, as well as lake-warmed, robust, flavor-layered red wine styles. Major red wines include Barbera, Nebbiolo, and Pinot Nero, while the dominant whites are Chardonnay, Pinot Bianco, and Pinot Grigio.

Tastings: Franciacorta Ca’ del Bosco, Cuvée Prestige, Brut, Erbusco, Lombardia, (NV); Lambrusco from Lo Duca, Reggio Emilia, Emilia Romagna (NV); Garda rosé blend (chiaretto) from Costaripa ‘Rosa Mara,’ Classico, Moniga, Lombardia (2012).

The Veneto: Venice

Palazzo Ducale and Saint Mark and the Lion, patron saint and emblem of the Venetian Republic. Photos: Petar Milosevic, Wikimedia Commons

Rulers: For over a millennium, the Doge ruled as chief magistrate and leader of the Venetian Republic, often referred to as La Serenissima (the most serene). The Doge was elected for life.

Art: Light is a major characteristic of Venetian painting, whether drawn from the radiant gold of the city’s Byzantine heritage or inspired by the luminous effects of the many canals, lagoons, and waterways. During the Renaissance, as today, the Island of Murano is a major destination for lovers of glass.

Wine: The Alps in the north protect the region from the harsh northern European climate. The Veneto’s Dolomite Mountains, known for their scenic beauty, are matched by the region’s dynamic wine makers, who ambitiously create styles that appeal to international palates and vinifications trends. Among the major red wines are Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Corvina, Molinara, and Rondinella. For the whites, we often think of Garganega, Trebbiano di Soave, Tocai, and of course, Prosecco.

Tastings: Soave from I Stefanini from the Tessari family called ‘I Selese,’ Classico, Monteforte d’Alpone, Veneto (2013); Valpolicella from Le Salette, Classico, Fumane, Veneto (2012); Raboso red blend from Marinali of Villa Sandi, Crocetta del Montello, Veneto (2009).

Left: Goblet, Italian (Murano), about 1500. Inscribed in Latin VIRTUS LAUDATA CRESCIT, “Virtue grows with praise.” The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.DK.534. Center: Ewer, Italian (Murano), late 15th or early 16th century. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.DK.512. Right: Goblet, Italian (Murano), 1475–1500. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.DK.533.

If you’re in L.A., we hope you’ll consider joining us for an in-person tasting and tour of the northern Italian manuscripts on view. The event repeats on Saturday, June 13 from 1:00 to 4:30 p.m. We’d love to raise a glass with you!

Comments on this post are now closed.