The Getty Museum recently hosted a study day for graduate students and faculty from Bayan Claremont, one of the first American graduate schools dedicated to educating American Muslim scholars and religious leaders.

The institution reached out to the Museum to inquire whether our collections included Islamic art. We do have a medieval Qur’an in our collection that we thought would be of great interest—so we invited students and faculty to join us in the Manuscripts Study Room on a Saturday to take a look. We displayed several pages from this Qur’an, made in Tunisia in the 800s, alongside folios from a lectionary (book of Bible readings for religious services) made in Germany at the same time.

Together, these books allowed for a discussion of the importance of text and daily recitation in the devotional practices of Muslims and Christians over a thousand years ago, and a consideration of how objects in museums can be engaged by religious observers today.

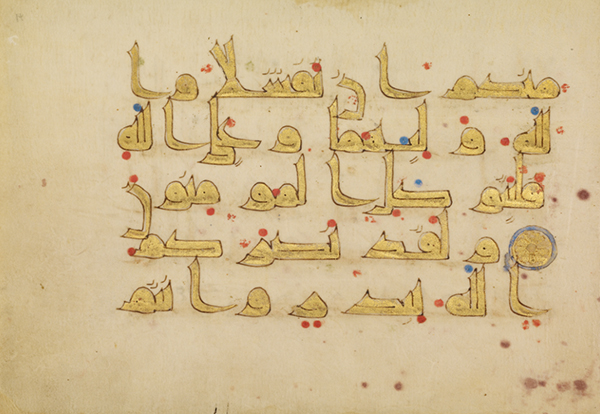

Decorated Text Page, leaf from a Qur’an, probably made in Tunisia, 9th century. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig X 1, fol. 10

Decorated Text Page, leaf from a Gospel lectionary, made in the Rhine-Meuse region, early 800s. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IV 1, leaf 3

The scribe of the Qur’an, produced within about 150 to 200 years of the Prophet Muhammad’s death, began by writing the Kufic script (an angular way of writing Arabic) in ink. The words were later filled in with gold leaf. Vowel sounds are indicated with blue and red dots, while ink-drawn accent marks help distinguish consonants of the same basic form. Dr. Ovamir Anjum, a visiting professor at Bayan Claremont who is also chair of Islamic Studies and professor of the intellectual history of Islam at the University of Toledo, explained that these additions helped ensure a careful interpretation of the words by the reader.

The lectionary contains the Gospel readings arranged according to the church calendar. Created under the reign of the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne, it was painted purple to resemble costly dyed codices from the Byzantine Empire. The text (written in brass) is difficult to read today, but would have been much more legible in the 9th century. Side-by-side, the lectionary and the Qur’an sparked discussions about the role of manuscripts in religious services and the importance of the spoken word for activating the text on the page, and in so doing uniting the terrestrial with the celestial.

This study day highlighted how devotional practice can intersect with object-centered meaning-making and curatorial practice. In the Museum’s education department, we strive to extend encounters with art objects beyond solely aesthetic form or historical context, encouraging visitors to understand objects in social, ritual, and intellectual contexts beyond the museum. When people relate their impressions of an artwork to previous knowledge and experience, memories of this encounter are retained longer, and are applied more often to subsequent experiences. According to Bayan student Gail Ferguson, “The experience was truly unique – the intimate setting allowed me to engage with the manuscripts organically and holistically. Everyone should be able to experience the Qur’an at least once the way I was able to at the Getty.”

In the manuscripts department, our strong collection of books produced for a medieval Christian readership (Western European, Byzantine, Armenian, Coptic, Ethiopian) has inspired numerous exhibitions, lecture programs, symposia, discussions, and study days with scholars, religious devotees, and lay audiences from all walks of life. Our manuscripts gallery becomes a space where objects from diverse traditions can be placed in context, in contact, or in dialogue with each other.

Building Bridges between Faith and Art

This study day was an important step for us toward wider access, encouraging visitors to bring more of their perspectives to bear when encountering and making meaning with collection objects. It also directly aligns with previous bridge building between the Museum and various religious communities.

Last fall, in connection with the Heaven and Earth exhibition at the Getty Villa, members of Los Angeles’s Greek Orthodox community gathered to make an exhibition-inspired mosaic and attend a scholarly symposium related to Greece’s Byzantine heritage. The Museum also hosted an Art and Religion Study Day, which brought together over 150 graduate students and scholars of religion and art history with artists to co-investigate material religion across disciplines.

Photo by Leena Butt

Medieval Manuscripts Alive

![]() As part of the Bayan Claremont study day, Dr. Anjum performed a recitation of the Surah contained in the Getty Qur’an, re-activating the manuscript towards its original sacred intent for the first time in years! As participant Ismail Akbulut said afterwards, “It was a special moment to see the Qur’an from the 9th century, and the recording of the recitation of the Qur’an was especially moving.” Dr. Anjum’s voice is now part of our Medieval Manuscripts Alive audio initiative, which features readings and recitations from Getty manuscripts by specialists in the languages of the Middle Ages. You can read more about this occasional series here. Dr. Anjum recited portions of Surah 3 from the Qur’an, which you can listen to below.

As part of the Bayan Claremont study day, Dr. Anjum performed a recitation of the Surah contained in the Getty Qur’an, re-activating the manuscript towards its original sacred intent for the first time in years! As participant Ismail Akbulut said afterwards, “It was a special moment to see the Qur’an from the 9th century, and the recording of the recitation of the Qur’an was especially moving.” Dr. Anjum’s voice is now part of our Medieval Manuscripts Alive audio initiative, which features readings and recitations from Getty manuscripts by specialists in the languages of the Middle Ages. You can read more about this occasional series here. Dr. Anjum recited portions of Surah 3 from the Qur’an, which you can listen to below.

Decorated Text Page, leaf from a Qur’an, probably made in Tunisia, 9th century. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig X 1, fol. 1

The Getty Museum’s collection provides many windows into the world’s diverse and intertwined histories. This study day opened yet another avenue for people to engage with the collection and one another.

_______

Medieval Manuscripts Alive is an occasional series featuring readings from Getty manuscripts by specialists in the languages of the Middle Ages.

Comments on this post are now closed.