“Then appears a singular being having a man’s head atop the body of a fish,” Odilon Redon. Plate V in The Temptation of Saint Anthony, 1888, lithograph. 17.7 x 12.5 in. (sheet). The Getty Research Institute, 2011.PR.30

My job as research assistant to Marcia Reed, chief curator at the Getty Research Institute, and Louis Marchesano, curator of prints & drawings, might be described as “research becomes eclectic.” In addition to investigating a wide array of potential acquisitions across the period of A.D. 1500 to the present, I’ve spent much of the past eight months researching the diverse prints now on view in The Getty Research Institute: Recent Print Acquisitions (through September 2). I’ve always struggled to pick a “favorite” historical period or artist, and honestly this job only makes that more difficult!

Inevitably, however, there are particular artists whose work I find especially appealing. I have recently become immersed in the graphic work of Odilon Redon (French, 1840–1916) thanks to working on an additional display featuring his prints in the West Pavilion of the J. Paul Getty Museum, which went up at the same time as the GRI print show.

In darkness and light: View into the gallery of The Getty Research Institute: Recent Print Acquisitions. Odilon Redon’s print Lumière occupies its own spotlit nook on the tenebrous back wall (far right, in frame).

It seems that every modern period and place produces an auteur whose visions veer toward the realms of the strange, the dreamily dark, and the surreal. During the first half of his career Redon filled this role, gaining acclaim for creating bizarre and haunting visuals based on literature and his own imaginary scenarios. Flaming eyeballs float before a mountain range; fishlike creatures sport huge human heads and tiny hands; a giant man pauses outside a window while two small figures gesture towards him. Redon made these visions concrete via the lithograph, exploiting that medium’s ability to achieve dramatically contrasting blacks and whites.

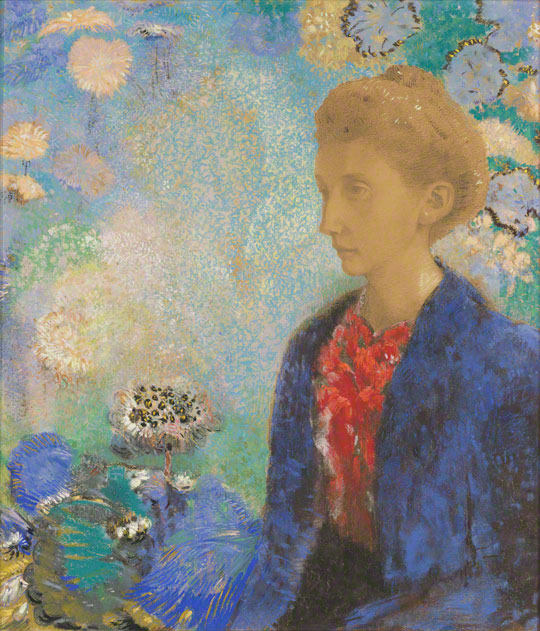

But then, in a gradual and eventually definitive shift, Redon seems to have truly embraced the belle in Belle Epoque. Around 1890, he began producing fewer black and white lithographs (belles in their own ways, of course) in favor of lighter, more woozily ethereal and Edenic imagery rendered in luminous, deep colors, as demonstrated beautifully by a pastel and pencil drawing in the collection of the Getty Museum.

Baronne de Domecy, Odilon Redon, about 1900. Pastel and graphite on light brown laid paper, 24 x 16 11/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2005.1

Redon’s colorful work retains a certain odd dreaminess, but more in the sense of a fantastic daydream than an otherworldly nightmare. With recent acquisitions of Redon prints by the GRI, visitors to the Getty can now glimpse both sides of Redon: the dark and the light.

Redon experimented obsessively with the tonal extremes of the lithograph, seemingly in the hopes of articulating—via literal lights and darks—the range and particularly the extremes of psychological experience. Unlike woodcuts or intaglio prints such as etching and engraving, lithography is a planar medium in which the artist doesn’t have to incise a metal plate or cut into a plank of wood. The method is much closer to drawing, in that the artist works with a greasy crayonlike tool on a flat surface (most often a stone, hence the “litho”). In this way the artist determines which parts of the stone the equally greasy ink will cling to, and can then make multiple impressions from one design.

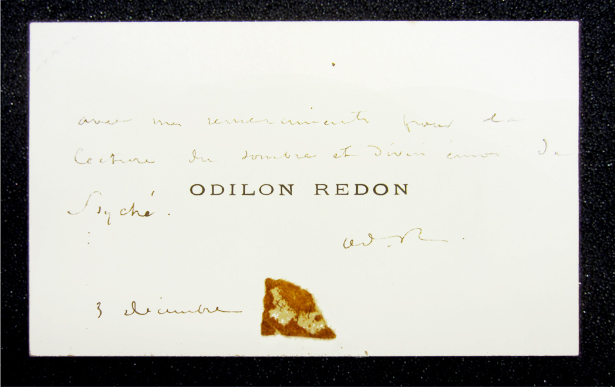

Having begun his artistic endeavors with charcoal drawings he called “noirs” because of their intensely dark tones, Redon’s lithographs pick up where his early drawings left off. He was extremely exacting when it came to overseeing the printing of his work, and made sure that each impression’s blacks were sufficiently (and by sufficiently, I mean really) dense. Some of the prints almost have a three-dimensional quality. The GRI’s newly acquired prints by Redon were created during this period: 1888’s 10-print portfolio The Temptation of Saint Anthony and 1893’s standalone print Lumière. The acquisition joins several Redon letters in the collection, which includes the carte-de-visite shown below.

Odilon Redon, annotated carte-de-visite thanking Jules Bois for sending him a book on the occult, 1891. The Getty Research Institute, 87-A556

Redon loved literature, and was an active member of the Parisian Symbolist literary circles during the 1870s and 1880s. He often created series of prints based on literary works, and was drawn to darker subjects; one of his favorite authors was Edgar Allan Poe. Knowing this, a friend gave him a copy of Gustave Flaubert’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony, a work which even today often garners the descriptor “trippy.” Equal parts play and novel (yet impossible to actually stage), Flaubert’s exhaustively researched text dramatically recreates a night in which Anthony, alone in the desert, experiences a variety of temptations orchestrated by the Devil. There are, of course, women; there are scientists; there are numerous false gods and prophets; and the Devil himself makes an appearance.

The project seemed to have haunted Flaubert, who published three separate versions of it over the course of his career. As part of my research I read the final 1874 version of the book that guided Redon’s prints—my first taste of Flaubert—and I can affirm that it is quite unlike anything I’ve ever read! I got the sensation of diving into the database of an incredibly brilliant, encyclopedic mind, and feeling the seams about to burst with arcane knowledge; yet there is an intense control with which the near-psychedelic visions are dispensed in the text.

The sheer abundance of ancient references in what is a rather slim work is mind-bending, and each sentence seems to contain multiple possibilities for a visual imagining. With lines like “…first, a puddle, then a prostitute, the corner of a temple, the figure of a soldier, a chariot with two rearing white horses,” Flaubert could keep any artist bent on capturing the essence of Saint Anthony very busy, and Redon eventually published three separate suites of prints inspired by lines from Flaubert’s text.

The GRI’s is the first suite issued, and this particular copy was originally owned by André Mellerio, a major collector and eventual biographer of Redon (you can see Mellerio’s diamond-shaped stamp on the lower right of the prints). The first print shown below, Plate VI, was Redon’s personal favorite; in it, Death, crowned by roses, hovers amidst an impenetrable and seemingly infinite black. Even in the final lithograph of the series, Plate X, when Anthony sees the face of Jesus Christ in the rising sun and realizes that he has survived the night of torment, the intense black of that night remains palpable beyond the rays of the sun.

“This is a skull with a crown of roses. It resides atop a woman’s torso of pearly whiteness,” Odilon Redon. Plate VI in The Temptation of Saint Anthony, 1888. Lithograph, 17.7 x 12.5 in. (sheet). The Getty Research Institute, 2011.PR.30

“And in the same disc of the sun shines the face of Jesus Christ,” Odilon Redon. Plate X in The Temptation of Saint Anthony, 1888. Lithograph, 17.7 x 12.5 in. (sheet). The Getty Research Institute, 2011.PR.30

As I mentioned, the entire suite is now on display in the Getty Museum, hung on the wall adjacent to James Ensor’s amazing painting Christ’s Entry into Brussels (completed in 1888, the same year Redon issued his prints). For an added bonus, we’ve also hung four prints by Max Ernst from his suite Natural History (1926) beside Redon’s Saint Anthony.

In addition to illustrating Redon’s influence on the Surrealists, the group of artists with whom Ernst was associated, the pairing also exposes some intriguing thematic connections. Utilizing collages made from traces of real-world objects (captured via pencil rubbings called “frottages”), the 34 collotype prints in Natural History depict a primordial world untouched by man. One of Anthony’s greatest temptations is the desire to escape from human consciousness by becoming a creature existing in a pre-human world like the one Ernst depicts, graced by God but free of temptation and sin—or to become pure matter, free of all consciousness. Anthony laments,

“Would that I had wings, a carapace, a shell, – that I could breathe out smoke, wield a trunk, – make my body writhe, – divide myself everywhere, – be in everything, – emanate with all the odours, – develop myself like the plants, – flow like water, – vibrate like sound – shine like light, – assume all forms- penetrate each atom – descend to the very bottom of matter, – be matter itself!”

Just this small sampling of Flaubert’s text reveals its hallucinatory and exhilaratingly visual qualities, which Redon captures so well. You can see the entire set through the GRI’s Digital Collections.

In Lumière, the other Redon print recently acquired by the GRI, things lighten up, as the title (“Light”) suggests—but only a little.

Lumière, Odilon Redon, 1893. Lithograph, 24.6 x 17.8 in. (sheet). The Getty Research Institute, 2011.PR.25

The viewer becomes a double voyeur, left to contemplate the two small men in the foreground as well as the large meditative head outside the window that they seem to be discussing. Linked to dreams and imagination, Redon’s subject illustrates his shared interest in the Symbolist’s exploration of forces mystical, occult, and spiritual. The “meaning” of the print seems open to the viewers’ own deciphering. Maybe the “pensive head” (as Redon initially called the print) represents the illumination or light that the individual thinker can cast upon society. At the same time, this individual (and especially the artist, Redon may be saying by extension) must always exist outside the collective. The print was made in an edition of 50, and as soon as the printing was complete, it was available at the Librairie de l’art independent, where proponents of mysticism and symbolism gathered (and no doubt came up with many other interpretations of this print!).

If you’d like to do some of your own deciphering, I encourage you to come see these prints in person. It’s amazing just how vibrant a work on paper composed of only blacks and whites can be—reproductions do not do Redon’s masterful prints justice. And while you’re there, amongst so many wonderful examples from Western printmaking, you, like me, might have to add a few onto your ever-growing list of “favorites.”

“Lumière” is on view at the GRI as part of the show “The Getty Research Institute: Recent Print Acquisitions,” while all ten prints from “The Temptation of Saint Anthony” are installed in the J. Paul Getty Museum (both through September 2, 2012).

Really informative post thank you so much. Redon is an artist that i have admired but never really spent time getting to know. This will surely find its way into my practise in some way. The Flaubert piece sounds perfect to add to my to read list for my current projects . Thanks again for a great post

best

Dean