Statue of a Youth (the Mozia Charioteer) (detail), 470–460 B.C., Sikeliote (Sicilian Greek). Marble, 181 cm high. Courtesy of the Servizio Parco archeologico e ambientale presso le isole dello Stagnone e delle aree archeologiche di Marsala e dei Comuni limitrofi—Museo Archeologico Baglio Anselmi. Reproduced by permission of the Regione Siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana. Dipartimento dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited

Throughout 2013, the Getty community participated in a rotation-curation experiment using the Getty Iris, Twitter, and Facebook. Each week a new staff member took the helm of our social media to chat with you directly and share a passion for a specific topic—from museum education to Renaissance art to web development. Getty Voices concluded in February 2014.—Ed.

If only this ancient statue could speak…we could ask him who he is, and how he ended up on the tiny island of Mozia, just off the western coast of Sicily. The first work of art that most visitors to our exhibition Sicily: Art and Invention between Greece and Rome will encounter, this over-life-size marble youth may be the finest work of Greek sculpture surviving from antiquity. Transfixing you with a self-confident gaze, the figure proudly flaunts a muscular physique, a single fragmentary hand pressing the soft flesh of the hip. The incredible skill of the stone-carver is evident in the delicate pleats of the gossamer gown that clings sensuously to the body beneath, revealing much more than it conceals.

Delicate pleats outline a strong, muscular leg and knee. Detail of Statue of a Youth (the Mozia Charioteer). Courtesy of the Servizio Parco archeologico e ambientale presso le isole dello Stagnone e delle aree archeologiche di Marsala e dei Comuni limitrofi—Museo Archeologico Baglio Anselmi. Reproduced by permission of the Regione Siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana. Dipartimento dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited

Mozia (called Motya in ancient times) was a Carthaginian base, a stepping stone for the North African settlers who inhabited western Sicily. Nowadays, the whole island of Mozia is an archaeological site, preserving the remnants of a flourishing trading post that acted as a cultural crossroads between the Carthaginians, Greeks, and native Sicilian peoples.

We still vividly remember our first visits out to Mozia, gingerly stepping into a small boat for the short crossing past tile-covered pyramids of salt and windmills to the shores of the island. Thousands of years before, the statue must have made a similar passage to Mozia, still only accessible by sea, but from where…Selinous, Akragas, Himera?

A view of modern-day Mozia, Sicily. Photo: ah zut on Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Unearthed in 1979 during excavations of the area between a sanctuary and a potter’s workshop, lying on his back in a pile of rubble, the so-called Mozia Charioteer has been the subject of ongoing debate. Was he carved by a Greek sculptor, or a Sicilian Greek artist? How did he end up on Mozia? And most of all, who is he? The fiercest discussion has centered on his identification: is he a hero or a god, a victorious athlete or a ruling tyrant from one of the Sicilian metropolises?

Statue of a Youth (the Mozia Charioteer). Courtesy of the Servizio Parco archeologico e ambientale presso le isole dello Stagnone e delle aree archeologiche di Marsala e dei Comuni limitrofi—Museo Archeologico Baglio Anselmi. Reproduced by permission of the Regione Siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana. Dipartimento dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited

This April, a distinguished group of scholars from Sicily, other parts of Italy, and the U.S. gathered at the Getty Villa to address these questions. In the weeks before, rumors had been swirling that our speakers would propose some new theories.

A detail of the hand resting on the hip. Detail of Statue of a Youth (the Mozia Charioteer). Courtesy of the Servizio Parco archeologico e ambientale presso le isole dello Stagnone e delle aree archeologiche di Marsala e dei Comuni limitrofi—Museo Archeologico Baglio Anselmi. Reproduced by permission of the Regione Siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana. Dipartimento dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited

Classical art is millennia old, but there is still much to study, learn—and debate.

Our study day, “Rethinking the Mozia Youth,” began in the seminar rooms at the Villa, where we have scholarly convenings. Clemente Marconi, a professor at the New York University Institute of Fine Arts, argued for the traditional interpretation of the youth as a victorious charioteer. As evidence, he pointed to the great number of Sicilian Greek coins showing a charioteer wearing similar garb of long belted garment, with a victor’s wreath on his head.

Caterina Greco, director of the Archaeological Park of Selinunte, agreed that the youth was a charioteer, but proposed that instead of a local athlete, the statue portrays the mythical Pelops, admired for his great beauty and prowess as a charioteer.

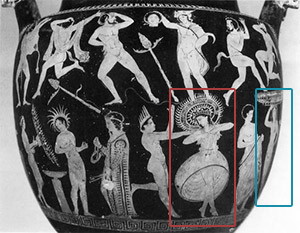

Detail of the Taranto krater, 400s B.C., Karneia Painter. Greek, made in South Italy. Terracotta, 72 cm high. Taranto, Museo Nazionale Archeologico

And the dissenting opinion? UCLA professor John Papadopoulos offered a radical rethinking, arguing that he is a dancer, performing a sacred ceremony in honor of Apollo Karneios and raising his arm to support a large basket on his head. He based this argument on the presence of fully five ancient holes drilled in the statue’s head, which suggest that it was once adorned with something larger and heavier than a helmet or meniskos (protective disk). John made his case by showing this detail of a Greek vase—arguing that the youth might once have worn a headdress as dramatic as the figure at center (called out in red), with a pose like the figure at the far right (in blue). Put the basket of the red figure on the pose of the blue one, “and you’ve got the Motya Youth.”

Jerry Podany, the Getty’s senior conservator of antiquities, followed, discussing the mount that he engineered to protect the statue from earthquake damage—as great a risk in western Sicily as here in Los Angeles. Liberated for the first time from its previous support system, the Mozia Youth and can be fully appreciated as he was meant to be, from all sides. Intense conversation continued in the galleries, in the presence of the statue itself. Here professor Andrew Stewart from the University of California at Berkeley pointed out that the sculptor would have required a huge block of marble to carve the piece, demonstrating the expense and effort required to bring the stone from the Greek island of Paros, where the stone was quarried, to Sicily.

The conclusion? We agreed to disagree, and that research should continue. But while the true identity of the Mozia Youth may be lost in the mists of time, he is unquestionably one of the world’s world’s most breathtaking ancient sculptures.

As co-curators of the exhibition, we have both been thinking about the Mozia Charioteer for more than three years, when we began planning the exhibition. Our love affairs with Sicily began much earlier, however. We both first encountered Sicily as students, spending the summers on archaeological excavations. These glorious long weeks afforded time to explore the island. With our groups of keen archaeologists, we visited sites and museums in the sizzling heat, occasionally washing the dust off alongside holiday-makers on the bustling beaches. Today, we feel enormously lucky and proud to have the Mozia Charioteer here with us in Malibu until August 19. Take the boat trip to Mozia another time (it’s well worth it!), but don’t miss the chance to come by and see him and the other Sicilian treasures on view in the exhibition. Perhaps he’ll whisper his secrets to you.

The youth and I. Installation view of Sicily: Art and Invention between Greece and Rome at the Getty Villa. Artwork: Statue of a Youth (the Mozia Charioteer). Courtesy of the Servizio Parco archeologico e ambientale presso le isole dello Stagnone e delle aree archeologiche di Marsala e dei Comuni limitrofi—Museo Archeologico Baglio Anselmi. Reproduced by permission of the Regione Siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana. Dipartimento dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited

________________

Alexandria Sofroniew, assistant curator of antiquities at the Getty Museum and co-curator of the exhibition Sicily: Art and Invention between Greece and Rome at the Getty Villa, talks about her journeys in Sicily.

What an incredible piece of antiquity! Whenever I look upon works of this quality, I am always inspired to bring my best to my own work – whether it’s writing, blogging, or even the more seemingly mundane and less glamorous tasks of dealing with my children, supporting my co-workers or just making the bed. Truly, what an inspiring piece of art. Thank you for featuring.

Thanks so much for sharing, George. It does make one appreciate the craftsmanship of the anonymous ancient sculptor who produced such beautiful handiwork, and I agree, makes one want to strive to be as creative!

Mozia Charioteer: I will be in Sicily from mid-September through mid-October 2013. I had been planning to visit Mozia to see this sculpture, but discovered that it is on display at the Getty. Not having time to make the trip to Los Angeles, I would like to see it on this visit to Sicily. Please advise re the plans to return the Charioteer to Mozia, such as the date when it is expected to be on display in Mozia so I can plan my itinerary accordingly.

Thank you for any information you can provide.

I first saw the Mozia sculpture in Mozia during a three week tour of Sicilian antiquities. I was captivated by the sensuousness of the piece. It was by far the highpoint of my visit. I am glad to see that it is available for viewing at the Getty