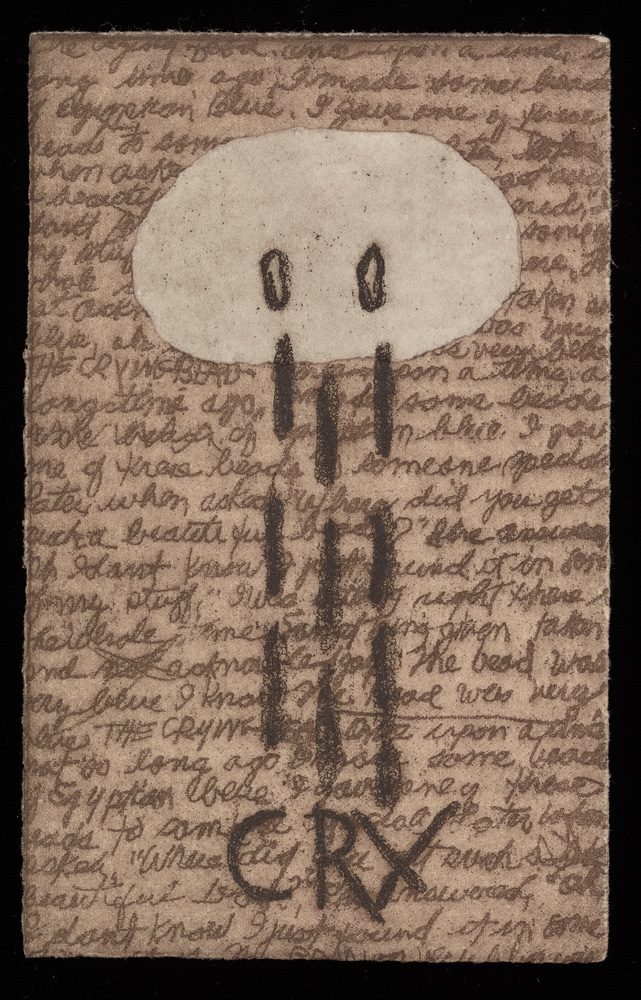

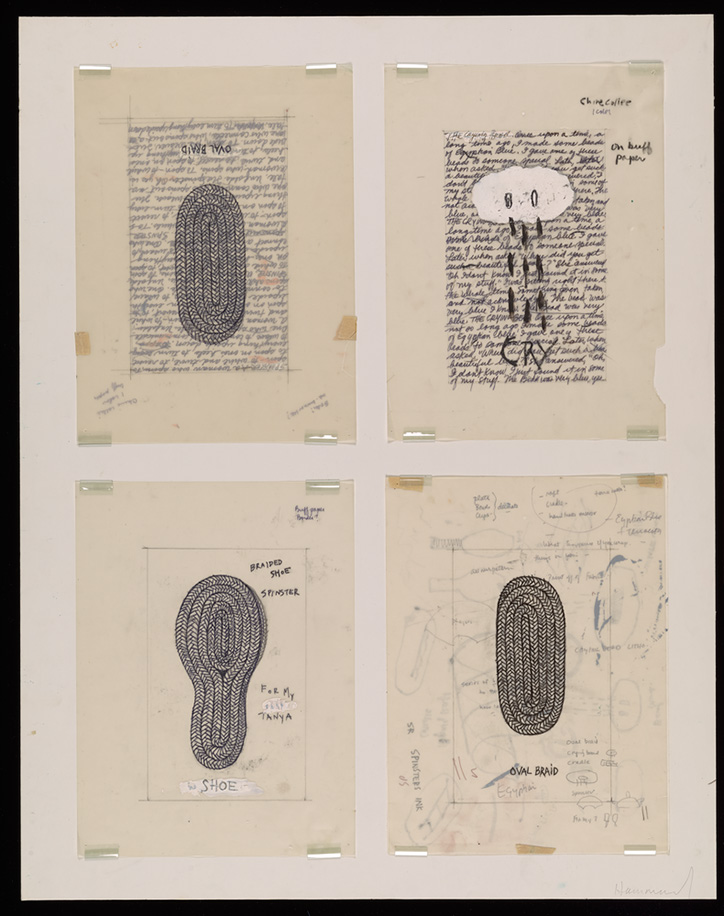

Studies for Shoe, Crying Bead, Oval Braid and Spinster Braid, 1978, Harmony Hammond. The Getty Research Institute, 2016.M.3. © Harmony Hammond

In 1973 the artist, curator, and scholar Harmony Hammond made a decisive change in her professional and personal life. “I came out as a lesbian artist,” she said, “meaning the two are connected and affect each other.” A pioneer of feminist, queer, and lesbian visual culture, Hammond has led a trailblazing career, creating art, curating exhibitions, publishing extensively, and cofounding a pioneering art collective and journal.

The Getty Research Institute recently acquired Hammond’s papers, adding a vast trove of materials specifically related to lesbian art to the Getty’s existing collections of modern and contemporary artists’ papers. The new papers shed light not only on Hammond’s work, but also on that of other artists and luminaries such as Kate Millett and Rita Mae Brown.

Featuring letters, essay drafts, newspaper clippings, photographs, rare ephemera, and more, the 35 boxes’ worth of materials trace the history of feminist and queer art from the 1970s to the 2000s.

Harmony the Artist

Hammond, born in 1944, has lived in Galisteo, New Mexico, since 1989, but she grew up in a suburb of Chicago, Illinois. She initially followed a conventional path, attending university and marrying at an early age. Following a move to New York City in 1970, Hammond divorced her husband, started practicing tai chi, and became involved with a women’s consciousness-raising group.

Two years later, Hammond joined with twenty other women to found A.I.R. (Artists in Residence), the first all-female, artist-run gallery in the United States. For a solo show at A.I.R. in 1973, her New York debut, Hammond expressed her “desire to break down the distinctions between painting and sculpture, between art and women’s work, and between art in craft and craft in art.”

The artist has used found, everyday materials such as rags, linoleum, straw, and latex in her artworks. Her sculptures, paintings, and prints are oftentimes abstract and always political, and have been featured in many groundbreaking exhibitions of lesbian/gay/queer/trans art.

Four of the 35 boxes in Hammond’s papers are dedicated to her artistic career and include photographs, gallery correspondence, and clippings of exhibition reviews. Hammond collected the source material for the imagery in her art, too, and these items fill another two boxes, along with several journals—featuring both writing and drawings—and agendas.

The collection also contains a complete set of Hammond’s graphic work and important early pieces, including the Hairbags (1972) that she made for members of her consciousness-raising group, and Shoe Poems (1977), as well as complete set of digital images of all her artworks, which will be made freely available to researchers.

Dance of the Ladder, 1981, Harmony Hammond. The Getty Research Institute, 2016.M.3. © Harmony Hammond

Harmony the Chronicler

Over the course of several decades, Hammond chronicled the development of queer and lesbian art history, and her papers meticulously record the personalities involved through documents, videos, DVDs, and slides. Five boxes are devoted solely to lesbian artists and are a who’s who of prominent figures from the late 20th century: Catherine Opie, Terry Wolverton, Dyke Action Machine, Ulrike Müller, and many more.

Throughout her teaching career at institutions like Sagaris and the University of Arizona, Hammond amassed several boxes worth of slides to use for research and in the classroom, and these are also part of the collection, along with her library of books. Hard-to-find publications, such as Redstockings and The Fox, are included. There are also several artists’ books, posters, and rare pieces of ephemera from Ida Applebroog, Suzanne Lacy, Zoe Leonard, and the LTTR collective, among others.

While documenting the pathbreakers in feminist and lesbian art, Hammond also corresponded with them. These meetings of great minds are represented in two boxes of correspondence with people such as Ana Mendieta, Adrienne Rich, and Faith Ringgold. There is a particularly high volume of letters from Lucy Lippard, Moira Roth, and Arlene Raven, all prominent scholars and critics.

Studies for Shoe, Crying Bead, Oval Braid and Spinster Braid, 1978, Harmony Hammond. The Getty Research Institute, 2016.M.3. © Harmony Hammond

Harmony the Scholar

As a scholar, Hammond has published several essays and books, most notably a groundbreaking text on the history of lesbian art since the 1970s, Lesbian Art in America: A Contemporary History (2000). She has also curated several landmark exhibitions, such as A Lesbian Show (1978) and Women of Sweetgrass, Cedar and Sage: Contemporary Art by Native American Women (1985).

In 1976, she cofounded the journal Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics, which ran for nearly two decades. Hammond’s papers feature a complete set of issues, along with drafts and documents related to Heresies, her published writing, and exhibitions.

While Hammond’s papers chart her diverse professional activities, there are some materials of a more personal nature, including items related to her role as a martial arts instructor and a box of private correspondence.

With the acquisition of the Harmony Hammond papers at the Getty Research Institute, researchers will have an unprecedented opportunity to delve into the history of feminist and lesbian/gay/queer/trans art through one of the pioneers of the field and the many fellow artists and scholars that came into her circle. The papers will be available for study once fully catalogued.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.