![Left: index card for Van Gogh's Iris [sic], $80,000, 4-30-47. Right: Irises](https://d3vjn2zm46gms2.cloudfront.net/blogs/2020/04/07142355/vangogh-composite_1600.jpg)

Left: Inventory cards, Sold alphabetical: Artists, 1907-1973, bulk 1907-1971, Box 160. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, (2012.M.54). Right: Irises, 1889, Vincent van Gogh. Oil on canvas, 29 1/4 × 37 1/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 90.PA.20

April 8, 2020 is the International Day of Provenance Research. Organized by the Arbeitskreis Provenienzforschung e.V., an international association of provenance researchers, the day is an opportunity to draw attention to the relevance of this discipline and highlight provenance work done by different institutions around the globe. Follow #TagderProvenienzforschung and #DayofProvenanceResearch on social media.

Tracing the biographies of artworks takes us on fascinating journeys. We learn about people, places and time. For the provenance researcher, these journeys include hours of detective work following clues spread across archives, libraries, museums and private homes all over the world. The increasing availability of digitized resources and online tools have made an impact on the work we do as a community to unravel the histories of artworks, from the moment of their creation until they reach their present locations, where we can enjoy them today.

To celebrate this year’s International Day of Provenance Research, we asked provenance teams across Getty to share some discoveries, resources, and tools that tell us what it means to do provenance research in this digital age.

— Sandra van Ginhoven, Head of the Project for the Study of Collecting and Provenance, Getty Research Institute

Comparing Clues: Discovering One Painting’s Nazi-Era History

Market Scene in an Imaginary Oriental Port, about 1764, Jean-Baptiste Pillement. Oil on canvas, 20 × 29 3/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003.20

The Getty acquired this scene of an imaginary foreign marketplace by Jean-Baptiste Pillement in 2003, and its provenance has only been traced as far back as 1911. Even tracking just one century of an object’s history can be challenging.

Previously it seemed that this painting stayed safely with its owner—a Belgian baron in France, Jean Germain Léon Cassel—during World War II, but we recently discovered that it had been confiscated by the Nazi regime.

Hundreds of thousands of artworks and personal possessions were illegally taken by the Nazi regime during the war. Today museums prioritize provenance research partly to ensure that they have not unknowingly acquired stolen goods. Restitution, or return, of possessions to their owners occurred shortly after the war and still continues to this day.

Because this painting was sold by Cassel’s estate in 1954, we had no reason to believe it had been confiscated during the war. However, markings on the back of the painting and material now available online have made it possible to confirm that it was, in fact, stolen by the Nazis and restituted by the Allies.

Verso of Market Scene in an Imaginary Oriental Port, about 1764, Jean-Baptiste Pillement. Oil on canvas, 20 × 29 3/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003.20

One number on the back, B3120, matches the Nazi inventory number found in their documents. From searching the ERR Project (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg) Jeu de Paume database, we learned that thousands of Cassel’s objects were confiscated in 1943, under the codename Action Bertha.

Another visible number, 9773, was assigned by the Allies at the Central Collecting Point, Munich, where recovered art was catalogued and sorted for restitution.

Central Collecting Point, Munich cataloging cards for Munich number 9773, Pillement’s Market Scene in an Imaginary Oriental Port (2003.20). Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Holocaust-Era Assets, https://www.fold3.com/image/312529146

From the National Archives’ documents digitized on Fold3 and the Deutsches Historisches Museum’s Database on the Central Collecting Point, Munich, we were able to find its cataloging card, which notes the painting’s recovery in an Austrian salt mine in 1945 and its shipment to Paris in May 1946.

Thanks to the increased accessibility and digitization of materials, we were able to compare the physical evidence on the painting and historic documents to determine where this painting traveled during World War II, and know that it did get returned to its owner.

— Nicole Block, Curatorial Assistant, Paintings, The J. Paul Getty Museum

Delving into Friendship and Family Genealogy: The Julia Margaret Cameron Overstone Album

The Overstone Album, 1864-65, Julia Margaret Cameron. Carved wooden cover of photographic album, approx. 12 x 10 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XZ.186

Spring, from the Overstone Album, May 1865, Julia Margaret Cameron. Albumen silver print, 10 x 8 ¾ in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XZ.186.42

The Overstone Album is a luxurious photographic volume made by Julia Margaret Cameron. It is filled with portraits of friends, family, and celebrities, as well as staged scenes inspired by literary and religious sources. Its wooden cover, with its intricately carved fern design, along with the 112 large-scale albumen prints, speak to Cameron’s ambitions for this album. She presented it with an inscription to her friend and patron, Lord Overstone (Samuel Jones Loyd), one of the wealthiest men in England, on August 5, 1865.

The Overstone Album, 1864–65, Julia Margaret Cameron. Front inside cover with inscription in ink by the artist, approx. 12 x 10 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XZ.186

Lord Overstone, negative made 1865, printed about 1870, Julia Margaret Cameron. 8 ¾ x 9 ½ in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 95.XM.54.3

The Overstone Album, Julia Margaret Cameron, front inside cover (detail). Full-page: approx. 12 x 10 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XZ.186

The album contains another trace of its subsequent ownership—a Lockinge bookplate (found just above the inscription). Lockinge is the name of the estate given by Lord Overstone to his daughter, Harriet, and her husband upon their marriage in 1858.

Through online genealogical research, we were able to create family trees for Harriet and her cousin, Arthur Thomas Loyd, to whom she left her estate. His descendants still run Lockinge Estate and, by matching auction records with the death dates of Loyd family members, we believe that the album remained in the family until it was sold at Sotheby’s in 1975.

We were able to fill in portions of the album’s past forty-five years by consulting auction catalogues and corresponding with auctioneers and gallerists who had sold the album. Each line of provenance from its 155-year life reveals friendships, family histories, the evolution of a vibrant market, and an aesthetic appreciation for photography.

— Carolyn Peter, Curatorial Assistant, Photographs, The J. Paul Getty Museum

Tracing Provenance in Digitized Catalogues

One of the small joys of provenance research is when familiar faces and names crop up unexpectedly, even years after you’ve first encountered them. I first ‘met’ Menekrates four and a half years ago while researching a large group purchase of antiquities by the Getty in 1971.

Grave Stele of Menekrates, about 150 B.C., east Greek. Marble, 21 5/8 × 12 × 2 3/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California, 71.AA.376

At the time, the provenance of this relief was relatively well-known. It had been part of the collection at Lowther Castle, formed in the mid 19th century, and it had remained there in northern England until 1969 when it, together with other ancient marbles, was sold at auction by the then-earl of Lonsdale. From the auction floor at Sotheby’s in London, the relief traveled to the Royal Athena Galleries in New York, and finally to Los Angeles.

The style and iconography of the relief suggest that it was made in the eastern part of the Greek world, perhaps in the area around Smyrna. But since William Lowther had collected ancient artworks over decades, largely from British collections formed a century or two prior, tracing his purchase and its earlier history presented a difficult puzzle.

Last year, while flipping through the virtual pages of an auction catalogue from 1755, I was surprised to see an entire page of Greek inscriptions, including Menekrates!

Title page of the Museum Meadianum, published by A. Langford, Covent Garden, London (1755).

Page 239 of the Museum Meadianum, published by A. Langford, Covent Garden, London (1755).

The catalogue itself is written entirely in Latin when it’s not quoting ancient authors in the original Greek. The tricky thing about this isn’t just working with catalogues close to 300 years old. For centuries, auction catalogues routinely didn’t include details about inscriptions like this at all. The English version of this same catalogue only lists the size (monumental), the number of figures (two), and the presence of an inscription. Without the Latin catalogue, we would have no way of identifying our relief.

In 1755, the relief was part of the sale of the estate of Dr. Richard Mead, who had served as the physician to British royalty, and whose extensive collections of rare books, gems, natural history specimens, and paintings took months to auction off following his death.

All three of the buyer annotations for the Greek inscriptions in Mead’s sale refer to a General Campbell, likely an alias used by another peer, the Duke of Argyll. One of the other three objects is now in the British Museum, but the last, with the Greek inscription beginning ZOSIMOS ASPASIAS has not yet been traced. Knowing that the Getty’s relief was with Richard Mead a century earlier suggests even further avenues of research into how and why antiquities like this were brought to England.

— Judith Barr, Curatorial Assistant, Antiquities, The J. Paul Getty Museum

The Getty Provenance Index® Gets an Update

Provenance work at the Getty goes far beyond the museum’s collection. The Getty Provenance Index® is a powerful online research tool produced by the team of the Project for the Study of Collecting and Provenance at the Getty Research Institute with many international collaborators. It contains transcriptions from different primary sources, collected since the 1980s, that can help trace the ownership of artworks. These include archival inventories, sales catalogs, and dealer stock books.

Formerly, each type of document was accessible through a separate interface. Since February, the Getty Provenance Index has been searchable through a unified interface, allowing researchers to find new connections that might have been hidden before.

Wisdom and Strength, about 1565, Paolo Veronese. Oil on canvas, 84 1/2 x 65 3/4 in. The Frick Collection, New York, 1912.1.128. Photo: Michael Bodycomb

Wisdom and Strength, painted by Italian artist Paolo Veronese in about 1565, and currently in the Frick Collection in New York, is an example of an artwork whose provenance can be traced through all three different types of primary sources included in the Getty Provenance Index. A simple search of the terms “Veronese” and “Wisdom” through the new unified search interface retrieves six records. The three that are highlighted concern the Frick painting:

Search results for “Veronese Wisdom” in the Getty Provenance Index®.

The first record is from one of the 13,000 archival inventories held in the Getty Provenance Index. An archival inventory is a list of paintings and other objects held in a private collection at a certain time. In this case, the record shows that Veronese’s painting was in the collection of Louis, Duke of Orléans, when it was inventoried in 1727.

The second highlighted record represents the 1798 sale of the painting in London, from one of the 22,000 sales catalogs indexed in our database. Louis’s grandson, Louis Philippe Joseph d’Orléans, sold his collection in 1791 in the midst of the French Revolution. After changing hands multiple times, the Italian paintings from the Orleans collection were exhibited for sale at the Lyceum Theater in London, starting in December 1798. A copy of the catalog, part of the Getty Research Institute’s Digital Collections, includes a drawing of the exhibition room:

The square numbered 223 (highlighted in red) represents Veronese’s Wisdom and Strength place in the exhibition. A catalogue of the Orleans’ Italian pictures, which will be exhibited for sale by private contract, on Wednesday, the 26th of December, 1798, and following days, at Mr. Bryan’s gallery, no. 88, Pall Mall, leaf 5 verso. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 880391. http://hdl.handle.net/10020/880391

Veronese’s Wisdom and Strength, number 223 in the catalog, was sold to the British collector Thomas Hope.

The last highlighted record tells us the painting’s journey to the United States. The firm M. Knoedler & Co, whose stock books make up over 40,300 records in the database, jointly owned the painting with British dealers P. & D. Colnaghi, Trotti & Co, and Thomas Agnew & Sons, and sold it in 1912 to Henry Clay Frick, who willed his house and all its contents as the Frick Collection upon his death in 1919.

The Getty Provenance Index allows immediate access to all these rich provenance sources and information through its newly updated search interface.

— Iñigo Salto-Santamaría, Graduate Intern, Project for the Study of Collecting and Provenance, Getty Research Institute

Tracking Down Van Gogh’s Irises: Finding Aids and Digitized Content

A strength of the Getty Library’s special collections is its dealer archives, which are comprised of more than 12,000 boxes and containers. These archives represent the business records of international art dealers and gallerists such as Duveen brothers, Goupil et. Cie. and M. Knoedler and Co. Dealer archives hold transactional data for selling works of art which may include inventories, stock books, consignment books, invoices, exhibition histories, joint acquisitions, photographs, and correspondence.

The M. Knoedler archive, and related dealer archives housed at the Getty Research Institute are vast and often interconnected. When some parts of these collections are transcribed and searchable, and other sections are not, how does the researcher successfully conduct their research?

Researchers might begin their research using the resources in the Getty Provenance Index ® with exacting results. As a next step, they might turn to the hundreds of selected boxes from the Knoedler archive which have so far been digitized and are also available for browsing online through the finding aid. Researchers can freely browse this digitized content and then work with Reference Librarians to fine-tune their research.

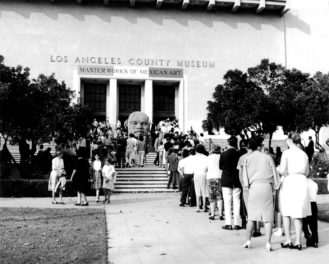

![Left: index card for Van Gogh's Iris [sic], $80,000, 4-30-47. Right: Irises](https://d3vjn2zm46gms2.cloudfront.net/blogs/2020/04/07142355/vangogh-composite_1600.jpg)

Left: Inventory cards, Sold alphabetical: Artists, 1907-1973, bulk 1907-1971, Box 160. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, (2012.M.54). Right: Irises, 1889, Vincent van Gogh. Oil on canvas, 29 1/4 × 37 1/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 90.PA.20

A search of the M. Knoedler Finding aid section for the artist files provides a result for van Gogh with the following data: box 2340, folder 10, there is a work by van Gogh titled (Iris) with the number CA2780. This is an important piece of information because it can lead to other parts of the collection including the inventory cards, consignment books, and sales books.

Tracking the number CA2780, a researcher can then locate the respective Consignment book by browsing the M. Knoedler finding aid to locate box 96 for Commission book 4:

Commission book 4 for 1943 January–1951 January. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, (CA2091-CA3809). (2012.M.54)

With this specific date information, April 1947, researchers can go to box 74 to Sales book 14.

Sales book 14 for April 1947, page 318 (CA2780), van Gogh, Iris. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, (2012.M.54).

Researchers are therefore able to track the sale of van Gogh’s Irises in the sales book, even if the painting did not appear at the beginning of their search in the transcribed stock books.

Getty continues to work across departments to connect data and resources: databases, finding aids, and digitized content. What may initially seem like a dead-end search may not be after all; when one persists with a deeper-dive into the related finding aids and close review of digitized content, the search may yield more information.

— Sally McKay, Head, Research Services, Getty Library, Getty Research Institute

Comments on this post are now closed.