Car Hood, Judy Chicago, 1964. Sprayed acrylic lacquer on Corvair car hood, 42 15/16 x 49 3/16 x 4 5/16 in. Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Acquired 2007 with means from The Second Museum of our Wishes. © Judy Chicago, 1964. Photo © Donald Woodman

In 1964, while a student in UCLA’s graduate program in painting and sculpture, artist Judy Chicago enrolled in auto-body school—the only woman in a class of 250 men. They were all there to learn how to custom-paint cars with candy-colored lacquer finishes and pinstriped detail work, hallmarks of the hot-rod car culture of Southern California in the 1960s.

Chicago’s Car Hood, featured in the exhibition Crosscurrents in L.A. Painting and Sculpture, 1950–1970, was her final project: an early ‘60s Chevrolet Corvair car hood sprayed with glossy acrylic lacquer. In her 1977 memoir, Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist, she described the gendered symbolism of Car Hood: “the vaginal form, penetrated by a phallic arrow, was mounted on the ‘masculine’ hood of a car, a very clear symbol of my state of mind at the time.”

Judy Chicago (then known by her married name, Judy Gerowitz) was an ambitious female artist trying to fit in with the male-dominated Ferus Gallery scene by “digging in” through “tough talk,” spray paint, and motorcycles. Among her colleagues, painter Billy Al Bengston borrowed spray-painting techniques from the world of motorcycle finishing (he was an avid racer), and John Chamberlain incorporated used car parts in his wall-mounted sculptures.

Despite her gender-crossing efforts, Chicago was met with blatant chauvinism. She was often told that a woman artist could not be taken seriously unless her work looked like it had been made by a man. This experience led her to question the ways women had been discouraged throughout history from expressing their own experiences, in art and all aspects of society. With other like-minded women artists, she went on to be a pioneering figure in the Feminist Art Movement that flourished in the 1970s. Chicago would create the Feminist Art Program at Cal State University Fresno (1970–71) and CalArts (1971–72), where female students engaged in consciousness-raising sessions and collaborative performances and installations that explored female experience.

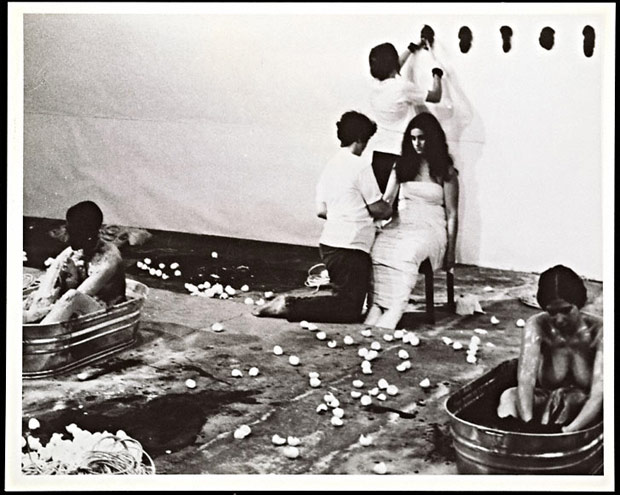

Ablutions performance at Guy Dill’s studio, with Judy Chicago, Suzanne Lacy, Sandra Orgel, and Aviva Rahmani (Sponsored by Feminist Art Program at CalArts), 1972. The Getty Research Institute, Gift of Art in the Public Interest and 18th Street Arts Center, 2006.M.8.42. Photo courtesy Lloyd Hamrol. On view in Greetings from L.A.: Artists and Publics, 1950–1980 at the Getty Research Institute.

Is it still a man’s world for artists working today?

The statistics are damning—while approximately half the graduates of art programs are women, there is still a glass ceiling for women artists. According to recent statistics from the National Endowment for the Arts, women artists earn about 75¢ for every dollar male artists earn, despite having more schooling on average than their male peers. And older women fare even worse: once they hit 55, they earn only 60¢ on the dollar.

Who is taking up the mantle of feminism in today’s art world? Since 1985, feminist activist group the Guerrilla Girls have graphically articulated gender (and racial) inequality in the art world through their posters and actions. The Guerrilla Girls’ records from 1979 to 2003 now reside in the special collections of the Getty Research Institute, but the group is still going strong around the world—as are other feminist artists, including Chicago herself.

While we’ve come a long way since the 1960s, when Judy Chicago was told that she couldn’t be a woman and an artist, this Guerrilla Girls’ poster—created in 1988 but still relevant today—reminds us of the oft-invisible struggle of women artists.

What do you think? Is the art world still a man’s world, or is chauvinism a thing of the past?

Question of the Week is a series inspired by our Masterpiece of the Week tours. Featuring an open and upbeat discussion among visitors and gallery teachers, the tours feature a new object and pose a new question each week. Chicago’s Car Hood is the object for December 6–11, 2011.

Times have changed, and more and more women artists are finding opportunities to have their work shown and valued. But the concept of the premium, genius, top-tier artist is still very much a male one. If Jeff Koons were a woman (just imagine it for a moment — somehow, it seems impossible), would her sculptures sell for $23 million?

I think most of the women artists that we hear about unfortunately have realized that the only way to be recognized or paid any mind to as a Woman Artist™ is to find a reason to take your shirt off, no matter how stupid or flimsy it might be. When you get right down to it, if a woman’s art isn’t categorizable somehow as porno, no one cares what she has to say. If she wants to make art about her genitals, she’ll be tolerated although still ghettoized. If she wants to talk about 14th century French poetry, the black death, Mexican independence, or anything that’s not porno, she’d better find a way to connect it to taking her clothes off … and she’ll still get ghettoized for it. (And no one will listen to what she has to say anyway, because they’re too busy jerking off.)

Cynical? I’d call it a blunt statement of reality, which often annoys people, including “radicals” who are supposed to be into kicking the beehive with blunt expressions of reality but who don’t want their own beehive kicked.

Women still have to juggle life and are not free to develop an art career. If they choose to try to “have it all” and return from child-rearing as an older artist with seriousness, the opportunities are still limited unless their ideas and methods are contemporary and/or timeless.

Let’s see, there are emerging artists, mid career artists and? So it boils down to a twofold problem; the singular focus an artist needs and a supportive society.

I don’t see where much has changed.

Yes, I agree that women still have to “juggle” life and art careers (and I don’t think that is going to change anytime soon) so, What do we do? Do we sacrifice one for the other? Do we settle for part- time motherhood and part time art making? Do we put it aside to pick it up 20 years later after children go to college?

I wonder how men feel about this?

A supportive society is imperative to meet the challenges that women artists face wanting a career and a family…

Who changes society if not mothers raising children? We can start with our own boys, teaching them that we are not only mothers and wives, but also artists.

Thank you Anna, Janis, Beth, and Laura for your thoughtful responses.

In her essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” (originally published in the January 1971 issue of ARTNews), feminist art historian Linda Nochlin writes:

“The question “Why have there been no great women artists?” has led us to the conclusion, so far, that art is not a free, autonomous activity of a super-endowed individual, “influenced” by previous artists, and, more vaguely and superficially, by “social forces,” but rather, that the total situation of art making, both in terms of the development of the art maker and in the nature and quality of the work of art itself, occur in a social situation, are integral elements of this social structure, and are mediated and determined by specific and definable social institutions, be they art academies, systems of patronage, mythologies of the divine creator, artist as he-man or social outcast.”

That is, inequality is systemic, written into the design of our social structures–art history included.

One of the reasons why feminist art holds resonance is that it brings the subject of lived experience into the formal and aesthetic realm. However, this emphasis on personal experience may be (and in fact, was intended to be) antithetical to the values of the art market and art institutions at large. So the question faced by Judy Chicago in the 1960s, and by artists working today, remains: Do you change your work to fit existing (perhaps sexist) structures, work to change the institutions of art, or create alternate models? While these changes should be made by the leadership of museums, galleries, and individual collectors, they also need take place within art schools (where young artists are socialized and mentored), in the artistic community, and at home. I agree with Laura that if gender equality and opportunity are to flourish, the cause needs to also be taken up by men, and not just by women alone.

Even once they have gained access to the art world, artists working today–particularly non-white and non-male–face the dilemma of whether they want to be identified as such, or whether they can be known as an “artist” without cultural or gendered qualifications. I remember an interesting classroom conversation from art school, in which I wondered that if we commonly use terms like “black woman artist” or “outsider artist,” why don’t we also feel inclined to call someone a “white male insider artist”? Of course, doing so would reveal the implicit bias in the way we use language in society.

In addition to gauging the achievement of women artists through such markers as auction prices and blockbuster exhibitions, I think it is equally important for male and female artists to have access the works of women artists of the past and to publicly acknowledge these influences in order to establish that these lineages and traditions belong within the canon of art history.

Yes, why not rewrite history–it’s done every day. Let’s go on a quest to unearth the unsung women artists like Camille Claudel (Rodin’s Asst?) and others who had the courage and passion to pursue their art outside society’s confines. Acknowledging, and unfortunately even finding, their work is long overdue.