Meet Bryan. He’s assistant curator of manuscripts at the Getty Museum, an adjunct art history professor, an indefatigable blogger, and an all-around dynamo with a most excellent collection of scarves and bow ties.

Bryan set aside last Tuesday morning for an Instagram Q&A on the occasion of his new exhibition, Traversing the Globe through Illuminated Manuscripts, which has been almost a decade in the making, from first spark of idea to final fruition. The Q&A got interesting right quick thanks to your awesome questions, which ranged from career advice to book reviews, so we’re putting them on his permanent record right here.

And look for more Q&As coming up over on @gettymuseum Instagram. Thanks to everyone who participated.

On Cross-Cultural Exchange in the Middle Ages

Hey Bryan! A few terms ago I wrote a paper on illuminated manuscripts from the crusades, specifically the Maqamat al-Hariri. One of the main theories was that Byzantine illumination influenced Muslim book painting, but I feel this theory lacks something…What is your opinion on this? —@rururupert

I would read cover-to-cover the Met’s catalogue for Byzantium and Islam. Amazing exhibition and great up-to-date bibliography on these types of questions. “Influence” is always a heavily weighted word that often suggests a one-way relationship between two disparate things, when in reality a two-way, mutual exchange (between interwoven phenomena) is more likely the case. For al-Hariri’s Maqamat (12th century), we might also explore linguistic imitation in other Arabic, Hebrew, and Andalucian examples.

What kind of people would have traveled in the Middle Ages? And how would travel have affected the lives of ordinary people who didn’t? —@erinmayyyy

The Cluny (Paris) and Bargello (Florence) just did a great exhibition on this exact topic! Pilgrims, soldiers, diplomats, and merchants primarily would have traveled, but also royals and religious figures, from popes to priests to missionaries of all faiths. The Getty exhibition features several images of travelers (including pilgrim-saint James the Greater and embassies during the Hundred Years’ War). People who didn’t travel certainly benefitted from the import of organic goods, such as plants and spices, and from luxury items that were traded—even if they just got to see them but never actually own them.

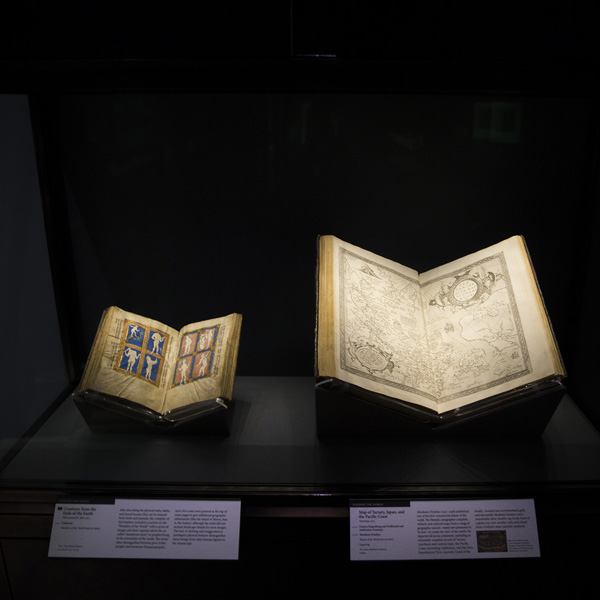

Installation view of Traversing the Globe through Illuminated Manuscripts

Bryan, how is discrimination evident in manuscripts? Blatantly? Not at all? —@emiliaguth

We have to be careful when defining discrimination or racism or prejudice in the Middle Ages; careful, that is, not to cast our own ideas about what constitutes discrimination. There were certainly beliefs of superiority and inferiority—our Spanish legal manuscript privileges Christians over Jews or Muslims, for example—and the concept of “otherness” is a long-standing field that inquires how minorities or foreigners have been represented in the visual arts, globally.

What evidence can you glean of cross-cultural exchange from the period’s ceramics and textiles? —@angelicahosn

In the exhibition we show how dragons and phoenixes in Chinese art inspired ceramics and textiles in Persia and Armenia, and into Europe. And we also see ceramics and textiles represented in manuscripts; sometimes silk veils were sewn into manuscripts to protect them and add a layer of sanctity.

Are there any common misconceptions about the Middle Ages that came about because of interpretations of illuminated manuscripts—either due to misinterpretation of the meaning or scope of those manuscripts? —@ratesofgrowth

We see plenty of dragons, knights, castles, unicorns, and pointy hats in manuscripts. These images certainly contribute to our popular ideas about the Middle Ages (from Disney to Game of Thrones). We sometimes assume that the entire +/-thousand-year period of the Middle Ages in Europe were like Monty Python’s Holy Grail, and that everyone was basically illiterate and Christian (or not), and that death was everywhere. We’ve organized exhibitions at the Getty that touch on these ideas and more specifically about what was possible within the medieval imagination. One dream of mine is to do an exhibition that juxtaposes medieval manuscripts with graphic novels/comic books. So many connections! (And I’m a mega comic book fan and erstwhile collector.)

On Pigments, Unicorns, and Bathtubs

Were illuminated manuscripts commissioned with specific content guidelines, or was the artist able to exercise a degree of free rein? Who was the typical owner? —@daemonsdomain

Manuscripts, like other works of art, often involved close communication between the patron and the artist(s). Books of hours, for example, could be highly personalized objects—everything from which prayers, saints, materials, etc., to include. But there was also a market for essentially ready-made prayer books that a middle-class patron could buy on the open market, and then customize according to one’s means. In the exhibition we have books made for high-ranking religious figures, middle-class merchants, men and women, young and old, from India to Italy, and from Poland to Peru.

Where can I find more info about pigments that were used? —@conclapo

Visit Yale’s Traveling Scriptorium. Super-beautiful and useful resource. I teach from their site all the time! The Getty YouTube channel also has great manuscript resources.

Do you have a favorite illuminated manuscript? A top 5? Which ones and why? —@bamitsbhutani

Fave manuscripts (in no order): the Great Mongol Shahnama, anything by Giulio Clovio, and any book that traveled across great distances historically (like the Shah Abbas Bible).

I read that Christian monks would recycle old manuscripts and that it’s sometimes possible to image these “deleted” works. I’m thinking of the Archimedes Palimpsest as an example. Did other cultures repurpose manuscripts deemed “disposable” as well? —@kalekalekalekalekale

Many palimpsest manuscripts (books with layered/rewritten writing) exist. We have some beautifully edited manuscripts, some with evidence of medieval scraping and others that were handsomely copyedited.

Detail from a Decorated Canceled Page in the Abbey Bible, about 1250–62. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 107, fol. 96v

Manuscript recycling wasn’t limited to Europe—one great example of the “recycling” of books is the so-called Cairo Geniza. Google it. Super-fascinating story. Also, there are great stories of Egyptian mummies that were wrapped in papyrus fragments.

I loved People of the Book by Geraldine Brooks. Did you? —@emiliaguth

The Sarajevo Haggadah is an extraordinary manuscript that has lived an extraordinary life, and the tale she wove is absolutely fascinating! I should add this manuscript to my list of favorite books that have traveled impressive distances!

Are there unicorns in manuscripts outside of Europe? What about other mythical horselike animals? —@poppersthepony

Unicorn, qilin, or rhino… same word, different cultures, from the ancient to the medieval worlds to China and the Islamic world. People have been fascinated by these one-horned creatures for ages. And don’t get me started on narwhals!

What were hygiene customs and plumbing like in the Middle Ages? —@letthemeatcake9

Plumbing existed in some parts of the world, even in Roman times. My favorite bathtub scene involves Saint Nicholas reviving three boys who were pickled in a tub.

Voynich: real or fake?

Dealer confection or mysterious 15th-century herbal/cosmographic text? Scholars in numerous fields have weighed in, citing historical antecedents for such a book, secret societies, and carbon dating to prove/disprove the manuscript’s authenticity. I’ve never beheld the manuscript in person, so the jury’s out!

On Being (and Becoming) a Curator

What is the most astonishing discovery you have made as a Getty curator? —@inglewood89

Rediscovering a set of choir books that were lost for decades. The story involved an eccentric priest who was preserving the books in his private cell. When I found them, he sang from the books for over 8 hours. It was pretty epic and moving.

How much do you familiarize yourself with the manuscript holdings of other institutions? How frequently/extensively do you draw on manuscripts outside the Getty’s collection for special exhibitions? —@therealnancyo

I must say that’s one of my favorite things to do. At least once a quarter, I try to look at other manuscripts in local collections (libraries, museums, archives, private collections). And every trip I take for work involves looking at manuscripts. The current exhibition has about 80 objects, a little more than a third of which are on loan from local collections in Los Angeles.

How does your team decide how to arrange the curated works in your exhibition halls? —@rachaellawriter

It’s a team effort that involves education, conservation, design, curatorial, and the preparation team. The safety of the object is most important, ensuring that all visitors can look comfortably at the illuminations, making sure that every work of art is presented in the best low-light level as possible, and that the theme comes across clearly for all audiences (from newbies to scholars to my own grandparents!).

Installation view of Traversing the Globe through Illuminated Manuscripts

Considering that you are curating (mostly) ancient documents, do you feel a certain responsibility of having the definitive word on what or how something was/used to be? (As a modern audience, we have to completely trust your word on how things were, versus with contemporary art as an evolving continuum among the audience’s known culture as a context, there’s no way to have a definitive/final say when the audience can judge/question more for itself.) Does that make sense…? Thanks! —@daphneplease

Yes. For this exhibition, I had a number of informal focus groups with students at all levels, colleagues in different departments, and colleagues beyond the Museum before beginning to write any of the texts for the show. I also read broadly in fields beyond my own and looked to anthropology, political history, sociology, and even medicinal history to try to make sure that the exhibition presents a range of ideas. Some of the more difficult themes to address with historical accuracy and contemporary sensitivity related to religion, race, and military conflict.

How should art students start their career in curating? —@yanawaltz

- Study art history.

- Find a passion.

- Visit as many museums as you can (not just art museums), and also look at their websites for digital collections and social media initiatives on all platforms.

- Pay attention to the display, collecting, and conservation histories of objects.

- Somewhere along the way, it always helps to learn languages and to learn to make art.

One of the best things I ever did was take a class on tempera painting (an egg-based medium) and another on marble carving. Really gets you into the mind of the artist!

How did you start off once you became a curator? Things you did to further your education, places you worked, and how long it took you to get where you are now?…. Do you see yourself going anywhere else as a curator? —@vivi_bibirona

I started as an educator, actually! Then I pursued graduate degrees to become a curator. It has taken about 10 years to reach this point.

As for going somewhere else? Well, there are three institutions in the U.S. that exhibit their manuscripts collections regularly: the Getty, the Morgan Library in New York, and the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. Of course Cleveland, the Met, the National Gallery of Art in D.C., and many others have amazing manuscripts collections. Not to mention the many great libraries and collections in Europe, and the private collections from Australia to Qatar. Manuscripts are of course paintings in books, and I do enjoy working across mediums and supports (parchment or panel). But the Getty is an amazing place where a job is actually a dream!

I’m considering majoring in art history with the goal of becoming a curator at an art museum. I have a few questions that I would love to have answered. First of all, what level of education would be ideal for this career path and would it be beneficial to narrow my focus of study, i.e., region, time period, or style? Also, would a second major in international studies be a good match to art history? Finally, as a curator, are you able to be involved in the design of exhibits and advertising them to the public? I visited the Getty recently for the first time, and I have to say it was a great experience! Thanks for taking the time to answer questions. —@benelliott98

Curatorial work requires many skills, including a background in art history (the broader the better, but also with an area of focus), languages (the more the better), and even digital savvy.

There’s no one path: Some have PhDs, some don’t. Some work across materials/media, others focus on a single type of object. More and more, global or cross-cultural and material studies are important, as are expanding our knowledge about an object’s use or historical approaches to race, gender, sexuality, and other topics that are relevant today.

What an entertaining exchange! I enjoyed the questions and replies. Illuminated manuscripts have always intrigued me and reading this post has encouraged me to visit the Getty and this exhibit. Many thanks, Darcanne