Initial D: Saint John the Baptist, about 1520, Matteo da Milano. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 87, fol. 4

Turning the pages of the illuminated manuscripts is an awe-inspiring experience, not only because of the glint of radiant gold, but also because of the painted depictions of precious stones, gems, cameos, pearls, and coral that often fill their borders and letters. Artists, collectors, and thinkers have been fascinated by these shiny objects for centuries—from the Middle Ages through Victorian times to today.

Harnessing the Powers of Gems in Medieval Manuscripts

One of our favorite depictions of precious stones in a manuscript is this one found in a large gradual (a book containing the sung portions of the Mass).

Initial R: The Resurrection, late 15th or early 16th century, Antonio da Monza. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig VI 3, fol. 16

Festoons of flowers drip with fictive sapphires, emeralds, pearls, and ancient cameos carved from naturally layered stone (the cameo at top center represents a reclining couple, for example). Still more gems are suspended from the wings of fantastic creatures, tendrils of foliage, and the hooves of winged-satyrs. At the top of the initial R containing a scene of the resurrected Christ, illuminator Antonio da Monza explored the iridescence of opal, while in the vertical descender of the letter he simulated a rock crystal reliquary containing the martyr-saint Sebastian from the 3rd century A.D. The palette of the entire page can be described as nothing short of jewel-like.

For medieval and Renaissance viewers of manuscripts and wearers of jewelry, precious stones were not only beautiful. Worn correctly, gems were thought to harness “virtues” or powers to protect their owners from harm. It’s no surprise, then, that the multi-hued brooch-like interlace designs found in a twelfth-century service book from Montecassino, Italy, entrap wild dogs and demon-like faces. The reader-viewer would have found protection from distraction and temptation through these painted talismans.

The power of gems was suggested early on in ancient Babylon (present-day Iraq), when the colors of stones were associated with the hues of planets and distant stars. To this notion, the ancient Greeks added ideas about medicinal properties connected with gems. While it may seem superstitious to some today, these views were widely entertained and hotly debated by well-educated members of the medieval clergy, including Albertus Magnus (St. Albert of Cologne) and Saint Thomas Aquinas.

Woodblock printed frontispiece of a 1502 edition of Liber Secretorum Alberti Magni, reproduced from The Book of Secrets of Albertus Magnus edited by Michael R. Best and Frank Brightman (York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, 1999)

In his Book of Secrets, written in the late thirteenth century, Albertus Magnus suggested wearing diamonds on the left side of the body to protect against a wide array of terrors including madness, wild beasts, and venom. He wrote that the sapphire would protect the body and keep its parts and limbs unbroken. But be careful: it also cools the fires of passion and leaves its wearer “entirely chaste.” Perhaps the most succinct position on jewels in the Middle Ages is English theologian Alexander Neckam’s description of gems as having “wondrous power, sparkling light, elegant beauty” (paraphrased from a lengthy text on the natural world).

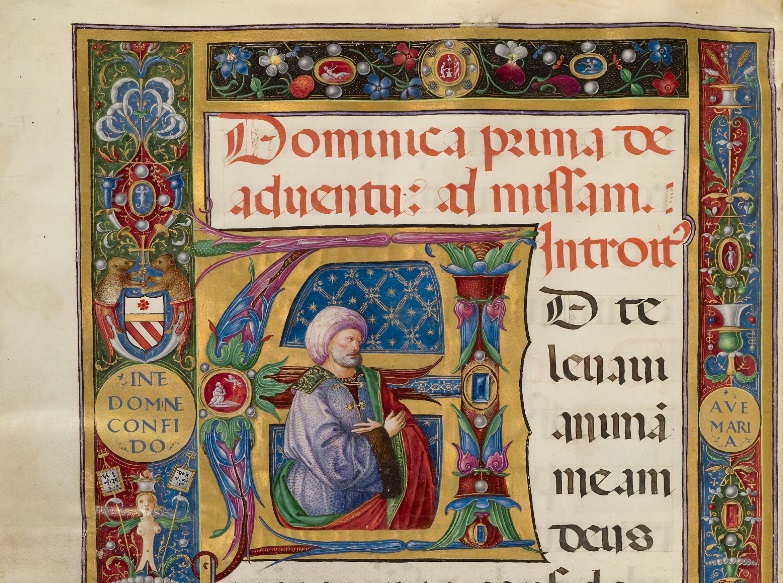

We often find gems in manuscripts dedicated to use in the church or for personal devotion. This missal (containing texts used during Mass) illuminated by Matteo da Milano is replete with rubies and packed with pearls.

Don’t miss the bear cubs, representing the Orsini (Italian for “Little Bears”) family, patiently holding up a gold cross. Initial A: King David, about 1520, Matteo da Milano. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 87, fol. 52v

The connection between liturgical manuscripts (books used in church services) and the representation of precious stones may stem from the belief that gems originated in the four rivers of Paradise before the fall of humankind. In a fifteenth-century compendium of world history, we catch a fleeting glimpse of these stones flowing out of Eden in the lower right corner of the river, as an angel seals the entrance to Paradise with a flaming sword and wall of fire.

The Angel of Paradise with a Sword in Mirror of History, about 1475. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIII 5, vol. 1, fol. 54v

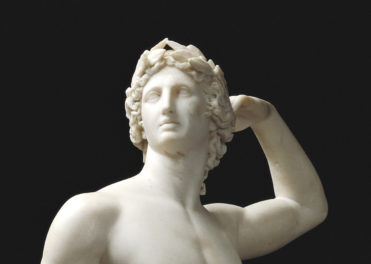

Precious stones also found their way into church ritual through integration in Eucharistic monstrances, reliquaries, and the rings and copes of the clergy, such as the massive morse (clasp) worn by Pope Paul V in this portrait bust sculpted by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Bust of Pope Paul V, 1621, Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Marble. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s

While the sheer number of precious stones in illuminated manuscripts is impressive, true luxury lovers will notice the repetition of only a small variety of gems. Rubies, emeralds, sapphires, and diamonds represent the most common gems used during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini, following ancient and medieval precedents, associated the ruby with fire, the sapphire with air, the emerald with earth, and the diamond with water, and considered all other stones to be simply variations of these four elements.

Victorian Symbolism

Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née Thérèse Feuillant (detail), 1866, James Tissot. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007.7

Art enthusiasts and collectors in the Victorian era were drawn to scenes of everyday life. In the 19th century, every “thing” had an indirect meaning. The culture was driven by symbolism, and every mislaid glove or overturned inkwell was evidence of a scandalous affair or a broken home. Whether it is the language of flowers or the vocabulary of a properly decorated parlor room, Victorians had a proverbial handbook for decoding every nuanced aspect of their lives.

It should come as no surprise, then, that jewels spoke volumes about a particular person’s station in life. Through a glittering jet necklace, one communicated a recent death in the family or religious piety. This second meaning is depicted in Tissot’s portrait of the Marquise de Miramon shown above. (Notice also the symbolically draped glove on the fireplace mantle.)

Wearing Etruscan Revival jewelry from the firm of Castellani in Rome meant the proper souvenir had been obtained on one’s Grand Tour, and one could be dubbed a scholar of the world. Pieces of jewelry encapsulated moments in people’s lives and broadcasted the truths of their experience to the rest of the world.

One of a Pair of Disk Earrings, Etruscan, 6th century B.C. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.AM.2

The Victorian obsession with “thingness” actually has a lot to do with medieval and Renaissance ideas about jewels, bodily adornment, and religious symbolism. The vast array of symbols associated with Christian art is at the core of many Victorian traditions. Mourning jewelry resembles early reliquaries, and nearly every decorative motif can be tied to the Virgin Mary or to Christ. A nineteenth-century painted Essex crystal brooch with images of goldfinches and thistles isn’t merely a scene of wildlife, but an evocation of the Passion of Christ (an association made since the Middle Ages).

Holy Family, 1872, Julia Margaret Cameron. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.443.19

Victorian artists, writers, and thinkers turned to medieval motifs found in manuscripts and material culture to harken back to a time thought to be more pious. To some, the Middle Ages were a golden moment when painters approached their art with a meticulous precision for natural details. In The Ransom by Pre-Raphaelite artist John Everett Millais, the central protagonist knight embraces his daughters with one arm while extending the other to present kidnappers with jewels of pearls and gold. English photographer Julia Margaret Cameron staged a Renaissance-like tableau vivant of the Holy Family using local children and her maid, who wears a stunning necklace of pearls and granulated gold shaped as the Star of David.

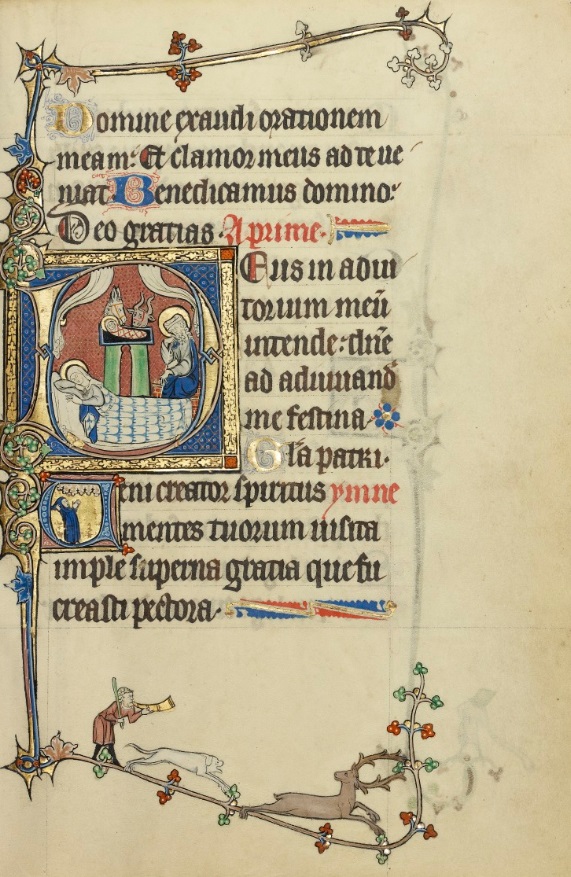

Initial D: The Nativity in the Ruskin Hours, about 1300. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 3, fol. 76

Victorian art critic and author John Ruskin wrote extensively about his own personal fourteenth-century French Gothic book of hours (prayers for private devotion), now known as the Ruskin Hours. In his text he provided traced designs that influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and helped spread an appreciation for medieval culture in the 19th century.

In the page shown above, the red and blue diaper patterns behind the manger scene and the initial D would have appealed to Ruskin’s sentiments about the glory of the Gothic page. William Morris, an artist well known for his textile and wallpaper designs, owned several medieval manuscripts including this New Testament, created in France around 1170 and now in the Getty’s collection. It’s tempting to make links between Morris’s patterns and those found in the Getty manuscript. We can also draw links between motifs found in medieval art and the art nouveau style of English artist and illustrator Pickford Waller, known for his wallpaper designs and illustrations for Grimms’ Fairy Tales, among others.

Canon Table Page in a New Testament (with Canons of Priscillian), about 1170. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig I 4, fol. 16v

Reading medieval and Renaissance symbolism through the lens of Victorian “thingness” can get very heavy, and may seem far from our own contemporary life. One stepping stone from the Victorian era to today is the work The Curious Lore of Precious Stones written in 1913 (and available online) by George Frederick Kunz. A mineralogist and gemstone collector, Kunz was a very important personality at Tiffany & Co. around the turn of the century. Born in 1856, Kunz was most definitely a child of the Victorian age, and wrote many books similar in tone to Albertus Magnus’s Book of Secrets. His texts detailed for people of the 20th century what each gemstone was purported to achieve, or the attributes it could bring forward in the person who wore it. Only 100 years ago, readers were intensely interested in the theatrical aspects of the legends and history in Kunz’s book, such as the ancient idea that amethyst could keep drunkenness at bay.

21st-Century Statement Jewelry

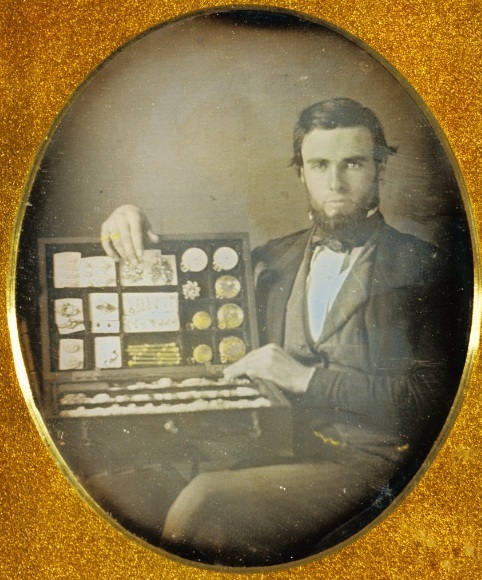

Jumping forward to today, while we in 2015 may not view an orchid placed on the mantelpiece as clear evidence of infidelity, we have certainly been taught to “read” jewelry through brand recognition. The nineteenth-century penchant for advertising one’s status and profession through photography, a process that requires sophisticated knowledge of how precious metals react to light and liquids, resonates in lasting ways.

Portrait of a Jewelry Salesman, 1853–54, attributed to Robert h. Vance. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XT.1565.18

In the 21st century, savvy jewelers strive to create an aura around their brand that immediately identifies the sort of individual wearing the jewelry. Pamela Love, a New York jeweler, relies heavily on the New Age, Bohemian aesthetic to sell her creations. Her work is replete with pyramids, eyes, pentagrams, spiders, triangles, malachite, lapis, crystal, and turquoise. She’s not only selling jewelry that celebrates its lineage—based in pseudo-pagan, mystic and spiritual symbolism—but also an idealized “vibe” of what it means to be a modern Brooklynite.

Master jewelers like JAR (Joel Arthur Rosenthal) and Taffin and Hemmerle have capitalized on creating ultra-exclusive jewelry for the elite. The use of unexpected materials—like milky diamonds that fluoresce, usually thought of as a negative quality—emphasizes color and design above clarity. Taffin and Hemmerle use string, corroded iron, copper, wood, and other unusual materials that pair with gemstones to create unexpected color contrasts. An aura of exclusivity and quasi-mysticism prevails in their almost impenetrable jewelbox boutiques; in fact, you must be invited to become a JAR client.

Jewelry is the ultimate decorative art, and gems have always been symbols and sources of power. A piece of jewelry can serve as a talisman or as an emblem of all that the wearer stands for or embodies. The concept of “statement jewelry” would make perfect sense to a person of the Middle Ages or the Victorian era. Like it or not, most of us classify others based on what they wear and how they adorn themselves. This tendency to “read” precious objects and their owners goes back millennia.

Louis XII of France Kneeling in Prayer, Accompanied by Saints Michael, Charlemagne Louis, and Denis (detail) in The Hours of Louis XII, 1498/99, Jean Bourdichon. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 79a, recto

Comments on this post are now closed.