The miraculous tales told in the luminous stained glass of Canterbury’s Trinity Chapel began with a martyr.

St. Thomas Becket Window (detail), made in 1919 from fragments of 13th-century glass, Canterbury Cathedral. Photo: TTaylor via Wikimedia Commons

On a wintry December evening in 1170, four knights, believing they were carrying out King Henry II’s will to rid the kingdom of a “low-born clerk” who defied royal authority, brutally murdered Archbishop Thomas Becket inside Canterbury Cathedral. Soon after, accounts of miraculous healing spread. The martyr Becket became revered by Christians across Europe, from ordinary townsfolk to the King of France. Like the pilgrims of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, countless thousands traveled from near and far to Canterbury to visit his tomb—each with a story, each believing the deceased archbishop could cure a variety of infirmities. In the year after his death alone, there were an estimated 100,000 visitors.

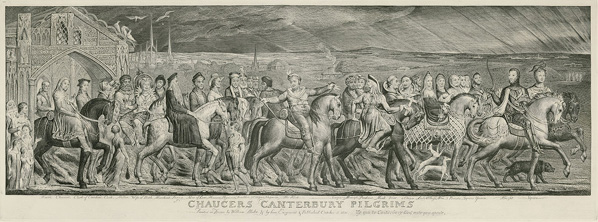

The Canterbury Pilgrims, William Blake, 1810. Artwork and photo: The McCormick Library of Special Collections at Northwestern University, Illinois, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1174, just a few years after Becket’s martyrdom and swift canonization as St. Thomas, a great fire destroyed much of Canterbury Cathedral, prompting a massive rebuilding, as well as the creation of three sets of stunning stained glass windows—including the luminous “Miracle Windows” that depict miracles believed to be wrought by the saint. The windows were meant to inspire reverence for Becket. Jeffrey Weaver, co-curator of the exhibition Canterbury and St. Albans, explains that the stained glass reveals the importance of images in devotion “not just as decoration, but as vehicles for furthering spiritual lives.”

As St. Thomas’s fame grew, his bones were moved to an opulent shrine faced with gold, studded with precious gems, and elevated in the middle of the Cathedral’s Trinity Chapel, amplifying the importance of his cult. As Dr. Robert Willis, Dean of Canterbury, describes, pilgrims would “enter into another world,” walking around the golden shrine in a “jewel box of stained glass.” Surrounded by colorful images of Becket’s miracles in the radiant windows, the faithful sought blessings in a transcendent environment. The phenomenon of the “cult of Becket” had proved to be a spiritual and economic boon that benefited the neighboring community and helped to finance the expansion of the Cathedral. Some pilgrims would bestow gifts, and many left with souvenirs of metal pilgrim badges and vials of holy water tinged with the spilled blood of the archbishop.

Every Picture Tells a Story

The Miracle Windows at Canterbury—made soon after the Ancestors of Christ windows, six of which are on display at the Getty—portray some of the over 700 miracles attributed to Thomas Becket after his murder, and documented by two monks, Benedict of Peterborough and William of Canterbury.

St. Thomas Becket Window, Becket at altar (detail), Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral. Photo: TTaylor via Wikimedia Commons

One of the first windows in the ambulatory of Trinity Chapel focuses on Becket; other windows tell the stories of individuals who experienced healing through prayer, drinking Becket’s holy water, and/or visiting his tomb with their maladies and disabilities—everything from leprosy and dropsy to blindness, paralysis, and even death! In the Middle Ages, illness was often believed to be punishment from God, and seeking intercession from a saint seemed a logical move. Indeed, there was strong incentive to seek the mercies of a saint, since a miraculous cure would be preferable to alternative treatments of the day, such as leeching, trepanation (drilling a hole in the head), or surgery by the local barber.

While memorializing St. Thomas Becket, the Miracle Windows picture “before-and-after” events as if scenes from a film’s storyboard, detailing the trials and salvation of individuals, both ordinary and prominent. Pilgrims would see people like themselves, such as Adam, Ethelreda, Henry, and Hugh, in the luminous painted glass.

The Arrow and the Forester

In the south ambulatory, we see the story of Adam the Forester, as told to William of Canterbury, and set in four medallions, or roundels. In the first scene below, Adam (far left) is shot in the neck by an arrow from the bow of a desperate poacher. The forester’s job was to protect the king’s forest from poachers—and the penalty for poaching was death. Another poacher (far right) absconds with a deer thrown over his shoulder.

Adam the Forester, south ambulatory window (detail), Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral. Photo: Anne-Marie Boucher CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Following scenes in the set depict Adam in bed surrounded by friends in the king’s castle. He drinks Canterbury water containing the blood of the saint, and lo and behold, his lethal piercing is miraculously healed. In a concluding roundel, Adam offers thanks at Becket’s tomb.

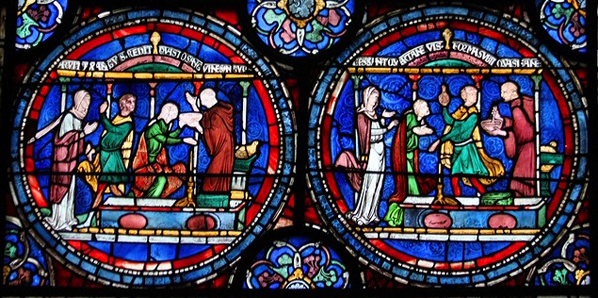

The Fever of Ethelreda

Moving to the windows in the north ambulatory, the ancient malarial disease known as Quartan fever, reoccurring every fourth day, has stricken Ethelreda of Canterbury. The Latin inscription above the scene implies that she is pale from the loss of red blood. At the tomb, she sips the blood of St. Thomas diluted with water from a bowl.

Ethelreda, north ambulatory window (detail), Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral. Photo: Anne-Marie Boucher CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Miraculously, in the second roundel, she is cured and offering her gratitude to the martyred archbishop.

Ethelreda, north ambulatory window (detail), Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral. Photo: Miyagisan, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

“Mad” Henry of Fordwich

Henry of nearby Fordwich was suffering from what might have been a type of mental illness. His two caretakers drag Henry to St. Thomas’s tomb with his hands tied, prodding him with sticks as he rants and shouts. The monk Benedict recorded this incident and the scuffle that accompanied Henry’s arrival, with his cloak tousled in front of him, as depicted in the first roundel (at left in the photo). One caretaker’s cloak is caught on a candlestick, and the officiating monk is obviously worried as one hand steadies a lectern.

Henry of Fordwich, north ambulatory window, Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral. Photo: Anne-Marie Boucher, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

After spending the whole night at the Cathedral, Henry is calm and cured in the second scene, kneeling in appreciation with his cloak draped behind him. The group rejoices at his recovery, expressing amazement. As an offering of thanks, the rope that bound Henry and the beating sticks are left at the base of the tomb.

Henry of Fordwich, north ambulatory window (detail), Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral. Photo: Anne-Marie Boucher, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

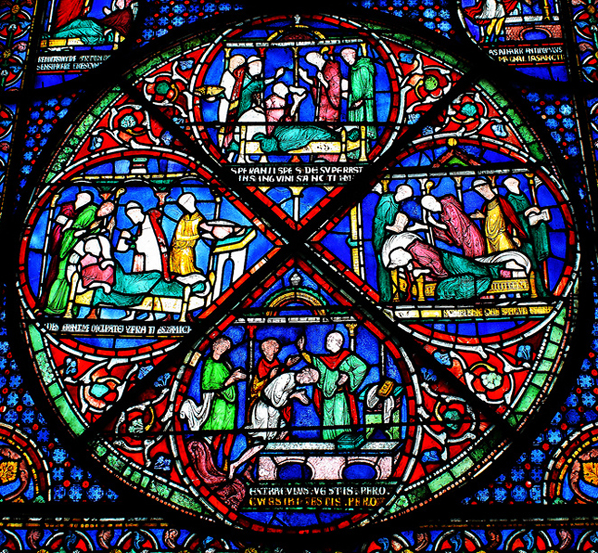

The Case of the Bleeding Monk

Benedict may have recorded this strange case of Hugh of Jervaulx who was a cellarer—a monk assigned the provisioning of a monastery. The first teardrop-shaped scene (at left in the photo) reveals a layman physician unsuccessfully tending to Hugh, who lies ill in bed as the Abbot of Jervaulx observes. As medieval visual culture expert M. A. Michael explains, “The ineffectiveness of surgeons and physicians is a theme in the miracles of St. Thomas.” Thus, the next scene (at top) portrays the Abbot stepping in to bless Hugh who drinks the holy water of St. Thomas.

Hugh of Jervaulx, north ambulatory window, Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral. Photo: Miyagisan, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In the third scene, blood pours from Hugh’s nose, rendered as a long red ribbon flowing to the floor, as he lay face down on his bed submitting to the “therapy.” At this point, one might wonder if the cure could be worse than the disease, but Hugh is nevertheless healed—another testament to the power of St. Thomas Becket.

Hugh of Jervaulx with nose bleed, north ambulatory window (detail), Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral. Photo: Miyagisan CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Miracles Past and Present

With such detail, these stories left me wondering, did these events actually occur? In our modern, more secular times, incredible tales might be explained by scientific or psychological intervention. Or would they? A recent survey from the Pew Forum on Religion found that some 80 percent of Americans—religious and non-religious, young and old—still believe in miracles in the 21st century. Regardless of whether the stories told to the Canterbury monks reflect fact or fiction, the Miracle Windows not only attest to the artistry and craftsmanship of the stained-glass masters of medieval times, they also speak to a continuing need to believe in healing, wonders, and divine intervention.

Discover more about Canterbury’s exquisite stained glass windows at the exhibition Canterbury and St. Albans: Treasures from Church and Cloister through February 2, 2014.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks