The Getty Research Portal is a free online search tool that aggregates records for digitized books and journals related to art history, which are contributed from libraries around the world, and makes them findable all in one place. Records in the Portal link to fully digitized and free-to-download publications useful for art historians, researchers, curators, students, and more.

To keep this project up and running takes an exceptional project manager. Her name is Anne Rana—call her Annie.

Annie’s role includes, among other things, identifying Getty Research Institute library books and journals for digitization, coordinating workflows and processes with numerous Getty staff and Internet Archive operators, and managing relationships with dozens of contributing partners.

Annie also works to secure new contributors from around the world and to expand the Portal’s audience. Recent partners have included art libraries and museums hailing from Brazil, Croatia, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the US.

Within the Getty, Annie works with the many catalogers, librarians, research assistants, imaging technicians, software engineers, and others who enable the digitization of the Getty Research Institute’s materials. Each year thousands of digitized books and journals from the collections are uploaded to the Internet Archive and made available through the Portal. In this post, you’ll meet several of the people who make this happen.

Origins of the Getty Research Portal

First, a word about the Portal itself. Spearheaded by Thomas Gaehtgens, now director emeritus of the Getty Research Institute, the Portal was conceived with the aim of unifying digitized versions of art historical materials dispersed among different websites, making them easier to find.

Intending to create a sustainable, collaborative, and international art bibliography for the digital age, the Portal was launched in 2012 with eight partner institutions and 20,000 volumes. While it began with a focus on assembling the literature of western art history (due to the nature of the digitized collections of its founding partners), the Portal has since expanded to pursue a wider view of the world’s art histories.

Annie Rana and Kathleen Salomon review upcoming milestones for the Getty Research Portal

Kathleen Salomon, chief librarian, associate director of the Research Institute, and the Portal’s founding manager, oversees the project in conjunction with Annie. The two meet frequently to discuss content and contributors, technological enhancements, and upcoming workshop and conference opportunities.

Step 1: Reviewing and selection

Serving also as the project’s content specialist, Annie works to identify and prioritize candidates for digitization from the Research Institute’s collection.

Books and journals related to art and art history are selected to be scanned for a variety of different reasons, such as:

- they are noted in an important art bibliography,

- they have not yet been digitized by another institution,

- they are part of a specific collection at the Research Institute, such as its emblem or festival rare book collections,

- their copy is unique in some fashion, such as possessing handwritten annotations in the margins, or

- a request was received for digitization from another institution as part of a coordinated digitization project.

In addition to targeting certain titles for priority digitization, the Research Institute is also systematically scanning most of its rare books shelf by shelf.

Library staff Erica Wofford at her desk, ready to start a day’s work.

Library staff such as Erica Wofford play a critical role in the digitization pipeline. She focuses on compiling lists of titles to be digitized—running a handy automated script through the library’s catalog to pull information from book records—and using the resulting spreadsheets to parse thousands of titles, checking to make sure that the volumes have not already been scanned, that they are in the public domain, and that they have been cataloged.

Erica then runs her findings by Annie, who gives the go-ahead for digitization. Once flagged, if a book has not yet been sufficiently cataloged, then cataloguing is its next stop—a critical activity in any library or archive.

Erica parses numerous lists of books as part of digitization assessment.

Step 2: Cataloging

Barbara LaMori organizing book titles to be cataloged.

If a book routed for digitization needs further cataloguing, Research Institute staff such as Barbara LaMori work to make sure the vital information is recorded, checking that catalog records meet RDA (Research Description and Access) standards and that records are properly stored within databases. If the metadata is not robust enough, Barbara and other Getty catalogers work to make it complete.

Barbara fills out fields such as title, author, publication date, and many others while cataloging,

including the unique aspects of a rare book.

Cataloged books to be sent to the scanners.’

Cataloger Susan Chow holds Chinese publications that are potential candidates for digitization.

The Research Institute is actively working to expand its holdings of books on Asian, Latin American, and African art. Catalogers such as Susan Chow, with expertise in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean, are vital in making sure that such titles advance to the digitization process. Susan has also helped to identify institutions in China and Japan, and reviewed their digitized holdings for potential Portal contribution.

Step 3: Pulling and prepping

The next step is checking on an approved book’s physical status. Erica and other library assistants collect books from cataloging or pull already-cataloged ones from the Research Institute’s open-stack shelves and vaults, performing a physical assessment to ensure that they meet criteria for scanning.

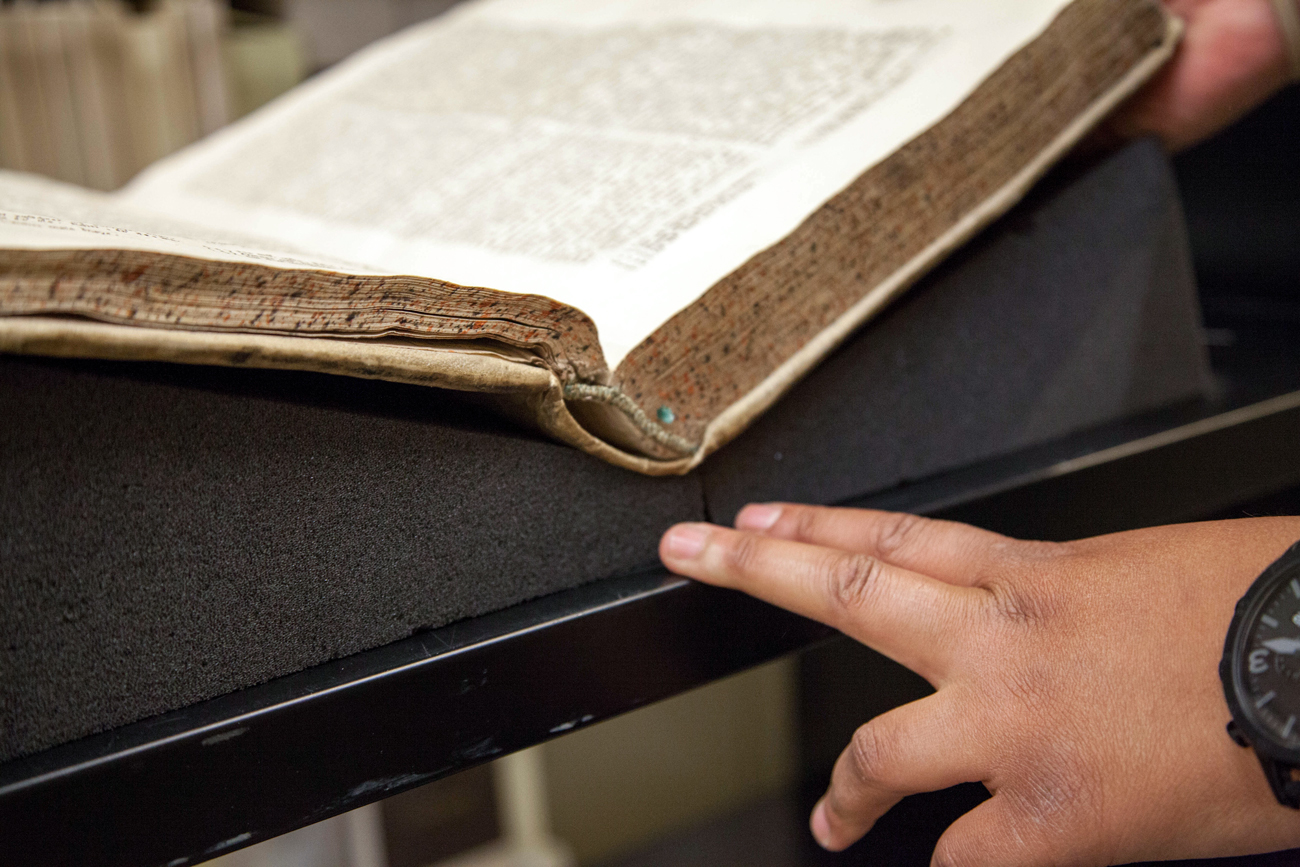

Erica places a book on special padding and checks for any loose pages as part of a physical assessment.

Erica checks on size, condition of the binding, loose pages, insect damage, and any other unique features that might make scanning difficult or result in physical damage to the book itself. She has the measurements of each of the Research Institute’s four scanning stations memorized and knows which machine can handle a particular book.

If a book requires special attention, it is routed to the complex book scanner, which is devoted to books that cannot be digitized by other scanning stations. And if the condition is particularly troublesome, a conservator must be brought on to assess the object.

Erica checks for any damage to the cover that would prevent this book from being safely scanned.

Double-checking the book’s binding to make sure it is stable for scanning.

The Getty has more books than the Research Institute’s space at the Getty Center can hold, so some of the collection is housed at a warehouse about 30 miles away, known as the Annex. Staff such as Veronica Nunez work in a role similar to Erica’s at the warehouse and meet with Annie regularly—going over lists, overcoming issues, and prepping books for scanning at the satellite location.

Annie and Veronica Nunez review lists of prioritized books for scanning that are housed at the Getty’s library annex.

Once this process is done, the book is sent to the appropriate scanner: like the Getty Center, the Annex also houses four digitization stations, including a complex book scanner devoted to texts that others are unable to digitize due to size or condition issues.

Stacks and stacks of books, as far as the eye can see.

Annie reviews oversize books at the Annex to determine whether they’re candidates for digitization.

This oversized book is in good shape for scanning.

Annie secures the book before putting it back on the shelf.

Digitization on Demand

Annie and Aimee Lind meet to discuss digitization-on-demand updates.

Aimee Lind, a reference librarian and the head of interlibrary loan, oversees an additional digitization process named Digitization on Demand. When researchers need a Getty book but can’t physically come to the Getty Center, physical materials can often be sent to them via interlibrary loan. But increasingly, the Getty also has the capability to create a digital surrogate of the book for research purposes if the title is out of copyright. If the materials requested by a researcher meet the criteria for the Portal, this quick-turnaround digitization process serves two purposes: it is sent to the inquiring researcher, and is made available on the Portal for others to access as well.

Aimee shows a handy form that researchers can use to request the digitization of materials.

Step 4: Scanning

Doug Marcchett, an Internet Archive scribe operator, demonstrates the process of scanning a book page by page.

Of course, the physical scanning of the books themselves is integral to the digitization process. Every page is meticulously scanned, either by Getty staff or by scribe operators working for the Internet Archive at both the Getty Center and at the Annex.

On the Internet Archive scribe, pages are pressed flat under glass before two overhead cameras shoot adjacent pages simultaneously.

An Internet Archive expert scanner places the book within a scribe and shoots the pages simultaneously using two cameras. These images can be seen on a monitor for a quality check. Then the page is turned and the process repeated.

Internet Archive ‘Republisher’ software helps make sure that books’ pages are lined up correctly and that no words or images are cut off.

A regular-sized, 300-page book generally takes about 20 to 40 minutes to scan, depending on condition and formatting. Checking and editing the photos for quality takes about 15 more minutes. After this, the record and scans are directly uploaded to the Internet Archive, where they can be found publicly by the end of the day.

The DT scanner, operated by Research Institute imaging technician Phil Warnecke, can handle larger books than the Internet Archive scribes are able to as long as the book is in good condition.

A row of periodicals ready to be scanned by an Internet Archive scribe at the Getty library Annex.

Internet Archive operator Edda Manriquez completes one of many books for the day.

Complex Scanning

At the Research Institute’s complex book workstation, Ava Porter handles a large and fragile volume, carefully turning page by page and shooting each with a single overhead camera.

So-called “complex books” require additional attention during scanning. Most complex books are simply oversized, but some are too small, have too-tight bindings or unique foldouts, or are especially fragile. Special handling, placement, lighting, weights, and patience are all involved in the imaging of these books, which is conducted by Ava Porter, the operator of the complex book scanner at the Research Institute.

Imaging technician James Gott prepares to capture a foldout on the Annex’s complex book workstation.

Step 5: Ingesting

Alyx Rossetti works on adding records for digitized texts onto the Portal.

Next comes access. No one would be able to find these digitized books in the Portal if it weren’t for software engineer Alyx Rossetti, who has worked on the project since 2013. She is in charge of adding records for newly digitized titles to the Portal.

Once Getty books are scanned, they are pushed onto the Internet Archive through the work of Lawrence Olliffe, an applications analyst at the Research Institute, who also oversees the subsequent processing that takes the metadata from those books in the library’s local catalog and adds the URLs that point to the Internet Archive record. At this point, Alyx normalizes the datasets and they are fed through a transformation code that enables their upload to the Portal. The transformation and portal code were all developed by Alyx and her information systems colleagues at the Research Institute.

Another part of Alyx’s role is to ingest records from the project’s contributing institutions, some of which have newly digitized material that she adds to the Portal on a quarterly basis. Additionally, Alyx and other members of the Portal technical team have developed a CSV file contribution option, as with the example above from the Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, that easily facilitates contributions from institutions that may not have standardized metadata. This enables more partners to join the project.

Connecting

Another part of the work of the Getty Research Portal is making sure that target users are aware of the project and can benefit from its resources. This happens throughout the year at conferences and workshops, led by Annie and members of the Portal team. Annie has presented at numerous conferences, such as the annual meeting of CAA (College Arts Association) and ARLIS (Art Libraries Society of North America), introducing the Portal to potential new users and contributing institutions.

An example tweet from @GettyHub’s #NewlyDigitized series.

Research assistant Toby Levers, meanwhile, helps spread awareness about particularly interesting materials added to the Portal under the #NewlyDigitized hashtag on Getty social media.

Toby also works with Research Institute curators to help identify newly acquired rare books and to make sure that their digitization is prioritized. Sometimes curators put together collections of titles on the Portal that complement exhibitions or can be shared as a resource with their scholarly peers.

A sample virtual collection on the Portal, which brings together alchemical titles compiled by David Brafman, associate curator of rare books and curator of the Research Institute exhibition The Art of Alchemy.

Future Plans

Portal.getty.edu homepage

Libraries, museums, and universities around the world have made digitization of their collections a priority and a key activity. Because of this, the Getty Research Portal continues to grow in records and contributors. As of July 2018, six years since the launch of the Portal, more than 140,000 digitized volumes have been made accessible there, from more than 30 international contributors—a number that grows regularly thanks to catalogers, librarians, scanners, software engineers, curators research assistants, archivists, and others.

Future plans for the Getty Research Portal include interface improvements to continually make browsing and filtering easier, eventual integration with data in the Getty Vocabularies and the Getty Provenance Index, and full-text searching. If you’re interested in using the Portal, please visit portal.getty.edu, and if you’re interested in becoming a Portal contributor, please contact Annie Rana.

Until next time!

The background research and photographs for this story took place over several months within the first half of 2018. While the portal process has remained the same, several of the people featured in this post have changed positions within the Getty. —Ed.

I enjoyed reading this article, especially as an introduction to the people and environment. It looks like a lovely place to work. I was particularly impressed by the speed with which your scribes are able to scan a book. Half an hour is so much faster than the (I think) 4 hours it took me to scan a 224 page book recently, and I’ll bet that your scans are far, far, far higher quality than what I was achieving!