Photograph of César Moro buried up to his head in sand, ca. 1935, unknown photographer. César Moro papers. The Getty Research Institute, 980029, box 1, folder 20

Peruvian poet César Moro has received relatively little notice in American scholarship. His poetry, artwork, and activities within and without the surrealist movement in Paris, Mexico City, and Lima remain little examined. But the Getty Research Institute exhibition Farewell to Surrealism: The Dyn Circle in Mexico, opening October 2, presents him as one of the key contributors to the art periodical Dyn as well as a central figure in the circulation of avant-garde ideas and aesthetics from the 1920s through the 1950s.

Profile of Head, ca. 1939, César Moro (Peruvian, 1903–1956). Emilio Adolfo Westphalen papers regarding surrealism in Latin America. The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.21, box 5, folder 3

Born Alfredo Quíspez Asín in Lima, Peru, he changed his name to César Moro at the age of 20 after a character by author Ramón Gómez de la Serna. Having studied French in Lima, Moro left for Paris in 1925 to pursue dance and art, but art and poetry became his main interests, and he exhibited in collective shows in Brussels in 1926 and in Paris in 1927. He entered into the exchange of ideas and art with the likes of André Breton, Paul Éluard, Benjamin Péret, and, outside the surrealist group, Henri and Simone Jannot.

The versatile poet quickly adopted French as his second writing language and was the only Latin American poet to contribute to André Breton’s surrealist journals of the 1920s and ’30s. Despite his relocation to Paris, Moro continued to publish in Latin America, including in the Peruvian periodical Amauta no. 14 (April 1928), which printed “Oráculo” (“Oracle”), “Infancia” (“Childhood”), and “Following you around.”

In Paris, Moro was active in political protests through his involvement in the writing of the 1933 anti-war manifesto “La mobilisation contre la guerre n’est pas la paix” (“Mobilization against the War is Not Peace”). He added a note condemning Peruvian dictator Sánchez Cerro’s bloody suppression of an uprising by sailors against poor nutrition and cruel discipline. After his return to Lima in 1934, Moro continued to write against those in power. The police of dictator Óscar Benavides entered Moro’s home and confiscated copies of his clandestine pamphlet CADRE (Comité de Apoyo a la Repúbica Española [Support Committee of the Spanish Republic]), which supported the Spanish Republic. Finally, in 1938, he was forced to flee Peru as a result of police harassment.

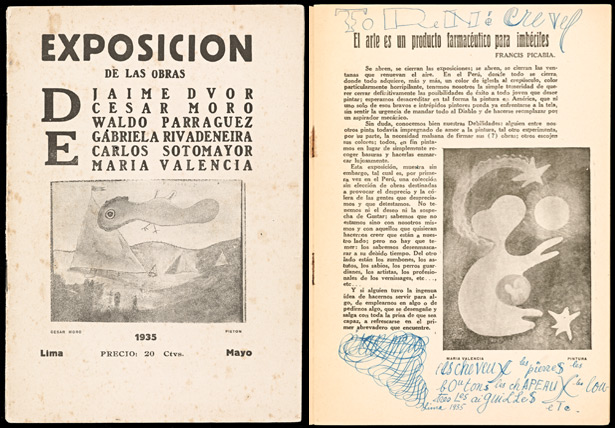

Moro went to Mexico City, which was proving to be a haven for immigrants fleeing from a variety of political or artistic tensions. There he befriended progressive artists such as Wolfgang Paalen, Alice Rahon, Eva Sulzer, Xavier Villaurrutia, Remedios Varo, Gordon Onslow Ford, and Leonora Carrington. In turn, Moro introduced Breton to the Mexican modernist group Los Contemporaneos (The Contemporaries). Mexico City’s nexus of avant-garde thinkers and artists resulted in the 1940 Exposición internacional del surrealismo (International Exposition of Surrealism) at the Galería de Art Mexicano, organized by Wolfgang Paalen and Moro with Breton’s guiding hand from New York. Previously Moro had staged at least two other surrealist exhibitions—the earliest in Lima in 1935 with Chilean artists María Valencia, Jaime Dvor, Waldo Paaraguez, Gabriela Rivandeneira, and Carlos Sotomayor.

Cover of Exposición de Las Obras de César Moro, Jaime Dvor, Waldo Parraguez, Gabriela Rivadeneira, Carlos Sotomayor, María Valencia (left) and introduction to catalogue by César Moro (right), Lima, 1935. César Moro papers. The Getty Research Institute, 980029, box 2, folder 1

In Mexico City, Moro became closely associated with Paalen and the journal Dyn. The journal offered Moro the opportunity to publish his French-language poetry, but also allowed him the space to expand on the ideas he had explored with his collaborator Emilio Westphalen in the only issue of a previous journal, El uso de la palabra (The Power of Words), in which he explored indigenous culture as subject matter.

Moro was prolific in Mexico: in addition to Dyn, he published frequently in the periodicals El Hijo Prodigo (The Prodigal Son) and Letras de México (Letters from Mexico). As a result of his connections with Paalen, Moro also had two publications of his poetry, Le chateau de grisou (Firedamp Castle) and Lettre d’amour (Love Letter), and numerous translations of his surrealist and avant-garde texts circulated.

Title page of Lettre d’Amour by César Moro with frontispiece by Alice Paalen (Rahon). Mexico City: Ediciones Dyn, 1944. The Getty Research Institute, 980029.3, Box 1, Folder 9

Moro, who was gay, led a self-described “vida escandalosa” (“scandalous life”) quietly and privately. Many fellow surrealists were unaware of Moro’s homosexuality, which he embraced for the first time in Mexico. His love poetry written in Paris is tortured, but his poetry written in Mexico City for La tortuga ecuestre (The Equestrian Turtle) is openly homoerotic. His new, passionate language can be attributed to his relationship with army lieutenant Antonio A. A. In fact, Moro wrote a series of letters and poems throughout 1939 that express the cruelty of his love for Antonio, the totality of his feelings that leave nothing in his life beyond Antonio. The strength of Moro’s feelings for him lasted the duration of his residency in Mexico, even after Antonio married and became a father. Moro appears to have played an almost godfather-like role in the life of Antonio’s son.

The intensity of Moro’s relationship with Antonio coincided with his rift with Breton and surrealism after the publication of Breton’s Arcane 17, which Moro challenged in a review in El Hijo Prodigo (The Prodigal Son). From then on Breton, who could not accept love between members of the same sex, would no longer have as great an impact on Moro’s aesthetic development. Moro turned to figures such as Paalen for artistic and theoretical direction.

In 1948 Moro returned to Lima, where he wrote poetry for La Revista de Guatemala (The Magazine of Guatemala) and Las Moradas (Dwellings) and taught French at the military college Leoncio Prado. He made his last public appearance in 1954 at a conference on Marcel Proust (who had an immense impact on him), delivering a paper entitled “Amado y admirando apasionadamente” (“Passionately loved and admired”). Moro’s scandalous life ended on January 15, 1956. Much of his poetry and prose was collected and published posthumously by his lover and literary executor André Coyné.

At the Getty Research Institute we are fortunate to have César Moro’s papers, which include his letters, drafts of poems, diaries, and photographs. These provide a treasure trove of scholarly material, which we have drawn on for the exhibition Farewell to Surrealism. The exhibition presents several photographs of Moro, selected writings contributed to Dyn, along with the publications Château de grisou and Lettre d’Amour.

Regarding this essay above:

“From then on Breton, who could not accept love between members of the opposite sex, would no longer have as great an impact on Moro’s aesthetic development.”

Don’t you mean to say “members of the same sex” ? The information you are sharing is that Breton had a problem with homosexuality, isn’t it? Moro ceased to be influenced by Breton because of Breton’s attitude toward Moro’s homosexuality. Or am I misunderstanding something here?

Sheri, you are absolutely right. This was an editing error, and we’ve now fixed it. Much appreciated! —Annelisa/Iris editor

Please , what is ,, absolutely right ,, / Breton have been , yes or not , gay ? On the other hand , what reg. the avanguarde group , Tristan Tzara , Victor Brauner and all around Breton ?

Thank you , L

Thank you for sharing this. I am the great-grand-niece of Cesar Moro and I am so happy to have found this article!

Thanks for this article, very interesting, I’m the grand-nice of Cesar Moro .

After a first look in the “César Moro Papers” notice, I just want to point out a mistake concerning the document in Box 8 with this title: “César Moro : retrospectiva de la obra plástica”. This publication was done in Lima (Peru), not in Arequipa as mnetioned in the notice (Arequipa is the name of an avenue, and Miraflores, in the catalogue, is the name of a district in Lima).

I make this remark as the coordinator of this ctalogue in 1990 and a reseacher on Moro.

Congratulations for your good work!

Daniel Lefort