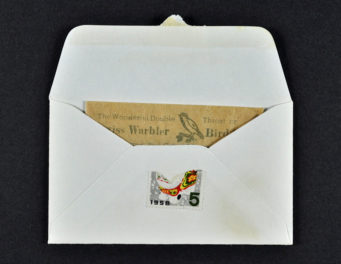

Envelope containing a letter from Lawrence Alloway to Sylvia Sleigh, February 2, 1948. Alloway addressed mail to Sleigh under her married name, Greenwood. The Getty Research Institute, 2003.M.46

“I love you, madly, intellectually, impulsively, constantly.” So writes Lawrence Alloway to Sylvia Sleigh in a letter from 1949. Two troves of letters between the art-world couple are part of the Getty Research Institute’s collection, and 1,000 items from the correspondence records of both Sleigh and Alloway have recently been digitized and made viewable online in order to facilitate scholarship on these important figures.

The letters are primarily from the midcentury—from the 1940s to 1970s—with some materials dating to the 1980s and 1990s. The letters also trace the evolution of the pair’s intellectual and romantic lives over several decades, with plenty of poems and drawings sprinkled throughout.

Poems sent by Alloway to Sleigh (“my lady Sylvia”) in a letter dated July 1948. The Getty Research Institute, 2003.M.46

A Painter and A Critic

Sleigh was a realist painter and feminist art activist from Wales. Alloway was a British-born art critic and curator. The two met at an evening art history class at the University of London in 1943. Sleigh, who was ten years older than Alloway, was already married. She divorced her husband in 1954 and wed Alloway shortly thereafter.

In 1961 the couple moved to New York, where Alloway was hired as the senior curator at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Over the course of the decade, he championed abstract expressionism, geometric abstraction, and pop art. Sleigh, who is best known for her paintings of male nudes, became one of the founders of SOHO 20 Gallery, an all-women artist-run space, and joined A.I.R. Gallery, a female cooperative.

Letter from Alloway to Sleigh sent in November 1949 enclosing a catalogue and card for an art exhibition including Sleigh’s work. The Getty Research Institute, 2004.M.4

Card for a London art exhibition including Sleigh’s work, sent by Alloway in November 1949. The Getty Research Institute, 2004.M.4

Long-Distance Love

Alloway and Sleigh spent extensive time apart in the early stages of their relationship, so they relied on the postal service to remain connected. They exchanged letters frequently, discussing all matters of daily life, their professional work, and, most thoroughly, their love for one another.

The collections include handwritten and typed letters, telegrams, postcards, and news clippings. Alloway often added poems and drawings to his letters, particularly sketches of his alter ego Dandylion—a human lion—engaged in all sorts of quotidian activities, from reading and sleeping to sunbathing and paying a library fine. He occasionally refers to Dandylion in his writings; in a letter from 1950, Alloway notes how Dandylion’s “tail curled up with pleasure” while reading Sleigh’s latest missive.

Because they document the details of Alloway’s travels, contacts, writing projects, and thoughts about the art world, the letters are a rich trove of information for scholars about his intellectual circle, as well as broader trends in art history. For example, the letters were important sources consulted by authors for the Getty Research Institute’s recently published book on Alloway.

Letter from Alloway to Sleigh, February 2, 1948. “I feel very lonely in your absence,” he writes. The Getty Research Institute, 2003.M.46

Telegram from Sleigh to Alloway, January 1952. “All is well. Please phone tonight.” The Getty Research Institute, 2003.M.46

Mutual Muses

Despite the geographic distance between them, Alloway and Sleigh remained supportive of each other’s work. In a letter dated December 22, 1948, Alloway wrote, “I adore your painting. The synthesis of the different rhythms of growth is wonderful. The summer-snow of the blossom, the exquisite tone of the upper trunks on the blue sky, is so delicate and yet impetuous too.” A few days later, he offered further praise: “Your feeling for nature charms me so much: this painting is like a rose bush responding to the music of Orpheus, you have caught its life and desire.”

In the early 1950s, Alloway was part of the Independent Group at the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, and lectured at the National Gallery and Tate Gallery. Sleigh often inquired about his lectures and writings. “I’m so glad that your lecture on Claude went well—a delightful subject,” she wrote on December 4, 1952, adding, “I hope that your Banstead lecture was successful too—I should like to hear a lecture on Bellini—I feel I have forgotten all I know about the Venetians.” In an earlier letter, Sleigh brought up a writing project: “I’m glad you are working on your film book again. The film ‘Talk about a Stranger’ sounds very interesting. I should love to see it with you.”

The effusive language and repeated terms of endearment—“my lion,” “my muse,” “my ravishing Minerva,” to name just a few—in Sleigh and Alloway’s letters illuminate their relationship as not only one of mutual love, but also admiration and inspiration.

The digitized letters are freely available online; find them here.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.