Curator John Tain assists with unpacking materials from the Shunk-Kender archive at the Getty Research Institute. Photo: Marcia Reed

Harry Shunk and János Kender are the eyes through which we look back on the groundbreaking art of the last century. Photographing the avant-garde artists, landmark exhibitions, and radical events of the 1950s through 1980s—first as a collaborative duo and then as independent photographers—the two men shaped our impressions of what now constitutes the history of postwar art.

The Shunk-Kender archive, containing nearly 200,000 prints, negatives, contact sheets, slides, and transparencies, was generously donated by the Roy Lichteinstein Foundation to a five-institution consortium: the Getty Research Institute, Museum of Modern Art, National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., Centre Pompidou, and Tate. The Getty now holds the only almost-complete sets of master prints, numbering about 19,000, as well as all the negatives and contact sheets.

Covering the work of more than 400 artists, the pair extensively photographed visionaries such as Lucio Fontana, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Merce Cunningham, E.A.T., Yayoi Kusama, Robert Rauschenberg, Dennis Oppenheim, and Vito Acconci, among many others. Shunk and Kender were Roy Lichtenstein’s favorite photographers; this insider access was critical to their success.

Harry Shunk (left) and János Kender in 1961 at a dinner for artist Lucio Fontana at La Coupole in Montparnasse, Paris. Photo: Shunk-Kender. The Getty Research Institute, 2014.R.20

A History-Making Partnership

Harry Shunk was born in Germany and moved to Paris as a teenager, working as an assistant in a photography studio. János Kender fled to France from his native Hungary in 1956 to escape the Hungarian Revolution. The two joined forces in 1958, forming a professional and romantic relationship and building their careers and reputations around photographing the most significant artists of the era.

In Paris they were part of a close-knit circle of artists through their association with Galerie Iris Clert and Galerie J, following artists such as Niki de Saint Phalle, Jean Tinguely, and Jean Fautrier. They developed a strong rapport with Ileana Sonnabend, who popularized American art in Europe, and the duo documented nearly all of her gallery’s exhibitions. In 1967 Shunk and Kender moved to New York City and began to engage with postminimalist, conceptual, and performance-based work. They photographed exhibitions at the Leo Castelli gallery, and became involved with artists such as Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, Lee Bontecou, and Richard Serra.

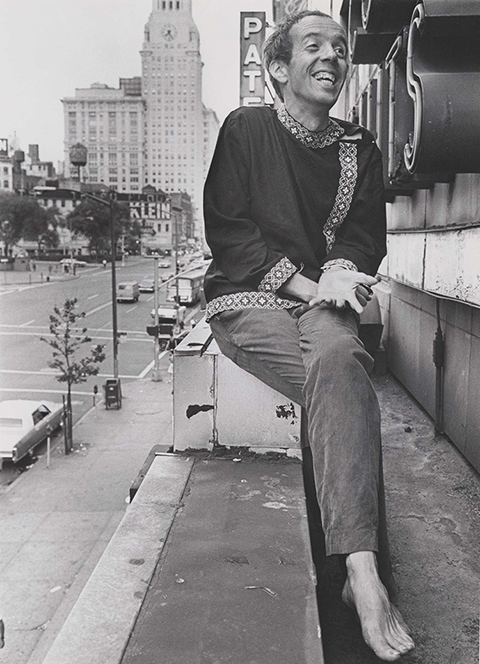

Taylor Mead in New York City, 1966, Shunk-Kender. The Getty Research Institute, 2014.R.20

Their partnership ended in 1973. Shunk accepted the rights to their work from Kender and continued to work independently. In spite of their importance to the history of postwar art, both photographers died in obscurity in the early 2000s. Shunk’s archive was found in precarious but well-preserved condition within his cluttered, hoarder-style apartment. It was purchased by the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation and later disseminated among five art institutions.

Documentary Photographers or Artist-Collaborators?

While the breadth of the archive is staggering, the depth is equally impressive. Shunk and Kender developed close relationships with many of the artists they photographed. Rather than pure documentation, their photographs fall closer into the realm of artist-photographer collaboration. They had a particularly robust alliance with Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Following the artists’ fabric wrapping of the Trocadéro in Paris in 1964, Shunk and Kender became Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s de facto photographers and continued to record all their ephemeral, site-specific projects throughout the 1960s and 70s.

Shunk and Kender were also involved in creating some of the most iconic images of the last century, including Yves Klein’s photograph Le Saut dans le vide (Leap into the Void) from 1960. They used an inventive montage technique to create the appearance of Klein launching himself from a rooftop with nothing below to break his fall. The photographers later documented Klein’s infamous Anthropométries events in the early 1960s, in which naked female models covered in the artist’s signature blue color became “living paintbrushes.”

A hint of the riches in the archive: a set of photographs of artist Joseph Beuys. Photo: Marcia Reed

Capturing Groundbreaking Moments

Though based in New York, Shunk and Kender travelled extensively, documenting events such as the Venice Biennale, the Bienniale of Paris, and World Expos in Montreal and Osaka. They also covered many key exhibitions of the era, including Harald Szeemann’s When Attitudes Become Form (1969), the show that fittingly inaugurated a new era of curator as artist collaborator, and The Bachelor Machines (1975).

The archive also includes extensive material on Willoughby Sharp’s innovative project, Pier 18. In 1971, 27 artists devised and carried out performances along an abandoned pier on the Hudson River. Shunk and Kender worked with the artists to capture their events; the resulting images were not strictly documentation but rather part of the artistic output of the project itself. As such, the photographs were later exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

A Rich Legacy

Shunk and Kender not only captured the artists, artworks, installation shots, exhibitions, events, and candid moments of the postwar years, they captured the changing zeitgeist of the era. Because they were equally adept at shooting people and objects, static spaces and movement, their photographs also manage to also evoke more intangible elements: the mood, energy, and essence of particular moments in history.

Their prolonged engagement with artists over decades resulted in a rich trove of photographs tracing the evolution of art over time. Shunk and Kender crossed the divide between documentary photographers and artists in their own right, making significant contributions to the stories of avant-garde art.

Stories soon to be uncovered: a portion of the Shunk-Kender material, newly arrived in the Getty Research Institute vaults

The Shunk-Kender archive will be made available to researchers once it has been catalogued.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.