Props used in the Guerrilla Girls’ actions: plastic gun, bananas, and gorilla fingers with nail polish. The Getty Research Institute, 2008.M.14. Copyright © Guerrilla Girls, courtesy guerrillagirls.com

In 1994 curator Marcia Tucker, whose papers are now held at the Getty Research Institute, organized an exhibition at the New Museum in New York entitled Bad Girls. The show analyzed a wave of art from the 1980s and early ‘90s dealing with feminist issues, presenting practices substantially different from those of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, the epoch commonly defined as l’âge d’or of feminist art. These bad girls, who were actually also boys, were working on the same old issues of sex, gender representation, and the condition of women in society, but with a new twist: they did not fear to go “too far,” to be irreverent, unladylike, sometimes even vulgar. The bad girls were fun, were saying it all, and were saying it right in your face.

The show featured an anonymous group of artists called the Guerrilla Girls, the “conscience of the art world” as they proudly called themselves. The group was formed in 1985 by art professionals wearing gorilla masks—what is more unladylike than a gorilla mask?—and calling themselves by the names of dead and largely underrated female artists from all epochs: Rosalba Carriera, Käthe Kollwitz, Artemisia Gentileschi, and others. They used gorilla masks to help maintain focus on the issues they were presenting, rather than on their individual personalities and practices. Furthermore, the masks were a necessity, as they couldn’t afford to lose their day jobs.

Mask used by the Guerrilla Girls in their actions. The Getty Research Institute, 2008.M.14. Copyright © Guerrilla Girls, courtesy guerrillagirls.com

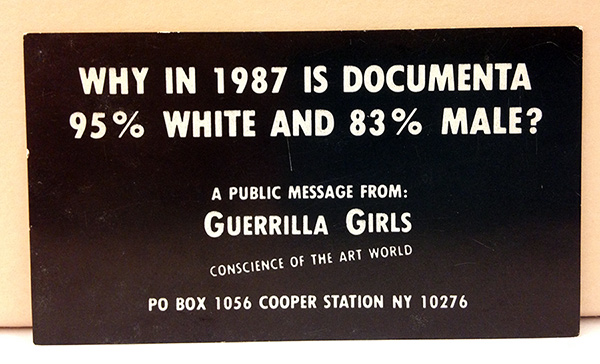

The Guerrilla Girls had good reason to fear for their jobs: the group began by covering Lower Manhattan walls with posters full of statistics about discrimination against women artists and artists of color, listing people’s names and unquestionable, shameful facts. For example, the poster below listed the galleries in New York City devoting 10 percent (or even less) of their shows to women artists, while the calling card they distributed at documenta 8 in 1987 exposed the fact that white and male artists dominated the pool of artists in the exhibition.

“These Galleries Show No More Than 10% Women Artists Or None At All,” one of the very first posters plastered at night by the Guerrilla Girls in SoHo in 1985. The Getty Research Institute, 2008.M.14. Copyright © Guerrilla Girls, courtesy guerrillagirls.com

Guerrilla Girls’ calling card passed out at the opening of documenta 8, Kassel, 1987. The card was kept by curator Harald Szeemann in his Artist files. The Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30. Copyright © Guerrilla Girls, courtesy guerrillagirls.com

They then broadened their targets to include social and political issues such as abortion, gay and lesbian rights, the politics of the Bush era, and violence against women. The severe look of the posters, for the most part in black and white with no images, was at odds with what is traditionally labeled as “feminine,” reproducing instead the cold aesthetics of (mostly male) conceptual art.

Compared with the works of other artists active in the domain of institutional critique, the Guerrilla Girls’ art reached a new level of aggressiveness in order to confront the cultural politics of art institutions in the ‘80s, which were far more conservative than those of the previous decade. In addition to reaching their public by wild posting and mass mailing, the group started suggesting guerrilla actions in museums, such as using restrooms as exhibition spaces or correcting interpretive labels for paintings.

“You’re Only Seeing Half the Picture” poster project, 1989, Guerrilla Girls. The Getty Research Institute, 2008.M.14. Copyright © Guerrilla Girls, courtesy guerrillagirls.com

The Girls decided to go all the way, and have continued to do so ever since: in their posters as well as in their performances, lectures, interviews, exhibitions, and publications, they have named names, showed numbers, quoted sources, and presented bare facts that the public is invited to elaborate. In The Guerrilla Girls Review the Whitney, a 1987 exhibition at Clocktower in New York, the group analyzed and exposed the politics behind the Whitney Museum, scrutinizing the choice of artists for the Biennale through the decades, the acquisition policy and the often not-so-transparent network of relationships (and money, lots of money!) among curators, sponsors, trustees, and politicians.

“Well Hung at the Whitney – Biennial Gender Census 1973-87”, draft for a poster featured in the exhibition The Guerrilla Girls Review the Whitney at the Clocktower, New York, 1987. The Getty Research Institute, 2008.M.14. Copyright © Guerrilla Girls, courtesy guerrillagirls.com

The Guerrilla Girls records at the Getty Research Institute, acquired in 2008, include in almost 100 boxes all the documents on the group’s activities from 1985 to about 2003: the complete series of poster projects, research and administrative material on publications, exhibitions, lectures, and performances, and even gorilla masks, wigs, and bananas. The records represent an invaluable source for the study of the evolution of feminist art and the awareness of women artists at large, and complement an already large trove of archives at the Research Institute, such as the papers of Eleanor Antin, Yvonne Rainer, Carolee Schneemann, Sylvia Sleigh, and the newly acquired Barbara T. Smith archive.

We are still far from an equal society, and not only in the art world. That’s why the “bad girls” are still out there, fighting for the time when their work will no longer be needed.

The Guerrilla Girls archive is available for study by qualified researchers.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.