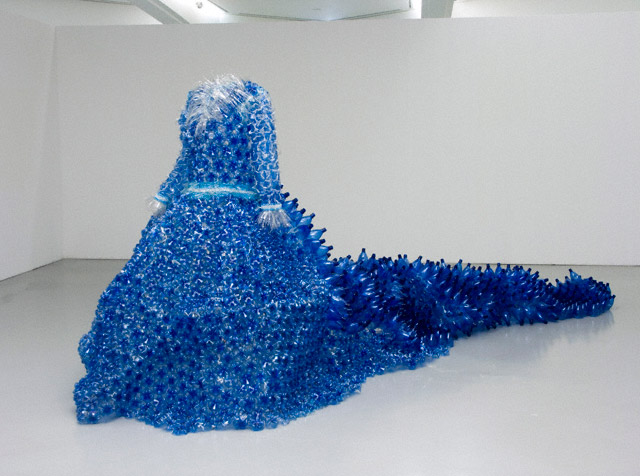

Vestito Blu, Enrica Borghi, 2005. Mineral water bottles, plastic bags, and plexiglas, 85.8 x 85.8 x 263.3 in. (220 x 220 x 675 cm). Collection Mamac, Nice. Photo: Muriel Anssens. © Enrica Borghi

Plastics have influenced every facet of modern life—from Ziploc baggies and dishes to car parts, essential hospital equipment, and the ubiquitous water bottle. The extraordinary versatility of the material also has made it a very attractive material for designers, architects, and artists.

But unlike with, say, oil paints, curators and conservators have very little knowledge about the composition and aging of synthetic polymers. This makes their care and conservation difficult, to say the least.

Take, for example, Enrica Borghi’s impressive 2005 work Vestito Blu, made principally from mineral water bottles and plastics bags. It’s not known how the various plastics will alter with time, or which display or storage conditions might be the most effective in slowing any potential deterioration.

Plastics were first introduced at the end of the 19th century, and came into widespread use in the 1950s—sixty years ago. Time enough for them to begin to need treatment. Many types of plastic are already exhibiting serious signs of deterioration that often appear with little or no warning—discoloration, crazing and cracking, warping, becoming sticky, and in extreme cases, turning completely to powder. The potential for catastrophic changes in certain classes of plastic, along with the sheer number of plastics available, constitutes a huge challenge for the conservation profession. There is an urgent need for information on the composition, physical and chemical properties, and aging behavior of a range of plastics if they are to be treated and preserved for the future.

Thankfully, a large consortium of research laboratories from France, the Netherlands, Denmark, Italy, Slovakia, Slovenia, and the United Kingdom recently received funding from the European Commission to initiate a three-and-a-half year project on the study of plastics.

The project, in which the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) is a full partner, is called POPART, or the Preservation of Plastic ARTefacts in museum collections. Together, the group aims to develop strategies to improve the preservation and maintenance of plastics objects in museum collections. By coordinating scientific studies and gathering experiences from all partners, the group hopes to establish recommend practices and identify the risks associated with exhibiting, cleaning, protecting, and storing these objects.

The GCI’s portion of this project is part of its larger Modern and Contemporary Art Research initiative, which takes a broad approach to the needs of this area of conservation, including a range of scientific research projects and collaborations.

The hope is that the GCI will be able to add to the body of knowledge on plastics conservation so that pieces like Vestito Blu can be preserved for future generations of museumgoers.

Comments on this post are now closed.