A set of mysterious marks by Degas sparks a quest through the pages of his personal sketchbook

The mysterious drawing in question. Abstract Lines, about 1877, Edgar Degas. J. Paul Getty Museum.

This humble drawing is by Edgar Degas.

Degas? When we posted this drawing on the Getty Tumblr, a few were quick to say that “this isn’t art” and wonder why it would belong in a museum collection. I can see why. When such a simple drawing, with such a blockbuster name attached to it, is taken out of context in a digital space, it can be pretty confusing.

But what is represented on this page? Was Degas sipping a little too hard on the absinthe? Was he testing a new set of chalks? Was he drawing from memory?

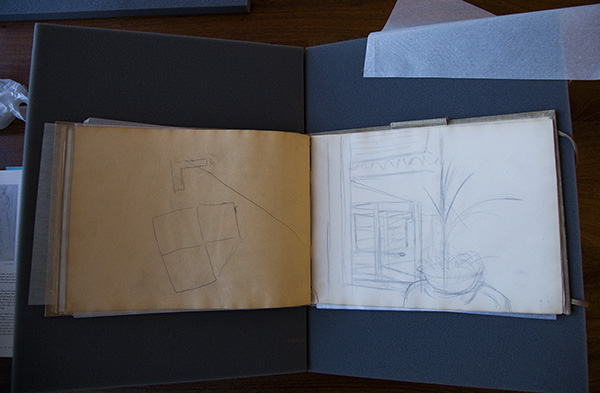

A seemingly simple book is actually a treasure trove of original sketches. An Album of Pencil Sketches, about 1877, Edgar Degas. J. Paul Getty Museum.

In fact, this drawing is just one page in a sketchbook by Degas that contains studies for his work. The answers to my mystery, I thought, might be inside. So I took my questions to Edouard Kopp, a curator in the Museum’s Department of Drawings. He brought out the real sketchbook from the vault so we could examine Degas’s work in the flesh.

Detail of cafe singers from page 11 of the sketchbook

Though it comes in a lovely red box, the sketchbook itself is quite worn. It’s full of unfinished drawings, hastily sketched scenes, quickly rendered (and re-rendered) characters, and blank pages, too. Smudges, handwritten notes, and even fingerprints greet you as you page through the book.

Detail of page 35 of the sketchbook

Among Degas and his friends, Edouard said, sketching was seen as a form of social jousting. Contrary to the idea of an artist studiously scribbling away in solitary, Degas in the 1870s was very cantankerous and—worse—was rubbing shoulders with a very controversial group of painters: the Impressionists. This particular sketchbook carries with it the acknowledgement that it “had been executed at [his friend Ludovic Halevy’s] in the course of intimate evenings, as an accompaniment to conversation.”

Page 21 of the sketchbook

As Paris developed into a city of movement and spectacle in the 1870s and ’80s, the café-concert became a venue for opulent displays of what had previously been street entertainment. Café singers, which appear on the sketchbook’s pages, were often associated with prostitutes in the minds of the upper classes. The café-concert was an object of simultaneous fascination and disgust to writers and artists such as Degas.

Detail of page 37 of the sketchbook

Degas’s depictions of singers verge on caricature. They reveal not only sumptuously shaped costumes, but exaggerated facial features and sometimes-unflattering takes on human physiognomy. You can almost hear bawdy tunes escape from the scribbled mouths.

The sketchbook shows evidence of Degas’s growing artistic interest in Parisian cafés, singers and dancers, and other denizens of Paris’s nightlife deemed “lowlife.” As Degas departed from his rigorous academic training to depict unconventional subjects in his paintings, his sketchbook more freely recorded this trajectory.

The mysterious drawing and the page opposite. Are they related? Pages 54 and 55 of the sketchbook

And as for the seemingly abstract, hermetic lines in the drawing that first sparked my quest? They may have served as a basis for the more elaborate sketch on the opposite page, which may be complex geometrical forms for a rendering of a potted plant on a table in front of a mirror. The “right” answer may only be in the mind and hand of Degas.

The sketch puts me in mind of Christopher Lloyd’s words in the introduction to his new book, Edgar Degas: Drawings and Pastels. Degas, he says, “falls into that rare category of artists—Leonardo da Vinci, Dürer, Raphael, Michelangelo, Rubens, Rembrandt, Watteau—of whom it can be said that every mark they make on paper is worthy of consideration.”

Why the sketchbook is in a museum is clear. It offers a window into the eye and mind of one of the greatest and most original draftsmen of the 19th century. A book in which direct experiences were hastily drawn, famous influential artworks were copied, and copious studies for finished paintings were kept is like a treasure chest. Flipping through the book is like hopping into a time machine back to the 1870s and sitting with Degas at a Parisian café, ready to enjoy the show.

L: The Convalescent, about 1872 – January 1887, Edgar Degas. J. Paul Getty Museum. R: Detail of page 4 of the sketchbook

Comments on this post are now closed.