The Getty’s collections offer a glimpse of the central role that China’s exports played in shaping the premodern European imagination of the “East,” as well as the many ways in which China served as a model of power and belief. These themes are the focus of a gallery course on June 4 from 2:00 to 5:00 p.m., which the three of us will be teaching, and which we’ve adapted here for The Iris.

Chinese art is in focus at the Getty this spring and summer with the exhibition Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road (through September 4), which explores one of the greatest repositories of medieval Buddhist art in the world. Combining gallery visits and group discussion, our course explores the many ways Asian art and ideas influenced Europe in the medieval and Renaissance worlds.

Manuscripts and Cross-Cultural Exchange

In the manuscripts gallery is a related exhibition, Traversing the Globe through Illuminated Manuscripts (through June 26), which transports the visitor to the premodern world, a time in which peoples, ideas, and objects (specifically book arts) traveled across Europe, Africa, and Asia with great frequency.

A Christianized Buddha

The story of the Buddha, for example, reached European audiences by way of the tale of Saints Barlaam and Josaphat, a Christianized version of the Buddha story. (The name of the protagonist, Josaphat, is a Latin version derived from the Sanskrit word bodhisattva, or one who leads others to enlightenment.) In the exhibition, visitors can explore this medieval game of telephone through book arts from India and Timurid Persia.

Josaphat Meeting a Blind Man and a Beggar from Barlaam and Josaphat, 1469, follower of Hans Schilling from the Workshop of Diebold Lauber. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 9, fol. 31v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Mapping the Known World

For many people in premodern Europe, the easternmost point geographically—on maps and in the mind’s imagination—was the biblical Garden of Eden. This idyllic, enclosed, and guarded terrestrial paradise was thought to be located east of India, which generally meant the easternmost inhabitable place on the globe. This meant that Eden was virtually inaccessible, beyond the wall of fire that guards it, of course.

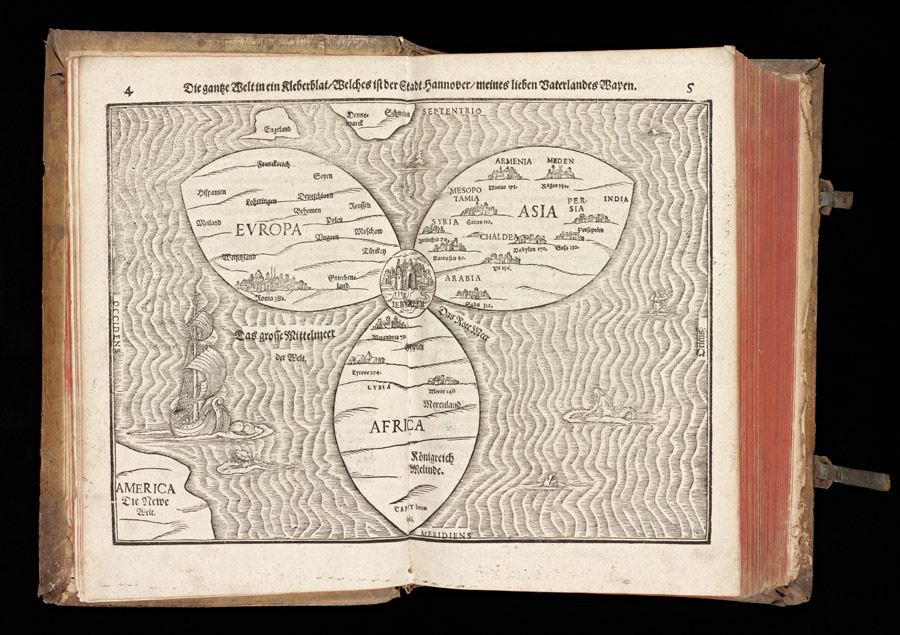

The German theologian-cartographer Henrich Bünting designed a map of the world in the shape of a clover, with Jerusalem as its center (a core concept for medieval Christians) and with Europe, Africa, and Asia connected as equal-sized petals. Elsewhere in the book, Europe is anthropomorphized into a queen and Asia is envisioned as the winged horse Pegasus, whose tail is Quinsay (China).

The World as a Clover Leaf with Jerusalem at the Center in Heinrich Bünting, Travel through Holy Scripture (Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae, Magdeburg, 1597). The Getty Research Institute, 44-2. All rights reserved

Stories of Silk

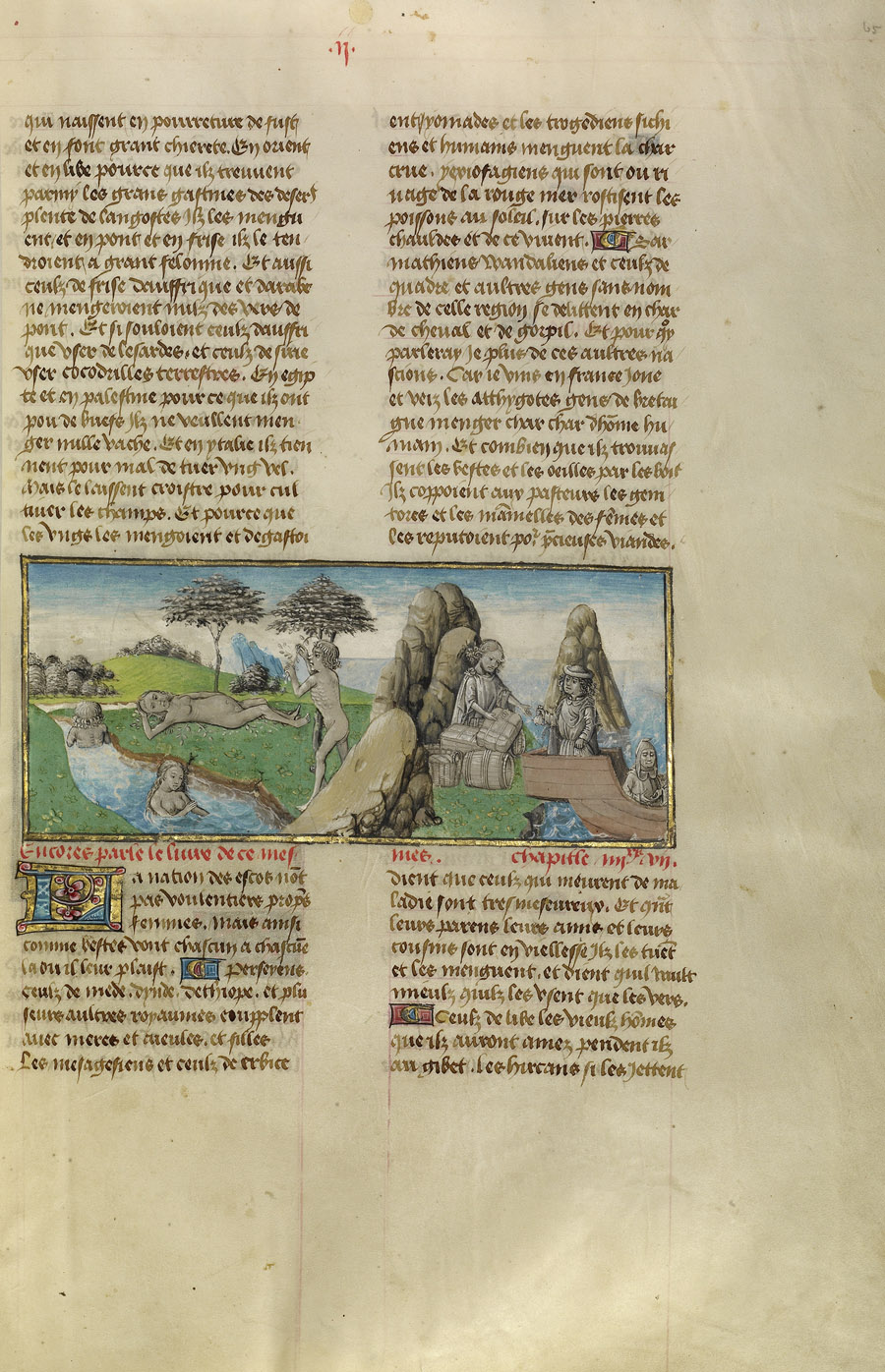

Europeans knew about China, or at least the far East, via the silk trade that took place across many Silk Road land passages and waterways connecting the Pacific to the Atlantic across Afro-Eurasia. The third-century Roman author Solonius described the so-called “Seres” people as the inventors of silk in the distant East, past Persia and India and beyond the realms of the Hindu ascetics. The Seres were believed to go about naked, gathering silk from trees and washing the raw materials in streams in a land hidden beyond a range of mountains, thereby keeping their production methods secret.

In the thirteenth century, the Dominican writer Vincent of Beauvais compiled a world history beginning with creation in Eden and ending in 1254; his sources for the East came from a range of authors, including the Franciscan missionary John of Plano Carpini and numerous ancient geographers, including Strabo and Ptolemy. The common thread in these accounts: stories of silk.

Bankers and Silk Merchants, about 1475, unknown illuminator, made in Ghent. From Vincent of Beauvais and Jean de Vignay, Mirror of History. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and gold paint on parchment, 17 1/4 × 12 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIII 5, vol. 1, fol. 65. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Byzantine Silk

Long before national boundaries were fully established, cross-cultural trade was ubiquitous, and portable objects were active agents in ensuring the spread of religions, ideas, and materials across wide geographies. For example, the reader of a thirteenth-century Gospel book made in Nicaea would have lifted a silk veil to reveal the radiant miniature icon (devotional image) showing the transfigured Christ, who radiates light. The veil has been removed for conservation reasons, but the sewing string can still be seen perforating the top of the page shown below.

The Transfiguration, 1200s, unknown illuminator, made in Nicaea or Nicomedia. From a Gospel Book. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 8 1/8 × 5 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig II 5, fols. 236v–237. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Sericulture (silk production) was introduced to the eastern Roman Empire, known as Byzantium, through silkworm eggs from China or central Asia during the reign of Emperor Justinian (A.D. 527–565). The cities of Nicaea and Constantinople became great silk-weaving centers between Europe and Asia. Silk was so precious in the Byzantine world that it was not only worn as an elite status symbol, but was also used to enshroud reliquaries, altars, and manuscripts.

Armenian Book Arts

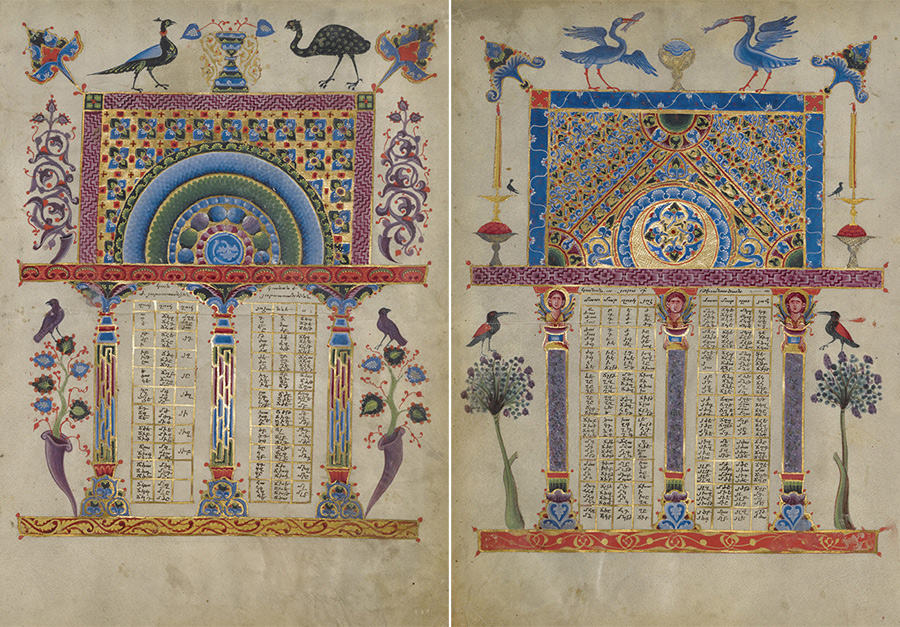

During the long history of the Silk Road, Armenian merchants emerged as major players on the stage of silk trade, regulation, and production. The stunning, prismatic pages below were once part of a Gospel book made for Constantine I, Catholicos (Patriarch, 1221–67) of the Armenian church in the kingdom of Cilicia in southeast Asia Minor. The commission was given to the esteemed illuminator T’oros Roslin, whose unusual surname—an indication that he was of noble origin—suggests that his parents or ancestors immigrated to Armenia from Western Europe. His art is celebrated for incorporating Byzantine, European, and Chinese motifs and styles, which in turn reflects Armenia’s unique commercial ties between Asia and Europe.

Canon Table Pages, 1256, T’oros Roslin. From the Zeyt’un Gospels. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 10 7/16 x 7 1/2 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 59, fols. 1 and 8. Digital images courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Following Roslin’s example, when the kingdom of Armenia was under Mongol rule, artists in isolated monastic centers around Lake Van began incorporating Chinese dragons and phoenixes into book arts. Some of these precious objects were produced using paper, invented in China during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.) and which likely arrived in Asia Minor and Europe through trade networks with cities like Tabriz (Iran), Baghdad (Iraq), and elsewhere in the vast Islamic world.

A Love for Porcelain

The Christian kingdoms of Eurasia exchanged goods, technology, knowledge, and beliefs with the many Muslim principalities that spanned from the Iberian Peninsula across north Africa to Central Asia. In fact, artists often imagined the three kings who brought gifts to the Christ Child as rulers from Europe, Africa, and Asia, based on their dress and physiognomy. One of the most iconic examples of this back-and-forth influence is the blue-and-white ceramic vessel seen in Andrea Mantegna’s intimate painting.

The Adoration of the Magi, about 1495–1505, Andrea Mantegna. Distemper on linen, 19 1/8 × 25 13/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.PA.417. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Early Chinese porcelain relied on the mineral cobalt from Persia to produce the brilliant blue that is now most often associated with Chinaware. Certain shapes and designs from Persia—such as long-necked and tapered vases—inspired new forms in China. And East Asian decorative patterns (including dragons, phoenixes, and peonies) began appearing on imitation ceramic vessels in cities like Tabriz and Iznik.

The blue-and-white cup in Mantegna’s painting is recognizably Chinese, similar to those export wares produced at the imperial factory in Jingdezhen during the Yongle reign (1404–24). Aristocrats in Europe received porcelain goods as early as the fourteenth century, and during Mantegna’s lifetime, Lorenzo de’ Medici in Florence and Isabella d’Este in Mantua (one of his primary patrons) received major gifts of this “white gold,” as it was called.

European Ceramic Arts

A dish in the Getty Museum’s collection highlights the transcontinental and transoceanic exchange between Europe, the Ottoman and Persian Empires, and China. A merchant ship (likely Portuguese), set within interlocking ogival quatrefoils found in Islamic art and architecture, is surrounded by meander vines and peony blossoms typical of Chinese porcelain. This conscious borrowing of Indo-Islamic and East Asian motifs and patterns typifies imitation alla porcellana tin-glazed earthenware in Europe.

Blue and White Dish with a Merchant Ship, about 1510, unknown artist, made in Cafaggiolo, Italy. Tin-glazed earthenware, 9 9/16 in. diam. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.DE.109. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, workshops across the Mediterranean were producing blue-and-white objects, so much so that these luxury items became associated with the cities of Valencia, Genoa, Cafaggiolo, Florence, Delft, Iznik, and the Island of Mallorca. China was truly at the center of this production, even if only as a distant influence or historical antecedent.

Inspired by classical Chinese painting on scrolls, a creative merging of style and media evolved from East to West as Chinese and Japanese potters in the 1600s decorated vases with atmospheric landscapes. The scene on the blue and white lidded bowl (on the right in the pair below) shows a mountainscape of jagged rock cliffs, temples, and foliage blanketed in mist. The elaborate gilt-bronze mounts, added a few years later to suit European taste, completely transform a practical object into a collectible, decorative one to be treasured as an object of rarity and luxury.

Pair of Lidded Bowls, porcelain, about 1650–80, made in Japan or China; mounts, about 1680, attributed to Wolfgang Howzer. Hard-paste porcelain, underglaze blue decoration with gilt-metal mounts, each 13 9/16 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.DI.178. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

China, Imagined

The French court’s fascination with the perceived exoticism of the Far East inspired an imaginative depiction of the daily life of emperor Shun Chi in the popular tapestry series The History of the Emperor of China. In this tapestry, La Collation, the royal couple enjoys a light repast while being entertained on the grounds of an imagined imperial summer palace.

The Collation from The Story of the Emperor of China series, design after Guy-Louis Vernansal, Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer,

and Jean-Baptiste Belin de Fontenay; woven at the Beauvais Manufactory, about 1697–1705. Wool and silk, 122 × 166 1/2 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.DD.336. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

The French weavers used popular motifs to evoke China, such as the imperial insignia of a winged dragon on the crest rail of the high-backed chair that was reserved for the exclusive use of the emperor. They also included ceremonial guardian dragons at the corners of the colorful, ceramic-tiled roof of the fanciful pavilion. The emperor wears a fur-trimmed red cap set with peacock feathers and a blue robe decorated with stylized cloud or wave forms. Blue-and-white porcelain vessels, exported from the imperial workshops, are shown on a European-style sideboard.

The Vogue for Chinoiserie

This paneled room of mid-18th-century décor is a Gesamtkunstwerk—a total work of art with carved and gilded panels, overdoor paintings, elegant and ornate furniture, small sculptures, and a folding screen. The ornamental mirrors are placed strategically opposite each other to both amplify candlelight and create enfilade, mimicking the rows of rooms in grand 18th-century homes that were designed to draw the visitor from one room to the next.

Paneled Room, about 1755, French. Painted and gilded oak; four oil-on-canvas overdoor paintings; breche d’Alep mantelpiece; modern mirrored glass; gilt-bronze hardware, 23 ft. 6 1/2 in. × 25 ft. 6 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 73.DH.107. All rights reserved

The commerce of objects and images was critical to the exchange between East and West, and rare commodities such as porcelain, lacquer, and textiles flooded into Amsterdam, London, and Paris. This paneled room exemplifies the European vogue for all things Chinese, which reached its height at the court of Louis XV. The curves of the porcelain and the metalwork echo the decorative motifs of the rococo interior.

Among the many examples of chinoiserie on display in this room is an inkstand created by French craftsmen, who added a red lacquered base and gilt-bronze mounts to a pair of Chinese porcelain wine cups and figures. This European assemblage transforms the two outer cups into an inkwell and a sand shaker. The central cup once held a sponge for wiping the pen nib. In the 1700s and earlier, the writer would have sprinkled sand on wet ink to speed drying.

Power and Belief

The cave temples of Dunhuang originally served as refuges and remembrances, places for both shelter and devotion. Meditations and offerings filled the spaces, and Dunhuang’s status as a prominent pilgrimage site extended for hundreds of years. As the Silk Road declined in the late fourteenth century, however, the caves slowly fell into disuse, and the great site was all but forgotten until it was rediscovered in the late nineteenth century.

Interior of Cave 285 at Mogao, Western Wei dynasty (535–556 CE). Image © The Dunhuang Academy. All rights reserved

In many ways, the caves’ ebb and flow of function and meaning parallels the story of each of these objects. Artworks are not static objects. Cultural context shades and informs our understandings over time, particularly of objects that portray power and belief. Creating, owning, using, venerating, and preserving these objects establish lines of connection across times, cultures, and ourselves as viewers.

Encountering these objects brings our individual beliefs into a shared space, a collective melding of belief, place, and time. Combining historical narratives, visual observation, and personal experience, each visitor has the opportunity to reflect on the meanings these objects hold.

Through our gallery course, the three of us (curator Bryan Keene and educators Christine Spier and Andrew Westover) look forward to joining with you in this process, fostering inquiry and critical discourse as we consider multiple understandings of these incredible objects.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.