Initial D: A Skull from Gualenghi-d’Este Hours, Taddeo Crivelli, about 1469. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 13, fol. 106

I cannot imagine a single day without art.

Art enriches our lives and feeds our innate quest for the beautiful and the imaginative. It evokes love, loss, anger, discomfort, emptiness, longing, and empathy. Art has the power to bring people together and drive them apart. Experiencing art can be an individual act or a communal one, each powerful in different ways.

December 1 has come to be known among art and AIDS organizations as Day With(out) Art. Now in its 25th year, Day With(out) Art is a call to action against the AIDS pandemic and its devastating effect on art and culture. As a curator of manuscripts, this day prompts me to reflect on the enduring relevance of centuries-old images in our collection, ones that reveal and celebrate the vulnerability of the human condition. Though the collection is centered on Christian art of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, it contains themes that resonate far beyond belief, time, and place.

Loss and Survival

Like people, artworks endure—and sometimes succumb to—pandemics, disasters, and wars. Museums preserve the survivors. Archives and libraries (such as the Getty Research Institute) both deepen our appreciation of what remains and help us piece together the histories of what does not.

The Ascension of Christ from the Laudario of Sant’Agnese, Pacino di Bonaguida, about 1340. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 80a, verso

The story of this exquisite page depicting The Ascension of Christ is one of loss and survival. It was illuminated by an artist associated with the workshop of painter-illuminator Pacino di Bonaguida, one of many artists who appears to have died from the 14th-century outbreak of bubonic plague known as the Black Death. This epidemic’s indiscriminate toll on life across Europe is not unlike the sting of death inflicted by AIDS across the world today. In the miniature, the faithful gaze in wonder as the newly resurrected Christ ascends into heaven, an image that would have been particularly poignant in the wake of the human devastation caused by the plague.

This single leaf is one of three in the Getty’s collection that once formed part of a book of songs of praise called the Laudario of Sant’Agnese. A group of wealthy laymen and women in Florence commissioned this luxurious manuscript in the years leading up to the Black Death of 1348. Later in history, as part of 19th-century collecting practices, the laudario was disbound and individual leaves sold to private collectors who prized such masterpieces in miniature. Despite the many twists and vicissitudes of history, we are fortunate to know the work of Pacino’s collaborators on the Laudario of Sant’Agnese through 31 leaves, cuttings, and fragments from the manuscript now housed in 19 collections across Europe and the United States. This single book, though damaged and dispersed, has endured across eight centuries.

The Fragility of Life

Loss of life was an ever-present reality in the long Middle Ages, and death was at the forefront of the medieval mind. The devout recited daily prayers to commemorate the souls of the deceased and to prepare their own minds, bodies, and spirits for the inevitable and impending death. Additional masses were often said in memory of the dead on Mondays.

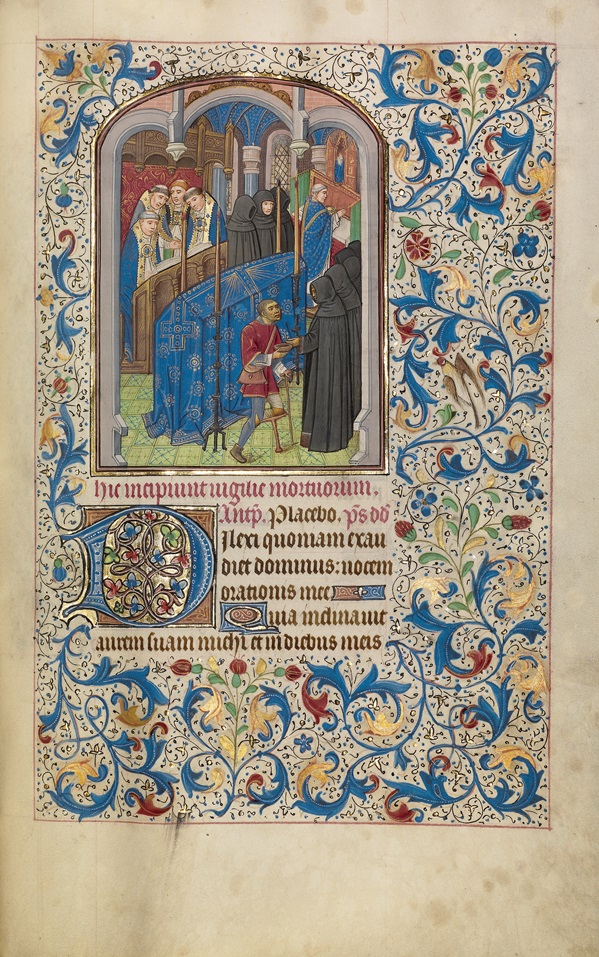

Mass of the Dead in a Book of Hours, Willem Vrelant, early 1460s. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 8, fol. 189

This illumination from a medieval prayer book employs a burial scene to remind us, the living, of our own fragility. Candles flank a casket draped in blue cloth woven with golden sunbursts and a cross pattern as the officiant (at top right) prepares to lead the Office of the Dead. Tonsured clerics sing from a choir book and hooded monks or friars gather in solemnity, one offering alms to a crippled man. Even as the dead are remembered, so too are the suffering who yet live. The pages that follow discuss the virtues of compassion and charity, which grow from our connection to the humanity of others and ourselves.

The text for the Office of the Dead in this manuscript comes from Psalm 114 and includes beautiful sentiments about receiving aid from the divine, deliverance from the sorrows and tribulations of death, and eternal rest and perpetual light. The initial D at the top of this post by artist Taddeo Crivelli begins the same passage, with the skull serving as a memento mori, a reminder of the fleeting nature of life.

Death comes for us all. How generously do we choose to live with the time we are given?

Love, The Universal Virtue

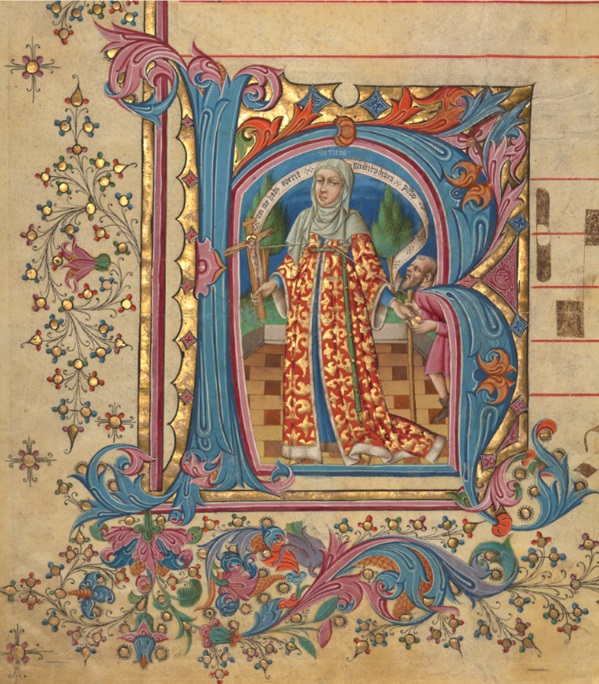

Initial K: Caritas from a gradual, Master of the Cypresses (Pedro de Toledo?), about 1430–40. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 15, verso

Which is greater, love or belief? Once part of a large choir book, this initial K contains an allegory of charity that suggests one answer. A well-dressed women, identified as Caritas (Charity), holds a crucifix in one hand and gives a gold coin to a poor man with the other. A scroll with texts billows around the figure and reads (in Latin), “Whoever has me [Charity] covers a multitude of sins.”

Charity is often synonymous with love, and Christ’s sacrifice on the cross was considered the ultimate act of love for humankind. Thus it is appropriate that the illuminator drew lines physically linking the wound in Christ’s side with Caritas’s heart and the poor man’s staff. The author of I Corinthians 13:13 wrote that charity (or love) is the greatest virtue among faith, hope, and charity, a statement as relevant today as when this manuscript was illuminated over 500 years ago. Indeed, it is worth repeating and truly considering the implications of the phrase contained on this miniature: “Whoever has charity or love covers a multitude of sins.” Love is a universal virtue to be championed above all dogmas, stigmas, and other divisive beliefs.

Initial K: Caritas (detail) from a gradual, Master of the Cypresses (Pedro de Toledo?), about 1430–40. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 15, verso

Sorrow and Empathy

Medieval viewers were especially accustomed to meditating upon images of sorrow and suffering, subjects most of us seem anxious to avoid.

One of the most startling and moving representations of individual agony in medieval art is the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin, which depicts moments of pain and loss from the Virgin’s life with Christ. In the Seven Sorrows below, illuminator Simon Bening depicts the Virgin Mary in an act of quiet but longing meditation, surrounded by seven swords aimed at her heart. Each sword corresponds to a scene in the miniature’s frame: the moment when Jesus was circumcised, when the Holy Family fled to Egypt to protect the newborn infant, when Mary and Joseph lost the young Jesus in the temple, when Christ carried the cross to Calvary and his subsequent crucifixion, the time of mourning after his death, and his entombment.

The texts accompanying the image in this book directed the thoughts and emotions of a medieval reader-viewer to the pain Mary felt at each stage in her son’s life. Part of the human condition is to empathize cognitively, emotionally, or compassionately with those around us during times of sorrow and joy. Here we see art as a powerful vehicle for fostering a sense of shared experience, engendering mutual respect, and inspiring a new perspective.

The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin from Prayer Book of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg, Simon Bening, about 1525–30. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 251v

Anonymity

Time’s power over art extends beyond physical destruction to the erasure of identity. Within the pages of many manuscripts at the Getty are stunning miniatures by artists whose names have been lost. Attributing a work of art to a specific artist can be complicated—particularly in the case of manuscripts, which were often created through collaboration (This was the case for artists working in the orbit of Pacino di Bonaguida or Taddeo Crivelli, both of whom we encountered earlier). Far fewer works of art were signed in the Middle Ages than in the modern period, and archival sources are rarely complete or comprehensive.

Saint Jerome in Epistles, Master of the Getty Epistles, about 1528–30. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig I 15, fols. 1v–2

Art historians have sometimes assigned monikers to elusive artistic personalities whose hands can be recognized, even as their names remain unknown. The so-called “Master of the Dominican Effigies,” for example, takes his name from a panel painting in Florence of Dominican saints and blessed figures. A painter-illuminator, this artist appears to have collaborated frequently with others from the orbit of Pacino di Bonaguida. In fact, he contributed to the Laudario of Sant’Agnese, the disbound book described earlier.

Other anonymous artists, like the Master of the Cypresses, are often associated with known and documented artists, Pedro de Toledo in this case. Still others, like the Master of the Getty Epistles, are named after the best representative work in their particular style. In the detail below, we can marvel at the precision of the artist’s rendering of landscape, perspective, and volume, and be moved by Saint Jerome’s act of piety, having flogged himself and beaten his chest with a stone in imitation of Christ’s suffering. The illuminator even rendered blood lines and bruises on Christ’s tiny body on the crucifix.

Saint Jerome (detail) in Epistles, Master of the Getty Epistles, about 1528–30. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig I 15, fol. 1v

There are about sixty of these “masters” in the Getty collection, and as a group, they represent a history of manuscript illumination that could rival (or surpass) even the greatest masterpieces by named artists. The litany that follows enumerates each of these anonymous artists, whose lives have been lost to time and pieced together by generations of scholars. Although these artists lived long before the AIDS crisis, their work is an important part of our shared cultural heritage, despite the fact that their identities remain unknown.

Day With(out) Art is a time of remembrance and celebration of the artistic and cultural contributions of all individuals, all communities. I think it is a fitting day to commemorate people whose lives make a difference, ensuring that no name is lost to history.

† Master of the Ingeborg Psalter

(active: about 1195–about 1210, France)

† Bute Master

(active: about 1260–90, France and Flanders)

† Bolognese Illuminator of the First Style

(active: about 1260s, Bologna)

† Master of Gerona

(active: about 1260–about 1290, Bologna)

† Master of the Dominican Effigies

(active: about 1325–about 1350, Florence)

† Master of Jean de Mandeville

(active: 1350–70, France)

† Court Atelier of Duke Ludwig I of Liegnitz and Brieg

(active: about 1353, Poland)

† Virgil Master

(active: about 1380–about 1420, Paris)

† First Master of the Bible Historiale of Jean de Berry

(active: about 1390–about 1400, France)

† Master of the Brussels Initials

(active: about 1390–about 1410, Paris and Bologna)

† Master of St. Veronica

(active: about 1395–about 1415, Germany)

† Novella Master

(active: about 1396–1410, Padua)

† Master of the Golden Bull

(active: about 1400–1405, Prague)

† Boucicaut Master

(active: about 1400–about 1430, France)

† Master of Dirc van Delf

(active: about 1400–about 1410, The Netherlands)

† Master of Trinity College Ms. B.11.7

(active: about 1400–about 1430, England)

† Egerton Master

(active: 1405–20, Paris)

† Rohan Master

(active: 1410–40, France)

† Spitz Master

(active: about 1415–about 1425, France)

† Master of Guillebert de Mets

(active: about 1415–60, The Netherlands)

† Master of Sir John Fastolf

(active: 1420–60, France)

† Olivetan Master

(active: about 1425–about 1450, Milan)

† Master of the Murano Gradual

(active: about 1430–about 1460, Lombardy and the Veneto)

† Chief Associate of the Bedford Master

(active: about 1430–65, France)

† Master of the OXford Hours

(active: about 1440s, France)

† Master of Wauquelin’s Alexander

(active: about 1440–about 1460, Bruges)

† Master of Jean Chevrot

(active: about 1440–about 1460, probably Bruges)

† Master of Jean Rolin II

(active: about 1440–about 1465, France)

† Master of the Antiphonary Q of San Giorgio Maggiore

(active: about 1440–about 1470, Northern Italy)

† Master of the Osservanza

(active: about 1440–about 1480, Siena)

† Master of the Geneva Boccaccio

(active: about 1445–70)

† Master of the Llangattock Hours

(active: about 1450–about 1460, probably Bruges)

† Master of the Llangattock Epiphany

(active: about 1450–about 1460, Bruges)

† Master of the Lee Hours

(active: about 1450–about 1470, The Netherlands)

† Master of the Jardin de vertuese consolation

(active: 1450–75, The Netherlands)

† Coëtivy Master

(active: about 1450–about 1485, France)

† Master of the Birago Hours

(active: about 1460–about 1480, Lombardy)

† Master of the Brussels Romuléon

(active: about 1465, The Netherlands)

† Master of the Dresden Prayer Book

(active: about 1465–about 1515, The Netherlands)

† Master of Mary of Burgundy

(active: 1469–83, The Netherlands)

† Vienna Master of Mary of Burgundy

(active: about 1470–about 1480, Bruges)

† Master of Edward IV

(about 1470–about 1500, Bruges)

† Master of the Soane Josephus

(active: about 1475–about 1485, probably Bruges)

† Master of the Getty Froissart

(active: about 1475–about 1485, Bruges)

† Master of the First Prayer Book of Maximilian

(active: about 1475–about 1520, Ghent)

† Master of the Houghton Miniatures

(active: about 1476–about 1480, perhaps Ghent)

† Master of the Copenhagen Caesar

(active: about 1480, probably Bruges)

† Master of the White Inscriptions

(active: about 1480–about 1490, Belgium)

† Master of Cardinal Bourbon

(active: about 1480–1500, France)

† Master of Jacques de Besançon

(active: about 1480–1500, France)

† Master of James IV of Scotland

(active: about 1485–about 1530, perhaps Ghent)

† Master of the Prayer Books of around 1500

(active: about 1485–about 1520, Bruges)

† Master of the Lübeck Bible

(active: about 1485–about 1520, perhaps Ghent)

† Master B.F.

(active: about 1495–1510, Lombardy)

† Master of the Chronique scandaleuse

(active: about 1493–1510, Paris)

† Master of the Getty Epistles

(active: about 1528–about 1549, French)

_______

Inhabited Initial B in a breviary, 1153. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 1, fol. 140v

While preparing to write this post, I stumbled upon a poignant red ribbon—similar to the AIDS ribbon—as part of an interlace initial B in a manuscript illuminated by an unknown, and still-unnamed artist. Knotwork and interlace patterns in medieval art are at times interpreted as guides for meditation or as repellents of evil. Either association finds its parallel in the meaning of the AIDS ribbon.

I thank Elizabeth Morrison, Annelisa Stephan, Rheagan Martin, Andrew Westover, and especially Mark Mark Botieff for sharing thoughts that helped shape this post.

Comments on this post are now closed.