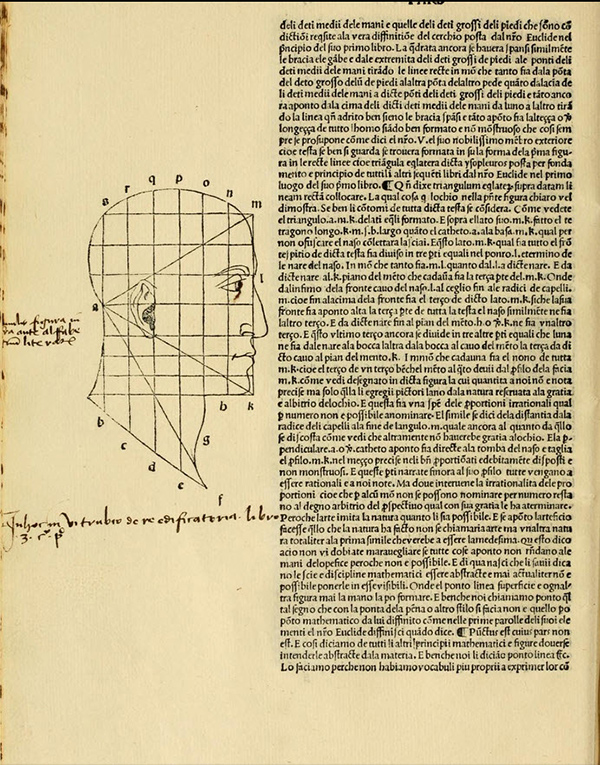

Woodcut in Divina proportione, 1509, Luca Pacioli. The Getty Research Institute, 84-B9582. See full digitized book

In the 15th century, a new form of mass communication dramatically and permanently changed western society: the printed book. The invention of the printing press with movable metal type enabled texts to be printed faster and more cheaply, enabling knowledge and information to be disseminated more widely than ever before.

During the European Renaissance, from the 14th through the 17th centuries, there was renewed interest in the classical world and its knowledge. Scholars turned to literature, philosophy, art, music, politics, science, religion, and other fields of intellectual inquiry. Many books were published in Latin or Greek, and many more in vernacular (spoken) languages such as Italian, French, and German, which widened the readership and the promotion of Renaissance ideas. By 1501, with 100 million people on the European continent, there were 250 printing centers that produced 27,000 known titles totaling 10 million books.

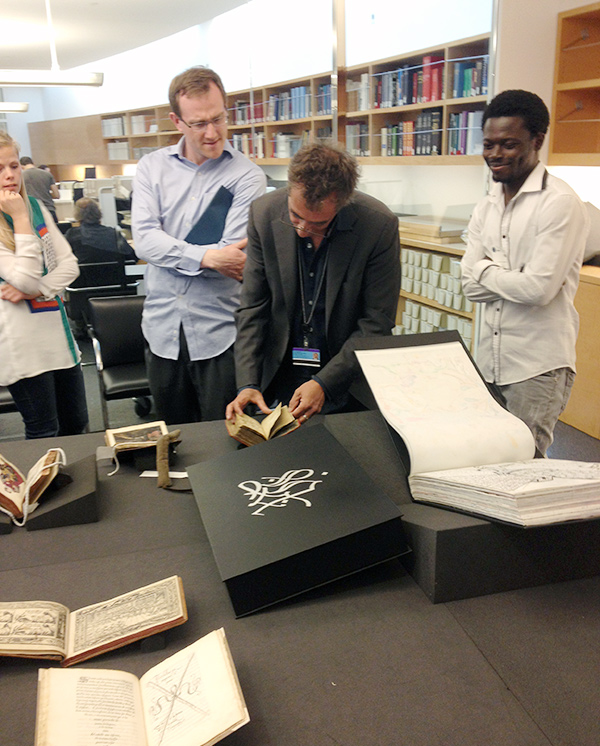

Learning about these developments and how some of them relate to our contemporary world was part of the fascinating week I spent attending “The Renaissance Book, 1400-1650” at UCLA’s California Rare Book School. The course took us from the classroom to the “field,” where we visited three Southern California libraries to view books: UCLA, The Huntington, and our library here at the Getty. Here are a few highlights of what we learned.

Course participants explore volumes from the Getty Research Institute collection with rare books curator David Brafman (center)

Technology

For centuries before the Renaissance, books were written by hand, known as manuscripts. As early as A.D. 200, woodblock printing was used in China; the earliest known moveable type printing system emerged in A.D. 1040 and used ceramic type. Both ceramic and metal type were used in Korea as early as the 1200s.

Around 1450 in the town of Mainz in Germany, Johannes Gutenberg invented the mechanical printing press with moveable metal type. A goldsmith by trade, Gutenberg was inspired by presses used for making wine and olive oil. The first book he printed was the Gutenberg bible, which at over 500 years old is still one of the most renowned and costly printed books. Only 49 copies are known to exist today, of which 21 are complete.

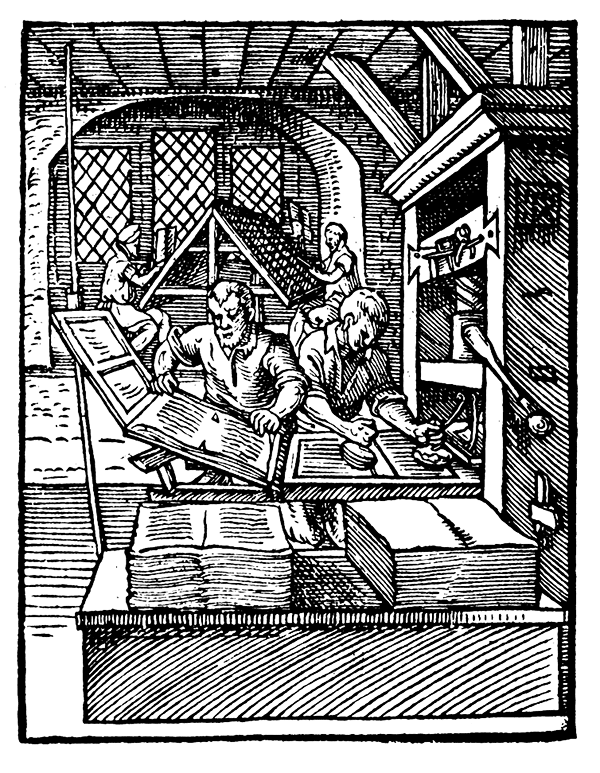

A 16th-century print shop. A “puller” removes a printed sheet from the press, while a “beater” inks type. Source

Here’s how a single page was made in Gutenberg’s press:

- Paper was most commonly made from cotton rags from old scraps of clothing.

- Metal letters (“punches”) were created by casting metal into molds. The type was set by person called a compositor who sat in front of a case of letters and arranged the type into words. For ease and efficiency, the letters we know today as “upper case” were housed in the case above, while the “lower case” were housed in the case below.

- Once a page of type was set, the machine press was operated by two people. One person positioned the paper, while the other applied ink to the type with ink balls.

- A person called the “puller” applied muscle power to turn a lever that moved the paper through the press, impressing it with ink.

Here’s a short demonstration of positioning the paper and pulling the press:

Upper and lowercase type in the Colonial Williamsburg print shop. Photo: Flickr user Maggie McCain, CC BY 2.0

Typography

Renaissance typefaces used in printing were inspired by the scripts used in manuscripts (handwritten books). Humanist minuscule, for example, is a lowercase handwriting style developed by Italian scholar Poggio Bracciolini at the beginning of the 15th century. It was based on Carolingian minuscule that was thought at the time to be from ancient Rome, but is in fact from centuries later, about A.D. 800 to 1200.

Humanist minuscule was the basis for the “Roman” typeface. Roman fonts are still familiar to us today. Garamond, a type of roman font probably available in your computer’s word-processing software, was invented by French 16th-century type designer Claude Garamond.

Ligature of long S and i in 12-point Garamond. Photo: Daniel Ullrich, CC BY-SA 3.0

The familiar italic type that we use on a daily basis today was also invented in the Renaissance. Based on the sloping calligraphic handwriting of Florentine Niccole de Niccoli in the 15th century, the italic typeface for printing was designed by punch cutter Francesco Griffo for the prominent Venetian publisher and printer Aldus Manutius, founder of the Aldine Press. The italic font allowed for faster and cheaper printing, because it saved time and space on the page.

In 1501 the Aldine Press printed the work of classical poet Virgil, creating the first book in italic type as well as the first octavo, a pocket-sized format much like our contemporary paperback books.

Page from Virgilius, 1501, Aldo Manuzio and Andreas Torresanus de Asula. Reproduced courtesy of the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze. Image © 2011 ProQuest LLC. Source

The Illustrated Book

Books covered a variety of subject matter in the Renaissance—Latin and Greek classical texts, literature, religion, law, science. While some books were only text, others included illustrations, too. The text was printed first, and then illustrations were applied by hand or added through another printing.

A few examples are shown below.

Manual for drawing proportions:

Design by Leonardo da Vinci in Divina proportione, 1509, Luca Pacioli. The Getty Research Institute, 84-B9582. See full digitized book

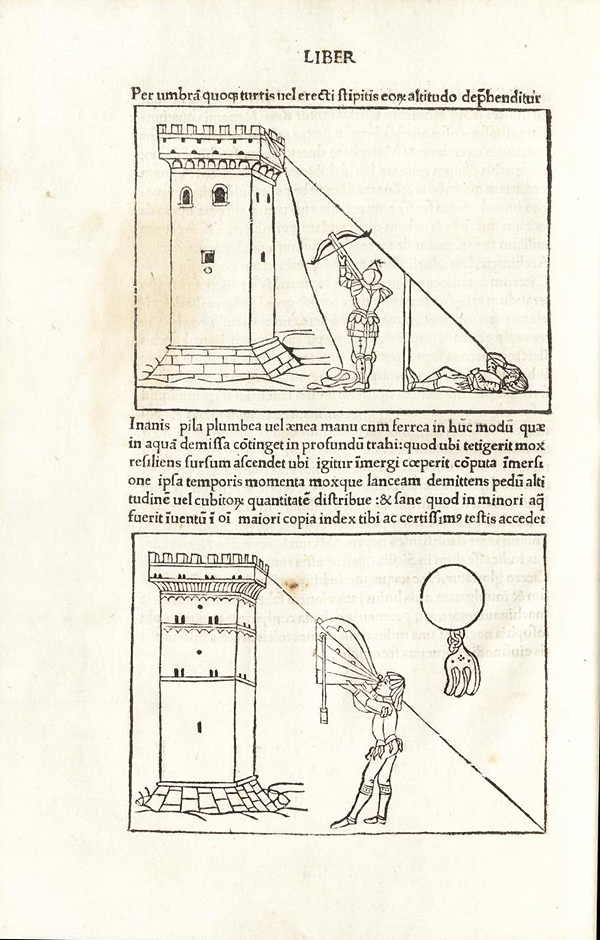

Explanation of military technology:

Woodcut in De re militari, 1483, Roberto Valturio. The Getty Research Institute, 86-B27137. Full digitized book

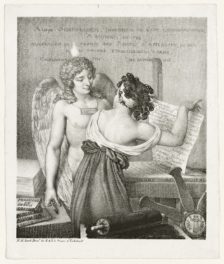

Allegorical illustration in an emblem book

Woodcut in Emblematum liber, 1534, Andrea Alciati. The Getty Research Institute, 84-B21465. See full digitized book

Social Capital

Most Renaissance books were sold as unbound sheets of paper. The purchaser would have these bound to suit their taste. Books with high-quality leather and embellishments would certainly show off a person’s wealth. A binding of simple vellum—animal skin soaked in water and calcium hydroxide and then stretched—would have been used for educational or instructional texts, such as those frequently thumbed by students and professors.

Ornamented leather cover of Champfleury…, 1529, Geoffroy Tory. The Getty Research Institute, 84-B7072. See full digitized book

Plain vellum cover of De re militari, 1483, Roberto Valturio. The Getty Research Institute, 86-B27137. See full digitized book

Books were also purchased entirely blank. Owners would share the book with their circle of friends, who would add drawings or handwritten notes. Such a book, called a liber amicorum (book of friends), was like a Renaissance Facebook used to advertise a person’s social network. The tradition of this type of book was revived by the Getty Research Institute in 2012 with an artist’s book project, the LA Liber Amicorum.

Page in Liber amicorum, 1602–12, Johann Heinrich Gruber. The Getty Research Institute, 870108, leaf 18 verso. See full digitized book

To explore the Renaissance book further, see the recommended reading below.

Further Reading

- The Book in the Renaissance by Andrew Pettegree (2010)

- The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe by Elizabeth Eisenstein (1979)

- The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making by Adrian Johns (1998)

- The Coming of the Book: The Impact of the Book 1450–1800 by Lucien Lefebvre and Henri Jean Martin (1976)

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks