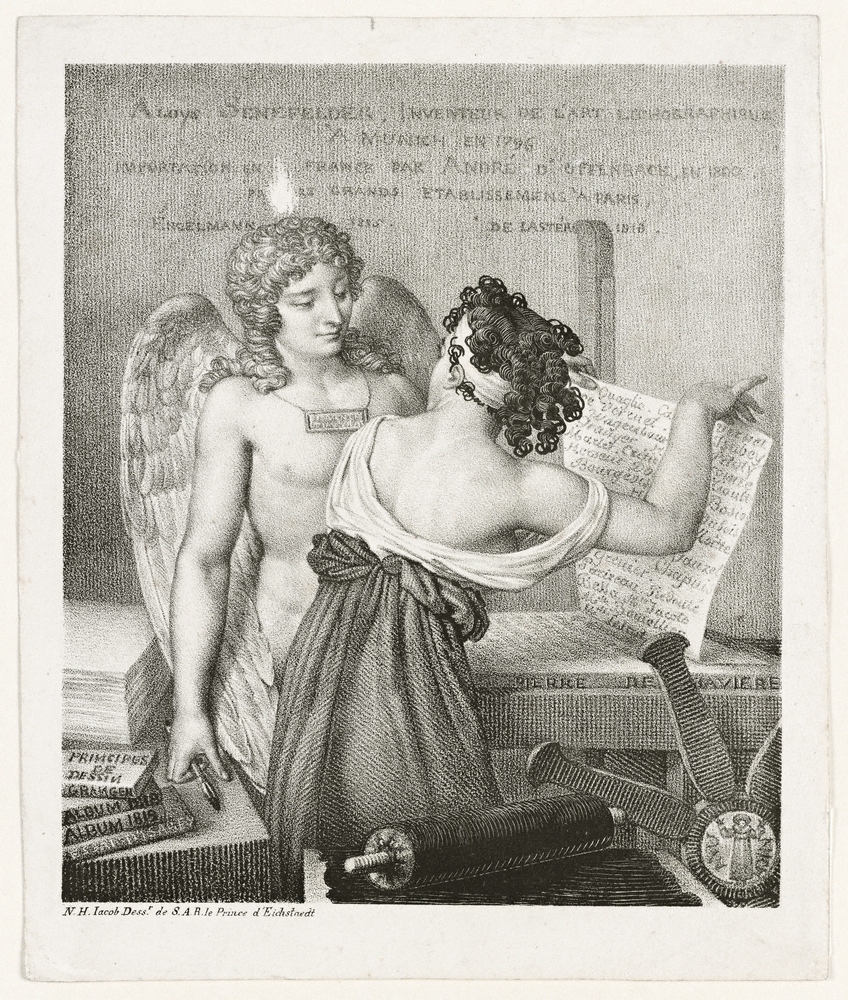

The Genius of Lithography, 1819, Nicolas Henri Jacob (French, 1781–1871), lithographer. Lithograph, 19.2 x 16.4 cm (sheet 22 x 18.4 cm). Originally published in Alois Senefelder, L’art de la lithographie (Munich, 1819). The Getty Research Institute, 2014.PR.8

Necessity may be the mother of all invention, but genius certainly plays a part. French printmaker, painter, and draftsman Nicolas-Henri Jacob’s print The Genius of Lithography (1819) is an ode to a remarkable invention fired by a stroke of genius.

It celebrates the inventor of lithography, Alois Senefelder, a German actor and playwright who developed the technique in the late 1700s not in the service of art, but as a new, cheaper method for printing his plays. Created using the very technique it celebrates, The Genius of Lithography recently entered the Getty Research Institute’s collection, complementing its strong holdings of 19th-century treatises on printmaking.

The Eureka Moment

The story of lithography’s invention is an unusual one. Faced with debt and unable afford the printing of his latest play, Alois Senefelder started experimenting with new methods to publish his theatrical works. Eventually the playwright-turned-innovator hit on a process he called “stone printing.” Using limestone from his native Bavaria, Senefelder prepared the surface of his stone so text or image would accept ink and the blank areas would repel ink. Once the stone had been properly prepared and inked, the image could be transferred from stone to paper with a lithographic printing press.

Unlike engraving and etching, which require great technical knowledge, Senefelder’s technique allowed artists with no printmaking skills to create works by simply drawing with a pen. Lithographic specialists would take care of the rest of the production, often transferring the drawing onto the stone itself. Senefelder’s stone-printing method eventually became known under the French name lithographie, from the Greek for “stone writing.”

Jacob’s Homage

The Genius of Lithography celebrates this discovery by featuring the winged “genius” of lithography—a personification of the inspiration that miraculously visited the indebted playwright—and a young woman, herself perhaps a personification of an artist or printmaker, in the process of printing a lithograph. Together they pull a proof from the press that contains the names of many French and Bavarian practitioners of lithography.

Other clues point to the subject of this composition: the press is labeled “PIERRE DE BAVIERRE” (Stone from Bavaria) and MUNICH—references to Senefelder’s home—while a stack of books on the left includes texts such as Granger’s Principes de dessin, Isabey’s Essais lithographiques, and Albums lithographiques. Senefelder’s name occupies a place of prominence at the top of the print, announcing him as the inventor of the art form.

An Innovator’s Legacy

The creator of the print, Nicolas-Henri Jacob, produced a large body of lithographs over the course of his career; he achieved success as a professor of drawing at the École nationale vétérinaire d’Alfort, a veterinary school in France, and exhibited at the Paris Salon.

The Genius of Lithography was first published in the French edition of Senefelder’s book L’Art de la lithographie in 1819. It’s fitting that Jacob created a lithograph dedicated to the remarkable man who had such an outsized influence on his own artistic career and the history of printmaking itself.

The Genius of Lithography is available to study by qualified researchers. Plans have not yet been made for its display in the galleries.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.