Last month, I gave a presentation with my colleague Tina Shah at the annual Museum Computer Network (MCN) conference in Atlanta about an online collaboration tool for scholars that several of us in the Web group at the Getty have been developing (view our presentation here). The project is experimental, and since we only have a proof of concept working at this point, Tina and I reported on the process of developing the site. We wanted to share what we’ve learned so far with our colleagues working in other museums and archives.

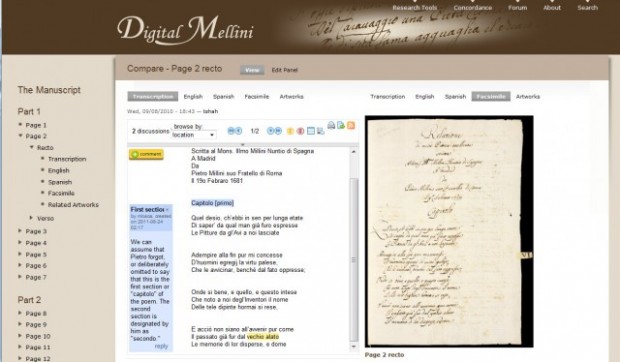

Digital Mellini is an online tool that allows scholars to collaborate with one another by annotating text and associating images with the text.

The idea for the project came from a visiting scholar at the Getty Research Institute, Nuria Rodríguez of the department of art history at the University of Málaga in Spain, and Murtha Baca, head of the Digital Art History Access program at the Research Institute. Nuria and Murtha came to us a year ago with a manuscript and a challenge: Could we create an online tool for art historians and other scholars who want to collaborate on an analysis of the manuscript?

In order to meet the challenge, we’d need to understand how scholars work, learn about textual data encoding standards (we are using the metadata schema TEI), and apply our knowledge of the online world to create a new tool that could be piloted for this manuscript, then rolled out for wider use. We took this challenge as an opportunity for the web group to collaborate on a project with art historians, librarians, and archivists in the GRI.

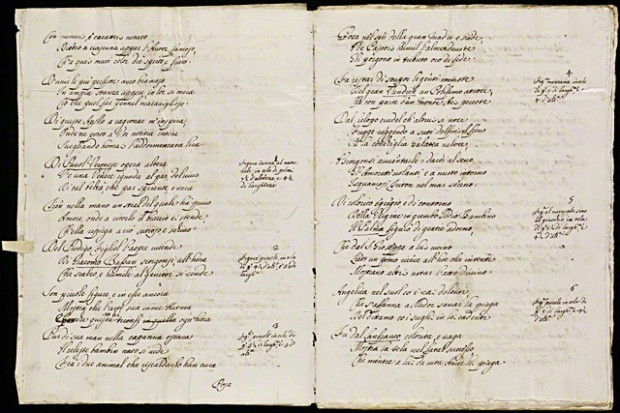

The manuscript that Nuria and Murtha brought to us is in the Research Institute’s collection. It was authored in 1681 by a man named Pietro Mellini; thus the name for our project, Digital Mellini. Mellini’s document is a list of the paintings in his brother’s house. But it’s no ordinary list—Mellini wrote the entire thing in rhyming verse. While art historians often use such lists, called inventories, to track how paintings have changed ownership over the centuries, the format of this inventory provides several challenges. Most notable is the fact that Mellini didn’t name the paintings by title. Instead, he used flowery language to describe the scenes they depict. Thus, scholars must analyze Mellini’s words to identify the paintings.

From this unique manuscript came one of the requests from the scholars: they wanted to comment within the manuscript, even on individual words, having discussions within the text itself.

We had to choose between building a tool from scratch, which would take a lot of time, and adapting existing tools to our needs. Tina did much of the research that led to the decision to use Drupal, a free, open-source content management application. She discovered that Sopinspace, a French company, had released a text annotation module in Drupal, called Co-ment, that allows users to have conversations about words within a text.

In addition to this functionality, the Mellini site will also allow scholars to associate images related to the works described in the poem with the text and provide comparisons with an earlier, more conventional inventory of the Mellini collection. A discussion forum, bibliography, and image gallery will also be part of the tool.

For art historians, working online is often is complicated by copyright restrictions and image fees. Partly for this reason, the collaborative site will only be available to the small group of scholars working on this manuscript. The plan is for scholars to work on the manuscript together, then collaboratively develop analyses that will become the foundation for an online publication about the Mellini manuscript. The tool itself will also be made available for analysis of other historical texts in the field of art history.

The process of working together on this project has been very collaborative itself. Along the way, we’ve learned a lot about the challenges surrounding digital scholarship and online publishing. Many of these challenges are not technology-related at all, but revolve around social behavior and expectations of scholars, who tend to work alone and for whom collaboration can present challenges, as their ideas are also their bread and butter. In fact, several colleagues working in other museums who attended our talk at the MCN conference commented that they are facing similar social challenges around collaboration in their own digital publishing projects.

Increased collaboration has been hailed as one of the effects of our Web 2.0 world by technorati such as Tim O’Reilly and Clay Shirky. Perhaps the stereotype of the lonely scholar who spends hours poring over an ancient text in the library, making notes in pencil, will soon become a thing of the past.

Hye

I am very please that you have this document from my ancestors

I believe that two paintings are now in the Louvre Museum in PARIS

I am FRENCH and i will please to learn more about you

Didier MELLINI

Neat!