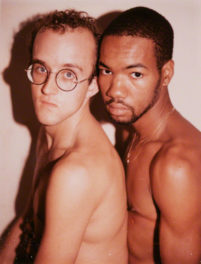

Portrait of a Young Man, Head and Shoulders, Wearing a Cap, attributed to Piero del Pollaiuolo (Italian, 1443–1496), about 1470. Pen and brown ink over black chalk, 14 1/4 x 9 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2012.3. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

I find auctions terrifying. Mesmerizing, but terrifying. When a major early Renaissance portrait drawing came up for auction at Sotheby’s in New York a month ago, my stomach was in my mouth. It was the sort of drawing one hardly ever sees at auction: a very rare, early Florentine portrait drawing of exceptional quality and with a powerful presence.

I had researched it and prepared the bid for several weeks, and now in a few minutes it would all be over—and my work, and that of my colleagues, might be for nothing. My colleagues and I knew of at least three private drawings collectors with infinitely greater resources than the Getty, but the question was whether they would realize the importance of the drawing. To add to the complexity, there were rumors in the market that some of the ink lines of the drawing had been gone over and strengthened at a later date. This would have a substantial impact on its value. We had to assess these rumors to see if they were true. Could they even have been circulated by someone who wanted to buy the drawing cheaply?

I had seen the drawing out of its frame at Sotheby’s in London the previous December, and had been utterly bowled over by the power of it, but could I have missed this problem? We examined the drawing again, and were convinced that all the lines were put there by the original artist.

But who was that artist? Drawings of the period—about 1470, the early Renaissance—are extremely rare, and portrait drawings even more so, which meant that there was little with which to compare it. I spent time researching the attribution, to the Florentine master Piero del Pollaiuolo, and consulting specialists in the field. It seemed credible, although we’ll probably never be absolutely certain who made the drawing. Yet the quality, presence, and rarity of the sheet speak for themselves.

The fine parallel pen hatching is extraordinarily skillful, creating just enough modeling to round the face and delineate the nose, and it gives the image a deceptive simplicity when viewed from a distance. The hair gets texture and tuftiness from thicker pen strokes, while the white of the paper was left entirely blank to convey the whites of the eyes. It’s an incredibly powerful and immediate work of art that pulls you towards it.

For the period, it’s rare. While most surviving drawings from the 1470s are simple, rather scrappy, sketches on small bits of paper, this is a highly finished work drawn on a large sheet, probably made from fine linen fibers. It was likely made as a work of art in its own right, rather than as a preparatory study for a painting. Further, it comes from a period when portraiture was being transformed. Up until the late 1400s, most portraits were made in profile (from a side view) to mimic ancient coins and medals. The new self-awareness that is a hallmark of the Renaissance changed all that, and sitters were increasingly shown full-face, in direct, engaged contact with the viewer. A

So who is this young man that stares out at us from a piece of paper drawn about 540 years ago? There are no inscriptions that identify him, nor other portraits of him known. The felt cap and tunic perhaps identify him as a nobleman, or someone with pretense to be noble. How old do you think he is? Fifteen, twenty, twenty-five? I’d be interested to hear. (By the way, for the wags among you, 540 is not a valid answer.)

His age could be important because of one crucial detail. The buttons on the man’s tunic are on the left side of the collar. As with men’s shirt buttons today, that was unusual for the Renaissance; they would normally be on the right. Combined with the intense observation of the gaze, could this mean that the drawing is a self-portrait of the artist, with the image (and clothes) reversed by the mirror into which he is looking?

At the auction, the bidding moved slowly, and there was much interest in the drawing with at least four different telephone bidders active. But in the end we prevailed. Success! My heart leapt, although I could scarcely believe it was happening. (Being a cautious Brit, I had prepared myself for defeat.)

It was a dream come true, and now this drawing would be on its way to the west coast. Having passed through the centuries in private collections, it had never in its long history been on public exhibition. It goes on display in our galleries tomorrow; please come and see it if you can!

Thanks for making it possible for this intriguing drawing to become part of the collection and bringing us just a hint of what the auction process must feel like. Bravo.

Reminds me of the his brother’s engravings. Also, Mantegna’s. The bags under his eyes make me think he’s in his mid-twenties. But those might just seem more prominent because of the linear medium.

A real-world and affecting overview of the knowledge, research, hopes, dreams and tension involved in the commitment to add just one work of exceptional art to a public collection. Typically, these aspects of acquiring an artwork are absent from the comparatively bland records in printed catalogues which might include title, attribution, date of acquisition, and perhaps price paid. However, when the zeros are forgotten and the relative purchasing power of the amount spent is also lost to memory, a story like Julian’s will still be appreciated because it focuses on the recognition of artistic quality and the human effort made by a curator to secure it for public enjoyment and understanding. Very good essay!

This article definitely whetted my interest in seeing the drawing in person. The note about the buttons is interesting. It always fascinates me how much of the past is shrouded in intriguing mystery only because we don’t know the answers to simple questions.