Throughout 2013, the Getty community participated in a rotation-curation experiment using the Getty Iris, Twitter, and Facebook. Each week a new staff member took the helm of our social media to chat with you directly and share a passion for a specific topic—from museum education to Renaissance art to web development. Getty Voices concluded in February 2014.—Ed.

Back in college I took some aptitude and vocational tests to determine an ideal career. One of the results was detective. “Ha!,” I thought to myself. “That’s totally at odds with my art history major.”

Fast-forward 20+ years, and I spend as much of my time looking through a magnifying glass as a classic detective does—solving the mysteries of the Getty’s Department of Photographs.

As primary cataloguer for the department, I’m responsible for making sure our database is accurate and complete, a ready reference for people who want to access our collection. My goal is to capture as much information as possible about each photograph and record it in our database. At a minimum, I try to determine the photographer, medium, subject or title, date, and location. Sometimes the process is straightforward, and sometimes it is a bit more challenging. Sometimes a photograph is signed, titled and dated, but frequently it is not.

A careful reveal of the backside of an uncatalogued photograph

I follow leads in dozens of directions. I learn something new every day. One day I might be researching Broadway shows of the ‘20s, hoping to recognize an actress, and the next day I might be looking through churches in Florence to identify a particular tomb. Recently I’ve been learning about Britain’s royal family in preparation for an exhibition about Queen Victoria we will be presenting in 2014.

The Getty’s photography collection spans the history of the medium, from Talbot’s photogenic drawings of the 1830s to large digital works made by living artists. We have an amazing number of 19th- and early 20th-century photographs by little-known photographers. I channel my inner sleuth to consult fashion books, the history of automobiles, architectural studies, and more obscure literature to pinpoint the fashion, cars, and buildings that will help me date an image.

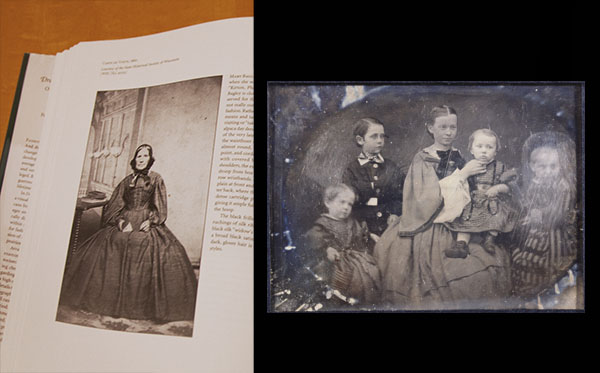

Using fashion history books to help date portraits from the collection

The photographs themselves can be mysteries. “Photograph” is a broad term. The Getty’s collection includes daguerreotypes, salted paper prints, calotypes, albumen silver prints, platinum prints, gelatin silver prints, collotypes, carbon prints, carbro prints, chromogenic prints, inkjet prints, and more. Ten years ago I would have divided photographs into two categories: black and white or color. Now I examine each print to determine the chemical processes used to create the image. Like a detective, I look for clues. How thin is the paper? How large is the print? How glossy is it? Has the image deteriorated? Through a magnifying glass, can I see the paper fibers? Can I see individual drops of ink? When I’m not certain what I’m looking at, the photograph conservators in my department will examine it with a microscope or other tools.

Miriam looks through her handy magnifying glass and light to try to determine the photographic process of this image.

A friend recently thanked me for inspiring him to pursue a museum career. He said that I always made my work sound fun and exciting. I hope that I can convey that enthusiasm to you also.

Connect with more “Be a Photograph Sleuth” content:

- Watch Miriam in real time catalogue a photograph from the Getty Museum collection.

This information is not only fascinating for anyone interested in photography, but also these little known facts about a career path might open the door to someone who loves this art, but is not an artist. The depth of knowledge necessary to fulfill this job with skill and integrity is Miriam’s passion, and we are fortunate to have the Getty where she, along with brilliant curators, enrich this field.

Could a description be given of the education/training one needs to get on a career path to a cool job like this? Thanks.

Great question, Donicia. I have a bachelor’s degree in art history, and a master’s degree in museum studies. I have worked for museums and private art collectors. Through my graduate program I learned a lot about proper handling and storage of art (including photographs) as well as about databases and documentation. I’ve also taken workshops specifically on the history of photography and the identification of photographic media. The sleuthing parts I figure out as I go.

Wow! This was really interesting and enlightening. I never realized what went into cataloguing art including photographs. Thank you so much for sharing what you do. How fortunate for you and the Getty to have found each other. And yes, I agree with the first post, those of us who live in LA are certainly fortunate to have the resources of the Getty and curators like Miriam in our backyard.

What an interesting article. And what an interesting job.

que interesante y bonito es sobre la conservacion de fotografias , como me gustaria llevar cursos sobre estos temas ya que soy un apasionado sobre fotografia del siglo xlx, aunque me falte recursos

gracias miriam

Hello, Gustavo –

Forgive me for replying in English. As I don’t know where you are located, I can’t suggest photographic history resources in your area, but there are a few online that might be of interest. To learn about different photography techniques and how to tell them apart, check out http://www.graphicsatlas.org, which is a project of the Image Permanence Institute. The IPI also has other resources available on their website, http://www.imagepermanenceinstitute.org. To learn more about the history of photographs in the 19th century, I suggest checking http://www.luminous-lint.com, which has thousands of photographer biographies and photograph examples available.

Are you hiring? I think I’d be a good fit.