Throughout 2013, the Getty community participated in a rotation-curation experiment using the Getty Iris, Twitter, and Facebook. Each week a new staff member took the helm of our social media to chat with you directly and share a passion for a specific topic—from museum education to Renaissance art to web development. Getty Voices concluded in February 2014.

When artists die, they sometimes drop out of history. This often happens if the history of their time has not yet been written—or if powerful members of the art world fail to acknowledge their contributions.

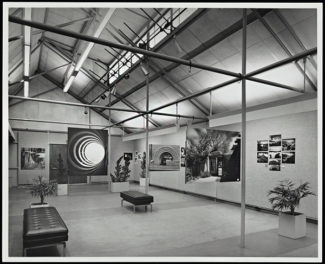

There’s just such a forgotten artist at the center of the exhibition Farewell to Surrealism: The Dyn Circle in Mexico. Visitors often ask how such a fascinating figure, who made paintings pulsing with light and color and edited a unique and influential art journal (Dyn, Greek for “the possible”), could have escaped their attention.

I wondered the same thing when I first came across his paintings in Dyn some three years ago. I remember gazing at them with my colleague Donna Conwell and marveling at their prescience and originality. Like Van Gogh on acid, we said; like a spinning star from Starry Night that had spun out of control and multiplied and expanded to cover a whole canvas. And like Van Gogh also in the colors that seemed to come from the palette of a post-Impressionist, although the forms had a 1960s feel. They were wild in a somewhat conservative way. We had the sensation of having stumbled across someone special.

Donna and I curated the Dyn exhibition out of that generative moment in the Getty Research Institute’s Special Collections reading room, out of our feeling of surprise, even disbelief, that someone so unique could have remained unknown to us for so long, for our whole lives up to that moment. When people ask me why they’ve never heard Dyn’s editor—Austrian painter, thinker, editor, and writer Wolfgang Paalen—I feel we’ve succeeded in our curatorial mission.

But why haven’t we heard of Wolfgang Paalen?

One reason may be that he was not in New York, or even Paris, but in Mexico, a decidedly marginal part of the art world in the 1940s and ‘50s. Nonetheless, he and his colleagues in Mexico had been working toward the same goal as the surrealists exiled in New York, and in 1945, he wrote triumphantly to his fellow painter and friend Gordon Onslow-Ford that “we, and not the people in New York, have found the opening to the new road.”

Wolfgang Paalen with his portrait of André Breton, ca. 1942, photographer unknown. Gelatin silver print, 2 1/2 x 2 1/2 in. Courtesy Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City

He brought his writings, his artistic solutions, and his considerable erudition about First Nations and pre-Columbian culture to New York—primarily in the form of the journal Dyn—but those ideas were gradually appropriated by New York artists. As Amy Winter shows in her book about Paalen, Robert Motherwell, who had worked on Dyn and received, as he put it, his “post-graduate education in surrealism” from Paalen, gradually lost a sense of indebtedness to him. Paalen and Motherwell corresponded frequently, often discussing ideas about art at great length, but now that correspondence is nowhere to be found. Barnett Newman, among others, liberally paraphrased his words in his writings about art, and never gave credit.

Wolfgang Paalen committed suicide in Taxco, Mexico, in 1959. He was depressed, in debt, and threatened with legal consequences for his dealings in pre-Columbian art.

Connect with more “Forgotten Surrealist” content from this week’s Getty Voices, summarized on Storify.

Ms Leddy’s commentary is perceptive, but her insistent mispronunciation of the artist’s name is provincialism at its worst. Paalen contains a long “ah”, not an “ay”. Wolfgang also has the “ah” vowel, but in a short syllable.

Hi John, You are correct, Wolfgang Paalen was Austrian and thus both a’s would be pronounced in German as “ah.” We’ve been using the pronunciation that an American would typically use, which we do in general with artists with foreign names (e.g., Van Gogh). -Annelisa/Iris editor

It is a widely held misconception that the swirling and oscillating vortexes of energy which begin to appear in Wolfgang Paalen’s work in 1940 are attributable to his attempt to “paint the world that physics revealed.” Nor does this striking development in Paalen’s career find its genesis in the most obvious influence of Van Gogh. This monumental shift, which resulted in a body of work now largely regarded as representative of Paalen’s defining and signature style, was in fact the direct result of Paalen’s 1939 visit with Canadian painter Emily Carr (1871-1945) who is today regarded as Canada’s Georgia O’Keeffe. While Paalen was in bustling Paris in 1937 fashioning spooky bat-crowned mannequins, Emily Carr was living in quiet isolation painting the totems of Pacific Northwest Indians and concentric forms of swirling atmospheric energy which in a few years’ time would be themes and strategies adopted wholesale by Paalen, pervasively transforming the course of his art and life. Look at the Emily Carr pictures “A Rushing Sea of Undergrowth” (1932-35), “Above the Gravel Pit” (1937), “Lone Cedar” (1936), “Juice of Life” (1938-39), and “Kispiax Village” (1929). Then consult the 1999 Paalen Catalogue Raisonne and look at the years 1938 through 1941, clearly showing Paalen’s work before and after his life-changing visit with Emily Carr in August of 1939. While this pivotal and redefining association somehow remained under the radar and apparently escaped the attention of Paalen and DYN scholars, Canadian art historians have documented the connection in the 2016 Vancouver Art Gallery exhibition “Emily Carr and Wolfgang Paalen: I Had an Interesting French Artist to See Me This Summer”, which you can read about at the link below. -GRI reader & independent art researcher, Michael Kelley/Kelley Gallery

https://canadianart.ca/reviews/emily-carr-and-wolfgang-paalen/

Part of my first post didn’t make it through: P.S.: Thank you Annette for this fascinating presentation, and thanks to you, Donna Conwell, Dawn Ades, and Rebecca Zamora for your diligent research resulting in the uniformly excellent “Farewell to Surrealism, The DYN Circle in Mexico” exhibition and catalogue. – Michael Kelley