Artworks gathered for repatriation after World War II, ca. 1945–49, Johannes Felbermeyer, photographer. The Getty Research Institute, Felbermeyer photographs for the Central Collecting Point, Munich, 89.P.4 (bx. 73–75), image 173

After four years of work, the Getty Provenance Index® has greatly expanded its database of German art sales catalogs, adding nearly 570,000 records of artwork sales for the years 1900 to 1929. This expansion, adding to existing records for the years 1930 to 1945, gives researchers in provenance and the art market unprecedented information on auction sales in Germany and Austria during the volatile years of the early twentieth century, including the periods of World War I, the Weimar Republic, and the years of politically sanctioned Nazi looting prior to and during World War II.

These half a million new records represent individual auction sales records for paintings, sculptures, drawings, and miniatures recorded in over 8,700 German sales catalogs published between 1900 and 1929. Each record is linked to the full PDF of its corresponding catalog on the website of the Heidelberg University Library.

The new release brings the total number of records of German and Austrian art sales in the Provenance Index to just over 830,000 individual items, all of which can be searched here.

Van Gogh’s Garden in Arles

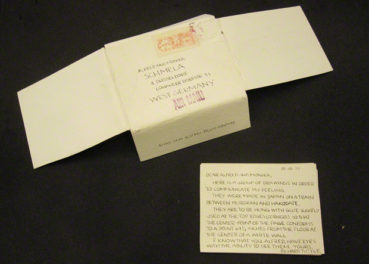

Pages from a catalog of a 1916 art auction held at the Galerie Paul Cassirer in Berlin, held in the Heidelberg University Library. From pages such as these, individual art sales records were digitized and made searchable. Digital images licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0)

As one example of the kinds of records included in the newly expanded German Sales data, let’s look at a World War I–era sale of Vincent van Gogh’s Garden in Arles, which was sadly destroyed in World War II. The painting appears in an auction catalog published by Paul Cassirer and Hugo Helbing for a sale that took place on May 22, 1916, at the Galerie Paul Cassirer in Berlin. The sale was from the collection of the late Julius Stern, a bank director from Berlin, and his wife Malgonie Stern. It was one of many great artworks for sale—including sculptures by Rodin and Maillol and paintings by Renoir and Cézanne—and is emblematic of the type of art that would become ripe for looting in just 20 short years, cast into disgrace by the Nazis as so-called “degenerate” art.

From the information provided in the catalog, we were able to extrapolate information about the painting, the event of the auction, and the catalog as an object unto itself. We then enriched this record with information from Der Kunstmarkt, a periodical that reported on auction sales of the day. From this we find that van Gogh’s Garden in Arles (in German, Garten in Arles) sold at auction for 24,100 marks.

To learn how we digitized events such as this one and made them easily searchable, read on.

Inside the Five-Year Metadata Project

This initiative was once again in partnership with the Heidelberg University Library and the Kunstbibliothek—Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. To process the many records and enable them to be searchable, the collaborative team made small improvements on the processes of digitization, transcription, and database entry set up during phase I of this project.

Our ingestion process began in Heidelberg, where staff identified and scanned catalogs across various European libraries, universities, and institutions, producing high-quality PDFs of these catalogs and generating text files using OCR (optical character recognition). Using Perl code, we then processed these text files into spreadsheets, with data and metadata parsed out into fields. Having learned from our experience with phase I, we knew to expect massive amounts of variety in formats, fonts, and layouts between catalogs (and often even within a single catalog). To mitigate this variation, we used pre-processors to scrub the raw text and format it so that the code could identify various data elements and accurately parse them out into spreadsheets.

This effort did not address the problem of OCR-generated errors in spelling or layout. Rather than dealing with these on the processing end, we allowed spelling errors through to the generated spreadsheets, which were then corrected and augmented one by one by editors contracted for this project.

Snapshot of an Excel spreadsheet used to refine data generated by optical character recognition (OCR). The yellow-highlighted record shows how the sheet formula flagged a misspelling of the German word for canvas.

To help speed up this process, we encoded Excel formulas into our spreadsheets, which track keywords against a lookup table in order to auto-fill related cells in a cascade. As an example, the record highlighted in yellow above has a keyword “Leinwand” (canvas) misread by OCR as “LclnWand.” Here, all the editor needed to do was correct the spelling of the word, and the Excel formula auto-filled in column O, which corresponds with the controlled authority for materials with “auf Leinwand” (on canvas). That keyword then triggered the object-type designation in column N, designating it as a “Gemälde” (painting). This designation further prompted a “YES” in column D, indicating records that contain in-scope material to be published online.

In this example of our process, the yellow-highlighted cell needed to be reviewed by an editor not only to correct the spellings, but also to identify the relationship between two records.

However, not all errors were so simply fixed. The record highlighted in blue above had to be addressed by an editor, due to the phrase “Gegenstück z. Vor.,” or “Counterpart to previous.” In this case, the editor read the previous record for the pertinent information and manually transcribed that information into the cell.

As a final step, all records had to be manually checked for accuracy—it was unwieldy to script for every single eventuality. For example, the formula interpreted a painting on bronze as a sculpture, so the editors needed to manually override this action.

We’ve found great success with these integrated formulas, not only in speeding up the editing process but also in reducing the amount of human error (non-OCR-generated typos, specifically) that comes from producing so much metadata so quickly. Once the preliminary work was completed, editors went back over the spreadsheet and augmented the data with genre and subject designations as well as information often found in the front or back matter of the catalog, such as sellers’ names, estimated or starting prices, and image information.

After all this work was done, the edited data was ingested into our database and further augmented with authority, transaction, and sale price data. Finally, each record was linked to its corresponding PDF hosted on the Heidelberg University Library website, as well as its related bibliographic information in the Getty’s Sales Descriptions database.

Benefits to Researchers

For art market researchers, this expansion of the German Sales Catalogs database will provide a longer perspective on art market shifts and trends during the first half of the twentieth century, a span of years characterized by social upheavals, two great wars, seismic cultural shifts, economic booms, and devastating depressions. Provenance researchers will gain greater context for works of art that were looted or forcefully sold during the turbulent years of the Nazi regime. We are hopeful that this new data will open up more possibilities for scholars in the field and provide further insights for provenance and art market research.

Well done to the team. Thank you for your hard work!!

Does your research help to restore of the paintings and artwork to Rightful owners?