Hiroshi Sugimoto preserves and transforms William Henry Fox Talbot’s 175-year-old “photogenic drawings”

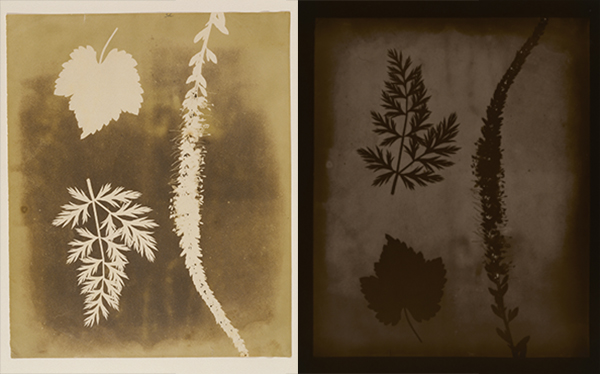

Left: Arrangement of Botanical Specimens, 1838m William Henry Fox Talbot. Photogenic drawing negative, 8 13/16 x 7 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.1002.10. Right: Arrangement of Botanical Specimens, 1839, 2008, Hiroshi Sugimoto. Gelatin silver print, 36 7/8 x 29 1/2 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Gift of the artist, 2013.64.9. © Hiroshi Sugimoto

In 1839 English scientist, historian, and mathematician William Henry Fox Talbot announced an exciting discovery. By coating writing paper with salt and silver nitrate, he had created a light-sensitive surface to capture images of the world, a process he called “the art of photogenic drawing.”

Though less well known today than the daguerreotype, announced just a few weeks earlier that same year, the photogenic drawing “is extremely important to photographic history,” says Arpad Kovacs, curator of the exhibition Hiroshi Sugimoto: Past Tense. “With the photogenic drawing, Talbot invented the negative/positive process—a core concept of photography and one that would become the predominant mode of creating photographs.” Talbot’s discovery, in other words, was one of the greatest breakthroughs in photography until the digital revolution.

Made as experiments, Talbot’s photogenic drawings are extremely fragile and slowly vanishing with age. “He didn’t quite understand how to fix them at first, which is why they’re so prone to fading,” Arpad said, referring to the process of stabilizing an image once the paper has been developed and washed, to stop its sensitivity to light. “It’s interesting to read some of his early correspondence with his friends and relatives, in which he would enclose a photogenic drawing. A few weeks later the images would disappear.”

Ever the tinkerer, Talbot tried fixing his prints using various techniques, including a bath of potassium iodide, which caused the photogenic drawings to fade more slowly, rather than darken over time. Because he was still working out the chemistry, the prints created through these various experiments have all aged differently.

Lacock Abbey, 1835–39, William Henry Fox Talbot. Photogenic drawing negative, 2 15/16 x 3 11/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.1002.32

These fascinating images, their ghostlike forms speaking in a whisper across nearly two centuries, captured the imagination of photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto. He asked the Getty Museum, one of the few museums in the world with a collection of Talbot’s early experiments, if he could see and photograph them. The answer was yes—with one caveat.

Talbot’s photogenic drawings are so fragile and sensitive to light that they needed a stunt double to keep them safe. When Sugimoto visited in 2007, conservators worked with him to create the negatives under low light levels. “They used exact-size replicas of Talbot’s prints to focus the camera and create multiple test exposures,” Arpad explained. “Then, for the final exposure, our conservator placed the actual object briefly in front of the camera. Sugimoto got one take.”

Several of the resulting images are featured in the exhibition Hiroshi Sugimoto: Past Tense, which also includes examples of Sugimoto’s equally enigmatic wax portraits and natural history dioramas. When the artist returned to the Getty Museum in 2014 for the exhibition, director Timothy Potts took the opportunity to ask him about his work and what drew him to Talbot in particular.

“Those negatives are changing, constantly,” Sugimoto says. “Even stored in cool, darkroom storage, [they are] either getting darker and darker or lighter and lighter. Within 50 or 100 years, [they] will be gone. So I felt very responsible, since I noticed this fact.”

Sugimoto’s reimagined Talbot prints are far more than documents of an antiquated technology, however. They are complex works of art in themselves—much larger than the originals, with different color, texture, and tone. Are they photographs of photographs? Or photographs about photographs? The series brings Sugimoto, and us as viewers, into dialogue with the history of photography, a medium that celebrates its 175th birthday this year.

It’s a bold move by any artist, to pay such direct homage to the inventor of his medium. “Sugimoto wants to be as relevant as Talbot,” said Arpad. “And I think he is.”

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks