The real-life tale of the Monuments Men, as told by rare documents in the Getty Research Institute’s special collections

Dr. Frederick Pleasants with the 40,000th picture recovered at the Central Collecting Point in Munich, where Nazi-looted artwork was assembled and redistributed after the war. Photo by Johannes Felbermeyer. The Getty Research Institute, 89.P.4

George Clooney’s new film The Monuments Men tells the story of an international group of approximately 350 men and women—soldiers and scholars, conservators, architects, and artists—who were assembled to protect Europe’s cultural treasures from the destruction of World War II. It is based on two books by Robert M. Edsel, The Monuments Men and Rescuing Da Vinci. As librarians we are thrilled to see not one, but two books about a favored historical period come to life in the new film.

After the war, this dedicated group searched for and rescued priceless art objects stolen from museums and private owners by Hitler’s men and returned the treasures to their rightful owners. In the years following the war, the remaining group of Monuments Men worked under the supervision of the U.S. Department of State, continuing to recover and return more than five million works of art. The work of identifying, recovering, and returning previously lost works continues to this day.

The Central Collecting Point, Munich. Photo by Johannes Felbermeyer. The Getty Research Institute, 89.P.4

The Getty’s collections hold remarkable resources directly relevant to the story of World War II art search and rescue. The special collections of the Getty Research Institute include an extensive collection of WWII-era resources including records of art dealers, inventories of private collections, over 130,000 art-sales catalogs (many of which are annotated with provenance information), and the papers of art historians who were closely involved with arts institutions and the art market during this period. In addition, via our Project for the Study of Collecting and Provenance, the Research Institute is a partner in the German Sales Project, which seeks to document the complex movement of works of art in Nazi-controlled Europe from 1930 to 1945.

The Salt Mine at Altaussee, Austria. Photo by Johannes Felbermeyer. The Getty Research Institute, 89.P.4

Soldier-Scholars

Some of the original Monuments Men are well represented in the Research Institute’s collections, and researchers can find information about their lives and careers before they became Monuments Men, and what they did after the Monuments Men were disbanded in 1946. Their work lives on in our collections—and in a couple of cases, these heroes of art history became directly affiliated with the Getty. Here are some examples:

Douglas Cooper

Art historian and critic Douglas Cooper served first as an ambulance driver, then as an intelligence officer interrogating German prisoners of war, and finally as an investigator of Nazi art-thieves and the dealers who collaborated with them. After the war, he returned to his life as historian and critic, focusing on the Paris School of early Cubism, counting Picasso and other Cubist artists among his close friends. Cooper’s library is heavily annotated with his expertise and provenance information. His library and papers are housed at the Getty.

Otto Wittmann

Monuments Man Otto Wittmann was the director of the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio. Major Wittmann was drafted in 1941; armed with a degree in fine arts from Harvard, he was assigned to lead the Art Looting Investigation Unit through 1946, returning to the Toledo Museum after completing his service. Among the interesting documents in this archive is a report on the Einsatzstab Rosenberg, a group responsible for confiscating Jewish-owned collections in France and a report on the collection being amassed by Hermann Göring, a senior Nazi leader and Hitler’s confidant. Dr. Wittmann was an early consultant to the Getty Museum and in 1979, he became a member of the Getty’s Board of Trustees, a position he held until 1989. The Research Institute conducted an oral history interview with Dr. Wittmann in 1995.

Craig Hugh Smyth

Art history professor and lieutenant Craig Hugh Smyth directed the activities at the Central Collecting Point in Munich, Germany, where artwork reclaimed from the Nazis was assembled after the war prior to restitution. In 1946 he returned to art history, working at the Frick Collection in New York and then at New York University. Professor Smyth’s connection to the Getty began in 1982, when he served as chair of the advisory committee for the new Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, renamed the Getty Research Institute in 1997. The Research Institute conducted an oral history interview with Professor Smyth in 1991–92.

Craig Hugh Smyth (right) at the Central Collecting Point, Munich. Photo by Johannes Felbermeyer. The Getty Research Institute, 89.P.4

Johannes Felbermeyer

Photographer Johannes Felbermeyer worked at the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut in Rome before the war, and from 1945 to 1949 he was the chief photographer at the allied Central Collecting Point in Munich. After the war he returned to his work as a photographer with the American Academy in Rome. The Research Institute’s Photo Archive holds a large collection of his photographs of ancient art as well as the photographs he produced at the Central Collecting Point.

Johannes Felbermeyer at work at the Central Collecting Point, Munich, Johannes Felbermeyer. The Getty Research Institute, 89.P.4

Following the Trail of Stolen Art

The Research Institute’s collections document various methods and means used to sell and distribute looted art. They illuminate the complex state of the art market and the various relationships between dealers, galleries, and museums during the war.

Ardelia Hall

Ardelia Hall served as a Fine Arts & Monuments adviser to the U.S. State Department after the war. The Research Institute holds a microfilm copy of the front face of over 50,000 property cards she created to document the return of stolen works of art to their countries of origin. The original cards are at the National Archives in College Park, MD. These records and more have been digitized and are available for searching online.

Dr. Erika Hanfstaengl (center) and restorer Dr. Lohe (right) at the Central Collecting Point, Munich. Photo by Johannes Felbermeyer. The Getty Research Institute, 89.P.4

The Research Institute also preserves the archives of dealers, scholars, and artists whose professional and personal lives were profoundly impacted by Hitler’s anti-art and anti-Semitic policies, such as:

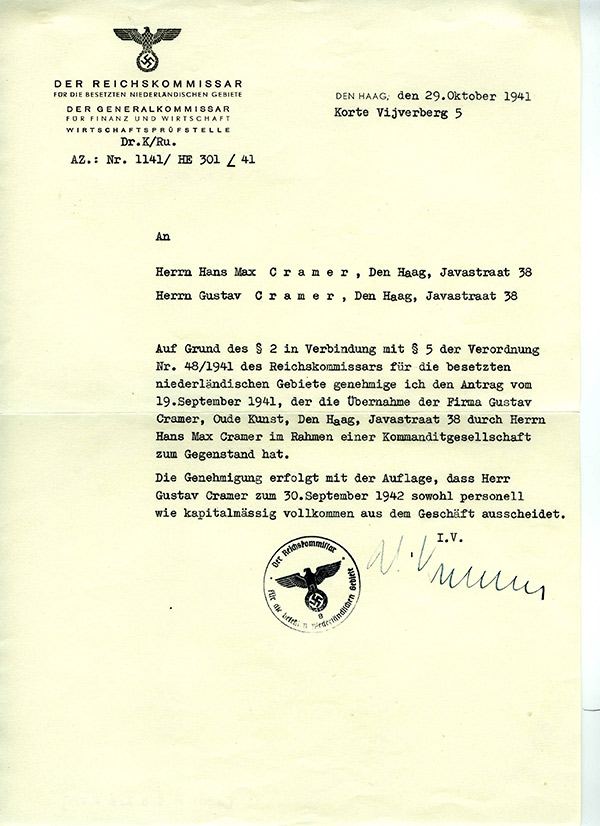

Oude Kunst Gallery

Gustav Cramer operated the Oude Kunst gallery in Berlin from 1933 to 1938, when he moved to The Hague to protect his family from Nazi persecution. After the German invasion of the Netherlands, Cramer was forced to cede legal ownership of the gallery to his son Hans. Gustav and Hans Cramer were obliged to cooperate with the Nazis, often serving as intermediaries between Nazi art agents and Dutch collectors. The uncensored documentation of the gallery’s activities under Nazi occupation during WWII, especially correspondence and receipts regarding the gallery’s dealings with Nazi agents for Adolf Hitler’s museum in Linz, is extraordinarily valuable. The gallery survived the war and continues to this day.

Letter to Cramer ordering the transfer of the gallery from Gustav to his son Hans. G. Cramer Oude Kunst gallery records 1901-1998. The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.5

Wilhelm Arntz

Wilhelm Arntz was a German lawyer and 20th-century art scholar who was involved in cases concerning the restitution of artworks confiscated by the Nazis. This comprehensive archive also documents Arntz’s interest in tracing the Nazis’ campaign against modernist art and includes numerous letters from artists who were persecuted by the government. There are also unique photographs of the 1937 degenerate art exhibition in Munich. The exhibition was recreated at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1991.

Alois Schardt

German art historian Alois Schardt was director of the National Gallery in Berlin for a few short months in 1933. As an expert on Expressionist art, which was considered “degenerate” by the Nazis, he was dismissed from his position and forbidden to speak about or publish on the subject. The Schardt archive chronicles in painful detail his increasing difficulties with the Nazi government and includes postwar letters from other Germans involved in the controversies surrounding Expressionist art, as well as letters in English covering Schardt’s problems finding employment in the Los Angeles area, where he and his family emigrated, living from 1940 to 1956.

As art librarians we provide reference assistance to these rare and highly sought-after collection materials. We are still making discoveries and learning more each time we consult these archives to facilitate the research of our library patrons. We have 50 years of combined experience working with these collections, and it is wonderful to see renewed interest in these personalities and their time as they live on both through these archives and on the silver screen.

For further information on the Monuments Men and their era, readers may also want to consult The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War by Lynn H. Nicholas, which was made into a documentary film in 2007.

I am nearly finished reading The Monuments Men and looking forward to seeing the movie tonight!

Dr. Pleasants ( Uncle Fred, Freddie, or Fred ) was a friend and more to me during the last couple of years of his life. In addition to whatever work he did as a Monuments, he was a cool guy! I was delighted to see his picture at the head of this article. Thanks.

Is this the same F. Pleasants who taught at the U of A in Tucson, AZ. My mother worked for him.

While living in Amsterdam in 1988 I was able to interview several people who had aided in the removal of the Rembrandts and Jan Steen collections from The Rjiksmuseum during the German occupation. I believe I still have my notes and photos and some audio cassette from the people I spoke with about their involvement in the preservation of Dutch Art. I would be happy to donate any and all information I have if it would be of value at this point in time, if nothing more than a personal history of some very brave and dedicated Dutch people. Let me know if this might be of interest to anyone. Most sincerely, Dannielle Robertson