What do medieval art and Jackson Pollock have in common? A lot more than you’d think

The Ascension of Christ (detail) from the Laudario of Sant’Agnese, about 1340, Pacino di Bonaguida. Tempera and gold on parchment, 17 1/2 x 12 1/2 in. (44.4 x 31.8 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 80a, verso. Photo: Nancy Turner

Mural (detail), 1943, Jackson Pollock. Oil and casein on canvas. University of Iowa Museum of Art, Gift of Peggy Guggenheim, 1959.6. Reproduced with permission from the University of Iowa.

This week features two seemingly unrelated end points: the 561st anniversary of the end of the Middle Ages (on May 29) and the close of the exhibition Jackson Pollock’s Mural (on June 1). What do the two have in common? Put simply, abstraction.

First, A Little History

The Middle Ages ended on May 29, 1453—or at least, that’s how some have chosen to write the history of a period spanning over 1,000 years. Depending on your point of view, the Middle Ages started either from the adoption of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire at the time of Constantine in the 4th century AD, or in the year 476 when the last Roman emperor was deposed. And they are thought to have ended when Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), once the capital of Byzantium, was conquered and became part of the Ottoman Empire.

At the Getty, the Middle Ages are always very much alive—not only due to our ambitious program of exhibitions drawn from the Museum’s permanent collection of manuscripts, but also because in our team of medievalists and manuscripts curators, we are always looking for ways to bring the medieval world to life in our galleries and online. In fact, two exhibitions featuring Byzantine medieval art are on view right now at the Getty Villa and the Getty Center: Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections at the Getty Villa and Heaven and Earth: Byzantine Illumination at the Cultural Crossroads at the Getty Center. These exhibitions locate Byzantine art between the ancient Greco-Roman cultures and the Early Modern, or Renaissance, world and consider the broader global context in which this vast empire thrived for centuries. These exhibitions provide a glimpse into the long Middle Ages in Byzantium, from beginning to end, and beyond.

Byzantium in Focus

The Presentation in the Temple (detail) from a Gospel Book, late 1200s, unknown illuminator. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 8 1/8 x 5 7/8 in. (20.6 x 14.9 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig II 5, fol. 129v; Initial I: Virgin and Child (detail) from the Abbey Bible, about 1250–62. Tempera and gold leaf on parchment, 10 9/16 x 7 ¾ in. (26.8 x 19.7 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 107, fol. 194v

The Byzantine city of Constantinople (today Istanbul) holds special prominence in history as being at various times the capital of the Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman empires. Several manuscripts in the Getty’s collections reveal the city’s importance during the Byzantine period; others call attention to the 1453 event, the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans, that signaled its end. The Virgin and Child in a scene of The Presentation in the Temple from a Gospel Book (above left) created around the time that Latin (read: Western European) crusaders sacked Constantinople in 1204 bears strong stylistic resemblance to the same figures in a Bible (above right) made in Bologna in the mid-1200s. This dialogue between Byzantine and Western European manuscripts is at the core of the Getty Center exhibition, a theme explored further by curator Elizabeth Morrison here.

On a related note, I’ve been studying pages from a set of choir books commissioned in the mid-15th century by Cardinal Bessarion, whose life and religious career bridged Byzantium and the West. He was at once a cardinal in the Catholic Church and the patriarch of the Orthodox Church. While in Italy, he attended a series of church councils that attempted to unite the Western and Eastern churches, and the choir books were intended as instruments of that goal of unification (Bessarion’s coat of arms appropriately features two hands grasping a cross). The books never reached their intended destination of Constantinople, since the city fell before their completion, and so they instead remained in Italy. The image of King David Lifting His Soul to God (below) from one of the choir book volumes has a decidedly abstract quality that, to our eye, looks powerfully modern.

Initial E: David Lifting up His Soul to God (detail) from the Antiphonal of Cardinal Bessarion, about 1455–60/63, Franco dei Russi. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 28 x 20 ¼ in. (20.3 x 19.1 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 99, recto

The artist Franco dei Russi provided a literal representation of the words to the hymn “To you, my God, I lift my soul,” which would have been sung over the course of the church service introduced by the page above. The ineffable, intangible, and indeed abstract “God” and “soul” are given physical presence as a bearded man with a triangular halo (referencing the Trinity, more below) and as a small, ghostlike, gray figure in David’s palm, respectively. Although the original manuscript was commissioned just after the so-called end of the Middle Ages, the artist borrowed from the medieval pictorial and theological traditions combined with an attention to anatomy, movement, and space that begins to approach our typical ideas about Renaissance art.

Abstraction, Then and Now

The presence of Jackson Pollock’s Mural at the Getty—displayed by perfect coincidence adjacent to a drawings exhibition called Hatched! Creating Form with Line—has provoked much discussion with my colleague Megan McNamee in the Manuscripts Department about the notion of abstraction in the Middle Ages. Pollock’s seemingly veiled forms and colorful, rhythmic painted lines on a modern canvas, together with the diagonal, overlapping, or contour-hatched lines that artists routinely employed in drawing from the 15th to the 19th centuries calls attention to the idea of how artists create, conceal, or eschew representational form.

The Trinity (detail) in Saint Augustine’s City of God, about 1440–50, Master of the Oxford Hours. Tempera colors, gold and silver paint, and ink on parchment, 14 ¼ x 10 ¾ in. (36.2 x 27.3 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XI 10, fol. 2

Defining Abstraction

Abstraction (from the Latin verb abstrahere, to draw away, to divert, to withdraw) is generally understood across various historical periods as the opposite of a concrete reality centered on representation and sensorial perception, or grounded by the rules of perspective and spatiality. The notion of “humanity,” for example, is an abstract idea derived from the more concrete truth that some people are “men” while others are “women,” physical individuals that can be experienced, known, and sensed individually.

Some medieval thinkers understood a distinction between perceived reality and mental images (thoughts, imagination, visions), since the latter cannot be physically made of the same material stuff as the object in the world. Thus a sword, cathedral, or dragon pictured in my mind or in art are considered abstract since they are not literally made of metal, stone, or slimy scales. Concepts central to Christianity such as the Holy Trinity can be understood in word and image because, according to the Gospel writer John, Christ (as the divine word, or logos, sent by the Father) “became flesh and made his dwelling among us.” The Holy Spirit, scripture often records, descends like a dove: thus the abstract tripartite Father-Son-Spirit are given form by way of metaphor and incarnation, as expressed in the writings of Saint Augustine (in the image above) and Boethius (see this image).

Pentecost in the Stammheim Missal, probably 1170s. Tempera colors, gold leaf, silver leaf, and ink on parchment, 11 1/8 x 7 7/16 in. (28.2 x 18.9 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 64, fol. 117v; Pentecost in the Laudario of Sant’Agnese, about 1340, Master of the Dominican Effigies. Tempera, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 16 15/16 x 12 ½ in. (43 x 31.7 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 80, verso; Pentecost, miniature from a devotional or liturgical manuscript, about 1460–70, Girolamo da Cremona. Tempera colors and gold paint on parchment, 7 15/16 x 5 1/16 in. (20.1 x 12.9 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 55, recto

Creating and Concealing Form

The progression of pictorial arts from Romanesque to Gothic to early Renaissance is at times taught as a simple move from abstraction to increased naturalism, as suggested by the three images of Pentecost shown above, in chronological order from left to right. The Apostles sit frontally, dominating a space that evokes and abstracts contemporary 12th-century architecture in the image at left. The artist even references the striped arches of Saint Michael’s Church in Hildesheim, for which the manuscript was made, while at center the figures are seated in the round within an ecclesiastical setting inspired by Gothic architecture. At right, we as viewers become part of the gathering and can almost enter into the room because of the artist’s use of perspective, and we are even given a glimpse of the world beyond the high window. Looking closely at the last image, we see that the artist represented the trees and bird beyond the window as simple dots and strokes, the very components that seem to make up the composition of Pollock’s Mural.

Abstraction is not simply the opposite of naturalistic or representational art, however. It can also be an attempt to explain, depict, allegorize, or imagine the intangible with tangible ideas. Moreover, on a material level, the very art of painting—whether in a manuscript or on a modern canvas—can be understood as the act of creating or concealing form through the combination of strokes of paint in varying colors and layers.

Around the year 1400, Cennino Cennini wrote in his treatise The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il libro dell’arte) that painting calls for imagination in order to make the unseen seen and to render the physical in a visual way by applying colored pigments in layers or juxtapositions (as in the details of paintings at the top of this post). Perhaps the best connections between medieval painting and Jackson Pollock’s Mural are the numerous iterations in manuscripts of interlace or foliate patterns, which become veils that at times conceal or reveal forms, recalling Pollock’s notion of veiled images.

Inhabited Initial C (detail) from Montecassino Breviary, 1153. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 7 9/16 x 5 3/16 in. MS. LUDWIG IX 1, FOL. 138V; Ornamented Monogram VD (detail) from Beauvais Sacramentary, about 1000 – 1025. Tempera colors, gold, silver, an ink on parchment, 9 1/8 x 7 1/16 in. MS. LUDWIG V 1, FOL. 1V; Canon Table Page (detail) from Zeyt’un Gospels, 1256, T’oros Roslin. Tempera colors, gold paint, and ink on parchment, 10 7/16 x 7 1/2 in. MS. 59, FOL. 4

The four images that follow present a sample of the ways in which we might define abstraction in the Middle Ages, but certainly many more exist in the Getty collection. Even if the Middle Ages are a distant historical memory, we can always find links and threads that draw us back to that thousand-year period that continues to have great relevance for us today.

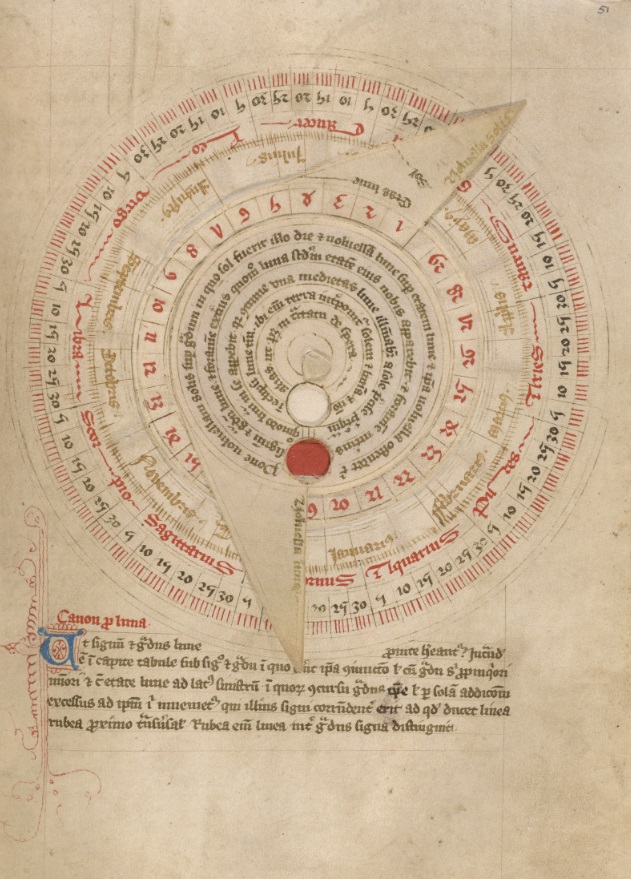

Calculating the Cosmos

Astronomical Table with Vovelle, late 14th century, shortly after 1386. Pen and black ink and tempera on parchment, 8 3/8 x 6 in. (21.3 x 15.2 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XII 7, fol. 51

Conversing with the Invisible

A Priest and Guy’s Widow Conversing with the Soul of Guy de Thurno (detail) from The Vision of the Soul of Guy Thurno, 1475, Simon Marmion. Tempera colors, gold, and ink on parchment, 14 5/16 x 10 1/8 in. (36.4 x 25.7 cm ). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms 31, fol. 7

Bounding through a Swirl of Strange Creatures

Inhabited Initial H (detail) from Gratian’s Decretals, about 1170 – 1180. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 17 7/16 x 11 7/16 in. (44.3 x 29.1 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIV 2, fol. 8v

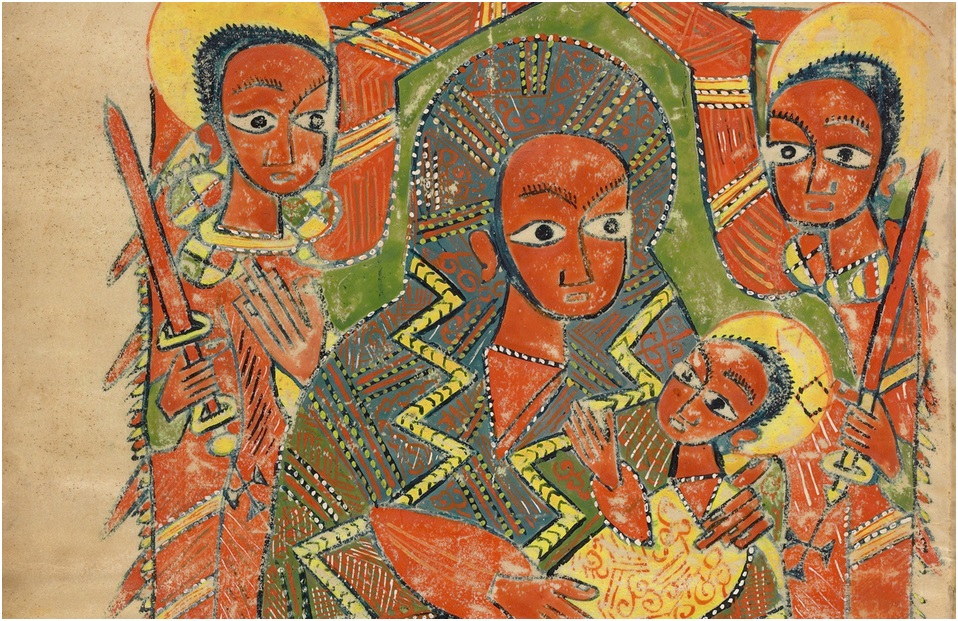

Woven Abstractions

The Virgin and Child with the Archangels Michael and Gabriel (detail) from Gospel Book, about 1504 – 1505. 13 9/16 x 10 ¼ in. (34.5 x 26.5 cm). MS. 102, FOL. 19V

Sincere thanks are due to Megan McNamee, former graduate intern in the Manuscripts Department, for her insights and the many early morning, pre-coffee conversations that helped shape this post.

Comments on this post are now closed.