The fifth season of Game of Thrones has come and gone, and like last season, we’ve recapped each week’s episode with medieval art.

To keep things interesting, we’ve added a few twists: We’ve included some wildcard images from other museum collections during our recaps, and have written featurettes about ten themes from medieval literature that dovetail with subjects covered by the popular HBO series below. Valar morghulis! All men must die!

Adonibesek’s Limbs are Cut Off; Adonibesek Laying under the Table of Simeon and Judah, about 1400–10, unknown illuminator. Tempera colors, gold, silver paint, and ink on parchment,13 3/16 x 9 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 33, fol. 124

Violence

Every period in human history has witnessed violence caused by wars, civil disputes, or acts of vengeance and retribution, but the Middle Ages are often considered to have been especially violent.

This perception is in part based on the wealth of surviving images and texts from the period that depict or describe gruesome torture, bloody battles, horrifying pestilences that attacked entire communities, brutal tournaments, and physical pain and suffering. Many of these scenes present the multifaceted nature of death, which was at the forefront of the medieval mind. One of the most violent manuscripts in the Getty collection is Rudolf von Em’s World Chronicle. It is a compendium of world history, which by default contains countless scenes of human conflict and violence (armies decimating armies, limbs and appendages being hacked off, or the earth swallowing evil clans).

For an even more in-depth look at violence in the Middle Ages, check out this extended featurette on our Tumblr.

Philosophy Presenting the Seven Liberal Arts to Boethius, about 1460–70, Coetivy Master (Henri de Vulcop?). Tempera colors, gold leaf, and gold paint on parchment, 2 3/8 x 6 11/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 42, leaf 2v. Saint Catherine Presenting a Kneeling Woman to the Virgin and Child, about 1400–10, French. Tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, and ink on parchment, 7 7/16 x 5 3/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 4, fol. 105

Women

Popular imagination often equates medieval women with damsels in distress, but most women, however, were working peasants, nurturing wives and mothers, or pious nuns, but a significant number also held prominent roles as queens, duchesses, nobles, scholars, or even artisans (and eventually, a growing middle class allowed more women to commission art and become learned readers).

The image above provides a broader range at how women may have dressed, and depicts women in positions of authority. In the image below, a woman from a noble house is presented by her patron saint, Catherine of Alexandria (who was a model of scholarship and piety). The woman was likely named Catherine and is among the numerous women who were patrons or recipients of illuminated manuscripts.

For an even more in-depth look at women in the Middle Ages, check out this extended featurette on our Tumblr.

The Lamb Defeating the Ten Kings, about 1220–35, unknown illuminator. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 11 9/16 x 9 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Ms. 77, recto

Apocalypse

Around the year 1000, many feared that the world would come to an end (based on beliefs derived from a range of interpretations of scripture). This same fear was rekindled a number of times throughout the pre-modern world, such as after the Black Death (1348) and around the year 1500.

One particular type of manuscript encapsulated how the end times would come to pass: the Apocalypse manuscript. Named for the last book in the Christian Bible (sometimes also called the Book of Revelations), these contain the visions of Saint John the Divine, who was believed to have witnessed the cataclysmic events that anticipate and befall earth’s final days, and often feature commentaries. In this example we witness a great battle between a personification of Christ and ten false kings, whose decapitated heads and bodies are devoured by a dragon-like serpent in hell (representing Satan).

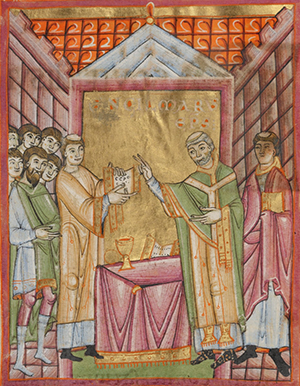

Bishop Engilmar Celebrating Mass, about 1030–40, unknown illuminator. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 9 1/8 x 6 5/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig VII 1, fol. 16

The Altar

The focal point of medieval Christian liturgy, worship, and devotion was the altar. Church architecture directed the faithful towards the High Chapel altar, where holy mysteries were commemorated through the celebration of the Eucharist, the Holy Communion of Christ’s body and blood symbolically represented through bread and wine.

The Getty Sacred Sacristy gallery (N103) brings together other special objects used on the altar during the mass, such as metalwork, a reliquary, a censer, and a basin for holy water. From the sixteenth century onward, tensions between Catholics and Protestants led to a reduction of ornament in churches built by devotees of the latter tradition.

The altar was a total olfactory space (with the sound of chant, the smell of incense, the taste of bread/wine, the sight of colored vestments and ritualistic gestures, and a range of tactile experience), and it was also a place of confession, limited access, and even rarely, of murder.

Decorated Text Page with a VD Monogram from the Stammheim Missal, probably 1170s, German. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 64, fol. 84v

The Virtue of Justice

The medieval church championed seven virtues, three theological (faith, hope, and charity) and four cardinal (prudence, fortitude, temperance, and justice). Each virtue was personified in works of art, as shown for example in this decorated text page showing temperance pouring alcohol from a flask, prudence holding a serpent, fortitude wearing armor, and justice holding a pair of scales. The last of these virtues—justice—points to the carefully balanced scale, the stability of which could be compromised with even the slightest change, as her gesture implies.

Justice was regulated differently according to a range of legal traditions: Roman, canon (or church), and feudal, among them. Illuminated manuscripts often contained beautiful illuminations that added naturalism, drama, and beauty to otherwise dry texts.

Liber Alchandrei philosophi, about 1405, Virgil Master. Tempera colors, gold paint, gold leaf, and ink on paper, 15 3/8 x 12 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Ms. 72

Memory, Knowledge, History

The shelves of public and private libraries across Europe in the Middle Ages and Renaissance were filled with books (decorated and undecorated) from a variety of genres: devotional, philosophical, scientific, mathematic, historical, literary, and so on.

The pages of this manuscript bring together the astronomical writings of the philosopher Alchandreus with texts on mathematics and music by Boethius. These author-portrait-presentation pages lend a sense of the eyewitness to the words found within the book. Other examples include Vasco da Lucena presenting the Romance of Alexander the Great to Charles the Bold; Jean Froissart giving the text of his Chronicles to Gaston Phébus; and a copy of Boccaccio’s The Fates of Illustrious Men and Women being presented to a king.

For more on manuscripts and memory, turn to the authoritative source: Mary Carruther’s The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture.

Table of Consanguinity and Table of Affinity in Gratian’s Decretals, about 1170–80. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIV 2, fols. 227v–228

Family

Manuscripts offer numerous glimpses into aspects of the medieval household, including scenes of different kinds of family units, of birth, child rearing, adolescence, marriage, and funerary rituals. Perhaps the most interesting images about kinship are the Table of Consanguinity and the Table of Affinity. These diagrams visually explain the laws that determined the number of degrees of separation that needed to exist between two individuals intending to enter into marriage, or alternatively, they represent the ways in which two individuals’ blood lines intermingled. Additionally, the tables helped determine issues of inheritance.

The Embassy of the Duke of Brabant before the King of France and the Duke of Berry in Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, Master of the Getty Froissart, about 1480—83. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIII 7, fol. 272v. A Young Knight in Armor Kneeling in Prayer before Saint Anthony in The Discovery and Translation of the Body of Saint Anthony, about 1465–70, Dreux Jean. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XI 8, fol. 50

Alliance and Allegiance

Kingdoms rose and fell in the Middle Ages as a result of forged or broken alliances and shifting allegiances. Gifts in the form of luxury objects, precious materials, exotic goods, or even manuscripts soldered unions and affirmed a commitment to defending mutual interests.

Marriage at a courtly level often served political, territorial, and economic ends; at a local level, the union of two souls in matrimony generally benefitted a patriarchal hierarchy. History manuscripts, like Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, helped medieval viewers visualize the past and prepare for the future, often through lessons learned from the fickle nature of Fortune’s ever-turning wheel (more below).

For the devout medieval believer, manuscripts for private and public use reminded individuals and groups to daily meditate on their allegiance to God, the Virgin Mary, and to saints and martyrs. A knight kneels before Saint Anthony in a manuscript dedicated to the posthumous miracles associated with the saint. Elsewhere in the manuscript, piety is rewarded with visions, healings, and raisings from the dead.

The Adoration of the Magi (detail), about 1460, unknown illuminator. Tempera colors, gold, and ink on parchment, 6 3/4 x 4 3/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Ms. Ludwig IX 12, fol. 256v

Global Journeys

Medieval Europeans turned to texts—including epic romances, world histories, travel literature, and devotional texts—to learn about distant lands, exotic goods, and foreign peoples. Many of these accounts were accompanied by stunning illuminations, which gave life to a world that was otherwise inaccessible.

Images of the kings (magi) who journeyed great distances to bring gifts to the infant Jesus gradually became representatives of the three continents known to European at the time. In this image, a golden cloak for the bearded, kneeling figure (Europe); a pointed headdress typical of the former Byzantine Emperor (Asia); and the turban of the Mamluk Sultan (Africa). The ships in the background further support the theme of a global journey.

Philosophy Consoling Boethius and Fortune Turning the Wheel (detail) from The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius, about 1460–70, Coëtivy Master (Henri de Vulcop?). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 42, fol. 1v

Rise and Fall of Fortune

According to medieval philosophy, Fortuna is a force to be reckoned with: she is inconsistent, fickle, unstable, the opposite of reason. She buffets you like a rock in the middle of the sea. As one medieval text states, “Fortune waits for you at the gallows, as you yourself tend the gallows” (Romance of the Rose).

If you look closely at the figure spinning the wheel, you’ll notice that she has two faces: one beautiful, the other dark and vile. These are the two sides of Fortune.

For those living in the Middle Ages, Fortune’s wheel represented an unending cycle of rise and fall, with little hope of achieving stability.

_________________

Season 5 Recap Episode Guide

Episode 1: The Wars to Come

Episode 2: The House of Black and White

Episode 3: High Sparrow

Episode 4: Sons of the Harpy

Episode 5: Kill the Boy

Episode 6: Unbowed, Unbent, Unbroken

Episode 7: The Gift

Episode 8: Hardhome

Episode 9: The Dance of Dragons

Episode 10: Mother’s Mercy

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks