The 19th century was a time of profound change in Germany. The Industrial Revolution roiled forward, the German states were unified into one nation, Goethe published his influential literary works, and psychoanalysis was invented. All of these events led to the upheaval of political, social, intellectual, and artistic life. The Romantic era was born and flourished.

The new exhibition Zeitgeist: Art in the Germanic World, 1800–1900 highlights the visual output of this remarkable century.

Zeitgeist features German and Austrian paintings, drawings, and prints made between 1800 and 1900, all drawn from the museum and the Getty Research Institute’s holdings as well as prominent local private collections. The exhibition also includes three works on paper that were recently acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum and are going on display for the first time. Each piece reflects the overarching philosophical and emotional essence of its time—in other words, the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the age.

A Monumental Landscape

Landscape, probably 1812, Caspar David Friedrich. Graphite on paper, 9 3/16 x 4 5/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013.37

Caspar David Friedrich is known for his dramatic paintings of imaginary landscapes, which began with innumerable studies of nature drawn in the great outdoors. Friedrich’s powerful skills of observation and meticulous rendering of fine details are evident in Landscape, a graphite drawing created in the spring of 1812. The tiny sketch with its minute marks requires magnification—provided in the exhibition by a hand lens—to be fully appreciated. Each dot and dash shapes the trees and rocks into vivid form. The reverse side of Landscape features a similarly exacting drawing, Study of Pine Trees and a Rock.

Friedrich’s Study of Pine Trees and a Rock, on the reverse side

Detail of Landscape showing Friedrich’s meticulous marks

Studies like these were the starting point for Friedrich’s visionary paintings, but they also spoke to the intellectual and aesthetic trends of the era. In the early 19th century, the growing field of geology uncovered new discoveries about the awe-inspiring natural forces that shaped the earth. The age and power of the earth and its environmental forces made our own human existence seem comparatively insignificant and feeble. This relationship between the natural world and human life became a rich subject for exploration in art.

A Transcendent Flower

Philipp Otto Runge was another of the foremost Romantic artists dedicated to expressing the transcendent, dominant quality of nature. While Friedrich’s vast landscape paintings focused on death and the human spirit, Runge took a more organic approach, meditating on cycles of life.

Poppy, about 1800–03, Philipp Otto Runge. Cut-out silhouette on white paper affixed to blue-gray paper, 9 13/16 x 3 15/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013.58

Runge’s Poppy, made about 1800 to 1803, is a cut-out silhouette of a white flower set against a blue-gray background. Early in his career, Runge created black silhouettes of face profiles, an example of which is also included in the exhibition. He considered white paper a better medium for conveying the vitality of plant life. The rounded petals, delicate stem, and jagged leaves were masterfully delineated with the use of scissors.

The poppy was a favorite flower of Runge’s, and it is featured in his other works, including Night (1805) from the famous Times of Day suite. The four prints in this series, which are part of the Getty Research Institute’s collection and on view in Zeitgeist, are among the most important artworks of German Romanticism. Dense with enigmatic meanings and mystic ideas, the suite ushered in a new form of symbolism that captivated contemporary viewers. While the solitary Poppy cutout appears infused with optimism, the opium flowers in Night symbolize death.

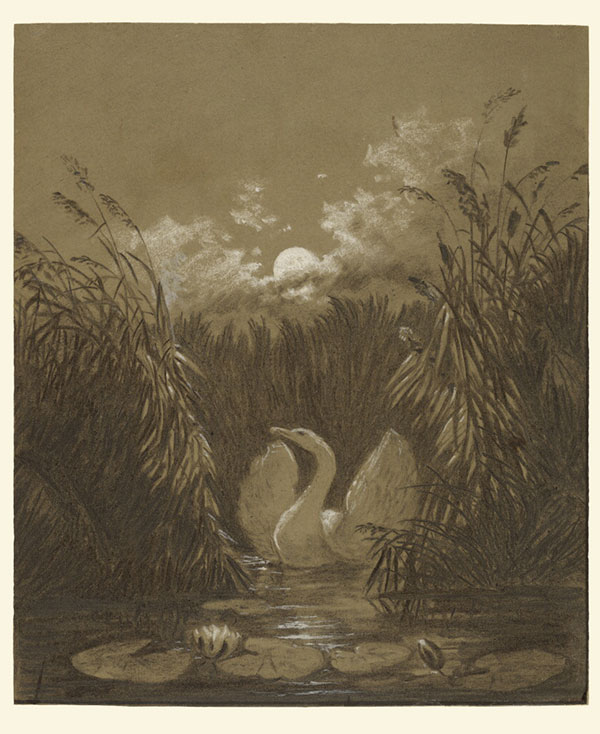

A Swan Among the Reeds

A Swan among Reeds by Moonlight, September 18, 1852, Carl Gustav Carus, charcoal with white chalk heightening on brown paper. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013.41

Artist Carl Gustav Carus was close friends with Friedrich and was strongly influenced by his nature-inspired imagery and symbolism. Moonlight is a motif frequently featured in both artists’ work. In Carus’s charcoal and white-gouache drawing, A Swan Among the Reeds, by Moonlight, a swan opens its wings, about to take flight into a moonlit night. The Museum’s Friedrich painting, A Walk at Dusk, also on display in the exhibition, features a solitary man walking beneath a bright, silver moon.

Though beautiful, the glowing moon in Carus’s drawing and Friedrich’s painting is an omen for impending death. The swan’s flight represents the soul leaving the body. For Carus, this symbolism was not purely theoretical, but grounded in real-life events. He created the drawing as a birthday gift for his daughter Clara, who was suffering from typhus. Three months later, she died.

Emblems of an Age

These artworks attest to the importance of drawing in the 19th century. Draftsmanship was an integral part of artistic training and practice, and was valued as a particularly potent form of expression. But while the forms and themes are representative of the times, these three newly acquired artworks themselves are quite rare. Runge, for example, died at the young age of 33, while Friedrich’s laborious process resulted in a limited output.

Over 100 years have passed since sweeping changes transformed the German regions; Zeitgeist revives the spirit of this era through these emblematic artworks.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.