The J. Paul Getty Museum recently announced the acquisition of a first-century carved gem that was transferred by forced sale to Adolf Hitler’s planned art museum in Linz, Austria, and later restituted to the family of its original owners. Thinking about this wartime sale, I recalled a recent discovery in the records of the G. Cramer Oude Kunst gallery at the Getty Research Institute, one that sheds light on how exactly artworks exchanged hands from dealers to Nazi officials.

Gustav Cramer (1881–1961) was a German art dealer from Berlin who specialized in Old Master paintings. In 1938, escaping the Nazi regime, he moved to the Netherlands and reopened his gallery in The Hague. With the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands in 1940, German authorities in The Hague advised Cramer to protect himself and his family from deportation by registering the gallery under the name of his son, who, according to Nazi racial laws, was not considered Jewish. The gallery was thus “aryanized” (in Nazi terminology). A similar fate struck the art dealers Alfred Flechtheim in Düsseldorf in 1933 and Georges Wildenstein in Paris in 1940, as well as many other Jewish businesses in Nazi-occupied territories.

During the war years, Cramer was exempted from wearing the yellow star in exchange for facilitating business deals with agents acting on behalf of the Nazis. He served as a purchasing agent or mediator for Julius Böhler, Erhard Göpel, Karl Haberstock, Walter Andreas Hofer, Hans W. Lange, Hans Posse, and Heinz Steinmeyer, who are all known for their involvement in art sales for Hitler and other high-ranking Nazi officials.

Wartime Invoices

In a blog post on The Iris in 2012, I wrote about some of the gallery’s wartime correspondence that exemplifies art-looting strategies in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands. At that time, the Cramer archive was not yet fully processed, and only the gallerist’s wartime letters were available for research. The gallery’s financial files were still being unpacked, so we could not yet substantiate exchanges regarding sales with invoices.

The Getty Research Institute staff continued to go through the archive, and to my surprise, near the end of the processing work—amid miscellaneous typescripts, photographs, and press clippings—I came upon a stack of approximately twenty carbon copies of invoices dating from the time of World War II.

Fifteen of these invoices document sales of paintings by the seventeenth-century Dutch painters Nicolaes Berchem, Joris van der Haagen, Paulus Moreelse, Caspar Netscher, Adrian van Ostade, Jan Pietersz Schoef, Jan Steen, David Teniers the Younger, Adriaen van de Velde, and Adriaen van de Venne, and a painting by the Italian Baroque master Domenico Fetti.

Each invoice is addressed either directly to the German art historian Erhard Göpel or indirectly to him in his role as the commissioner for the Linz museum. During the war, Göpel acted on behalf of the Reich Commissioner for the Occupied Dutch Territories and was in charge of that agency’s Special Board for Exchange of Cultural Objects. Hans Posse, the director of the Staatliche Gemäldegalerie Dresden, commissioned Göpel to explore the Dutch art market in anticipation of Hitler’s planned museum in Linz, known as the Sonderauftrag Linz. After Posse’s death in 1942, Göpel continued the work under the new director, Herman Voss, who was also in charge of the Sonderauftrag Linz.

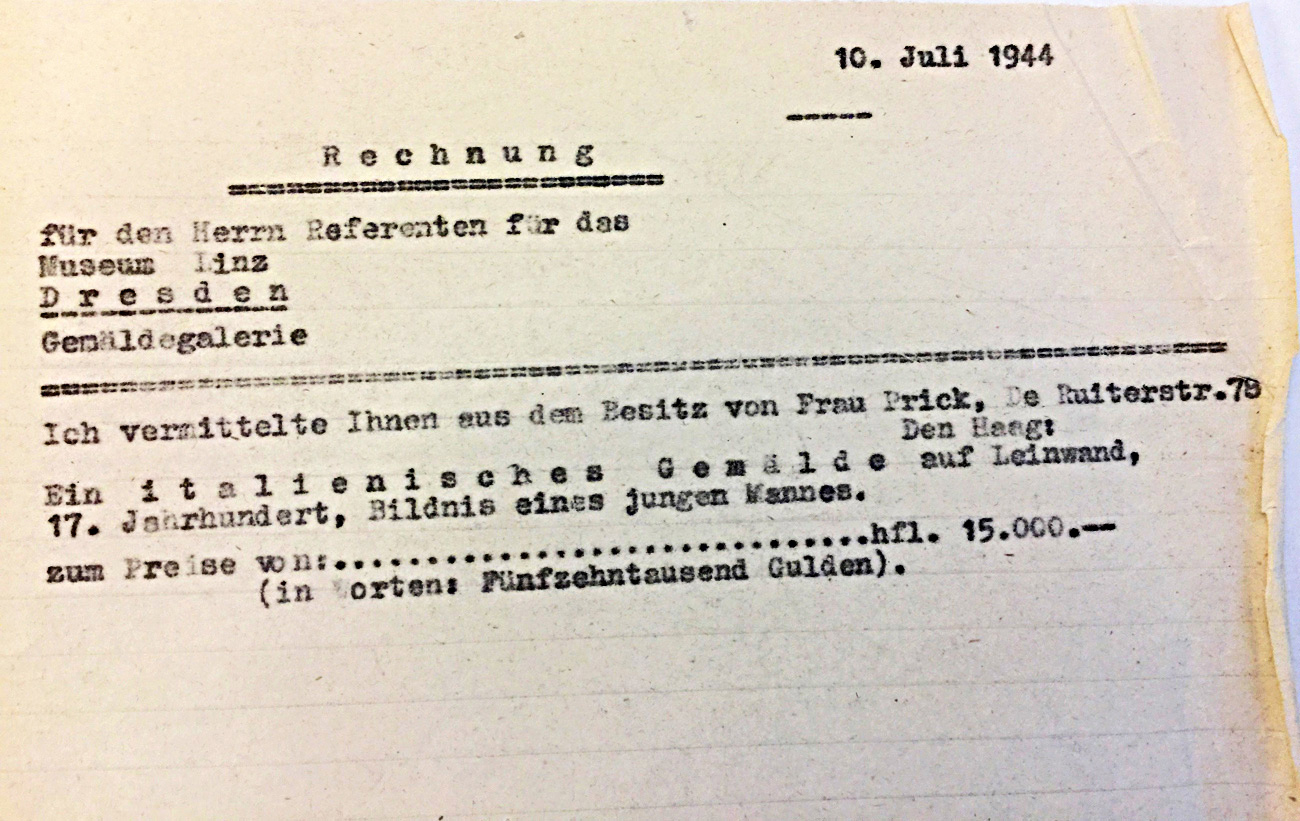

Of the invoices related to the Linz museum, only one identifies the seller of the painting. Mrs. Prick from The Hague sold Portrait of a Young Man by Domenico Fetti from her collection. The other invoices either don’t mention the seller or state that the painting in question was privately owned without disclosing the seller’s name. The absence of individual sellers’ names suggests that these were forced sales—a Nazi looting practice of forcing Jewish owners to sell desirable property far under market value.

Invoice dated March 22, 1944, addressed to the Linz museum, for a female portrait by Paulus Moreelsee, listing a reference work and the price of 25,000 Dutch gulden (guilder). It states that the painting is privately owned (“Privatbesitz”). The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.5

Matching Invoices to Inventory

All but one of the invoices in the archive are for artworks already accounted for in the inventories compiled shortly after the war by the Munich Central Collecting Point, which include records for artworks looted for the Linz museum. In 2008, the German Historical Museum, in cooperation with the Federal Office for Central Services and Unresolved Property Issues in Germany, made the inventories available to the public online.

Invoice for the sale of the Portrait of a Young Man by Domenico Fetti from the collection of Mrs. Prick in The Hague to the Linz museum on July 10, 1944, mediated by Gustav Cramer. The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.5

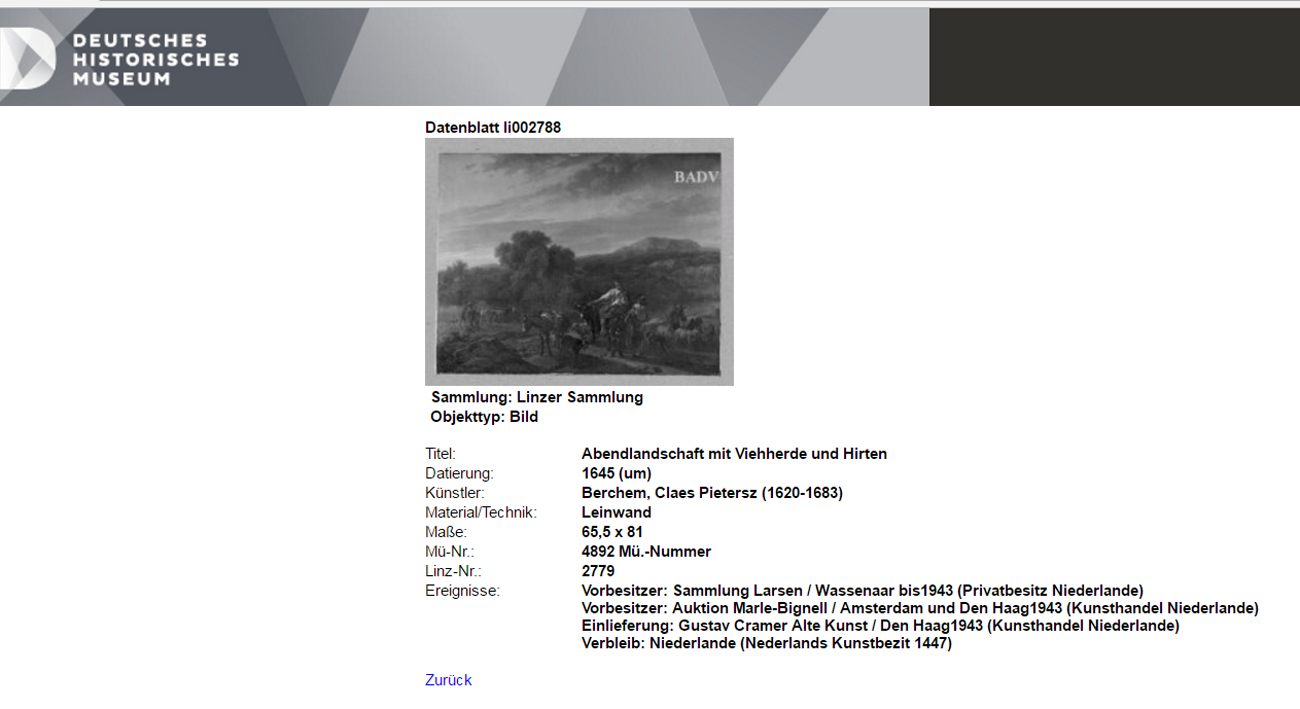

Record for Fetti’s painting in the Linz database, which confirms the painting’s provenance, the purchase price of 15,000 Dutch gulden, and Cramer’s role as a mediator.

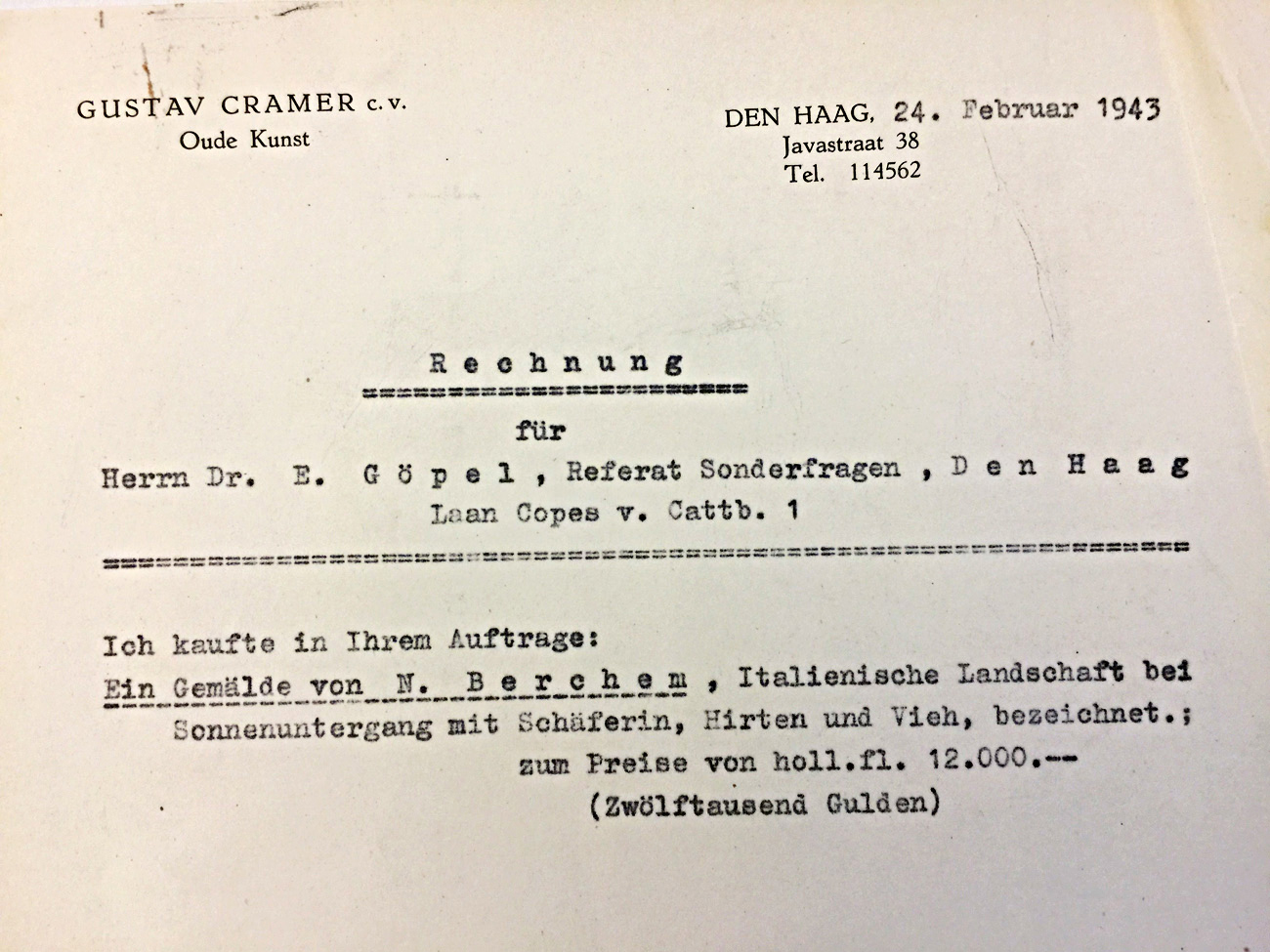

Invoice dated February 24, 1943, addressed to Erhard Göpel, for the purchase of a landscape painting by Claes Pietersz Berchem for 12,000 Dutch gulden. The painting was purchased by Cramer on behalf of Göpel. The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.5

Record for Berchem’s painting in the Linz database, which confirms Cramer’s role as the purchasing agent. The invoice provides further information about the sales price.

A provenance search for Cramer in the Linz database retrieves eighteen records for paintings delivered by the gallerist to the Sonderauftrag Linz. The invoices at the Getty Research Institute confirm that the paintings were indeed sold on the wartime Dutch art market. Occasionally, they also provide new information that is not always listed in the database, such as sales prices.

Furthermore, the invoices specify Cramer’s role as that of a mediator or purchasing agent, whereas in the Linz database his function is uniformly defined as Einlieferung, a term that suggests merely delivery. In this respect, the invoices provide more nuanced information about Cramer’s involvement with the Nazis and shed light on the various strategies the German government used when engaging third parties to facilitate business deals.

Hidden Insights

In an interview recorded at the Getty Center in 2004, Gustav Cramer’s son, Hans Max Cramer, stated that the undisclosed sellers were not always paid, and the invoices his father signed served merely as a disguise for forced sales. The Linz invoices in the Cramer archive are therefore evidence of Nazi art looting and have historical significance.

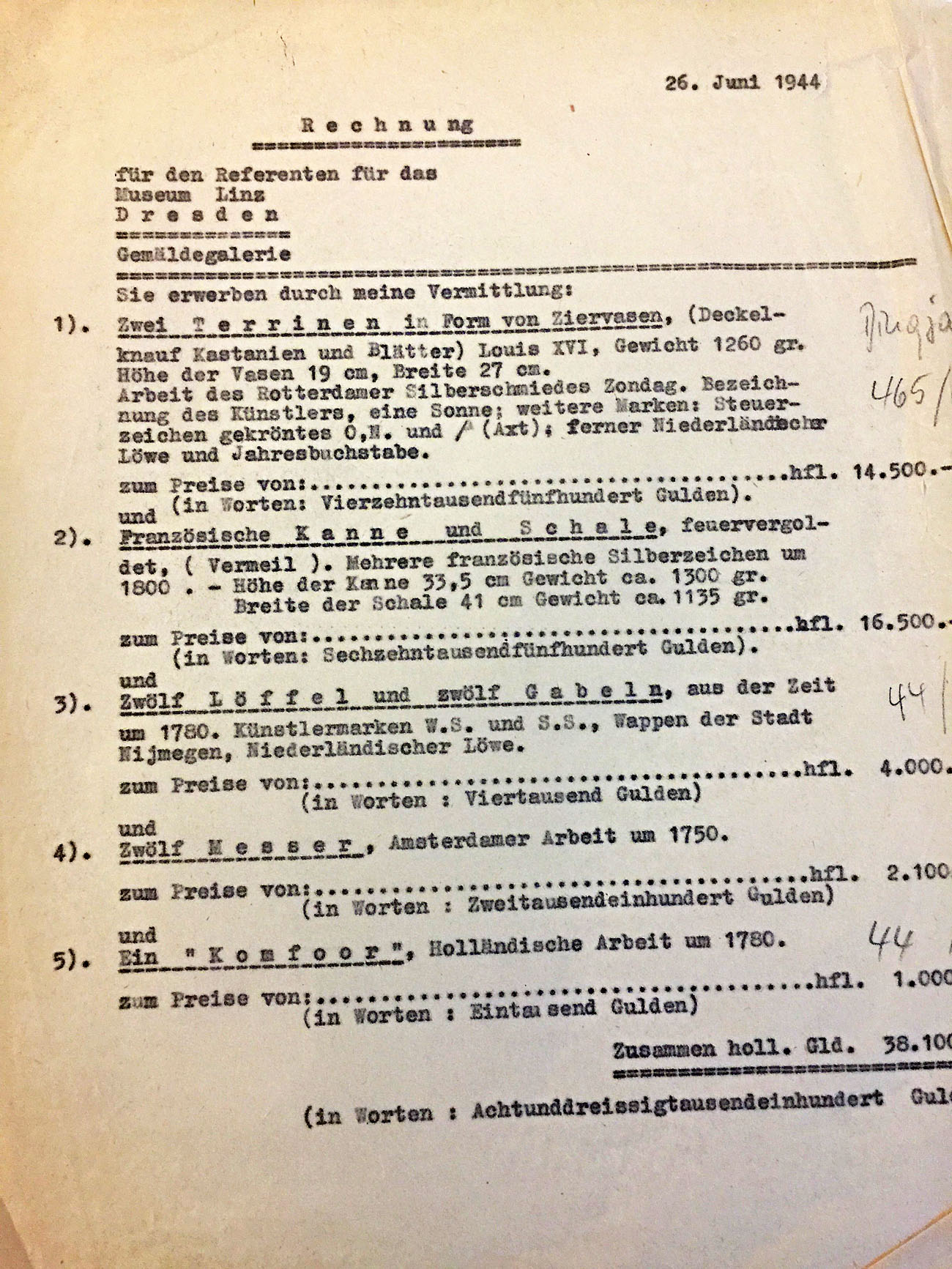

One of the wartime invoices is for the sale of five eighteenth-century French and Dutch silver objects to the Linz museum. Cramer mediated the sale on June 16, 1944. These silver objects are not indexed under Cramer in the Linz database and seem not to be accounted for in the database overall. Besides prices, the invoice provides detailed descriptions of the objects. This document may turn out to be an important lead needed to establish the identity and provenance of these objects, as well as their current location.

Invoice for the sale of five 18th-century French and Dutch silversmith art objects to the Linz museum on June 26, 1944, mediated by Gustav Cramer. This purchase is not indexed under Cramer in the Linz database. The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.5

The archive also includes Gustav Cramer’s exchanges with the Nazi government in The Hague, official documents, and personal letters to friends and relatives describing the Cramer family’s distressing experiences with Nazi racial policy and the daily hardships of survival under occupation in the Netherlands.

The wartime records of the G. Cramer Oude Kunst gallery at the Getty Research Institute offer an illuminating, uncensored window into the art market in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands. This valuable resource is now fully processed and open to researchers ready to uncover more hidden information.

See all posts in this series »

Very informative article! I believe I spotted an error, though: Linz is not in Germany but in Austria.

Hi Saskia, Thank you so much for pointing out this error, the post has been fixed. While the Sonderaufrag Linz was established in Germany (Dresden), the museum itself was planned for Linz, Austria. —Annelisa / Iris editor