In 1917 Ernst Ludwig Kirchner expressed his hopes and fears about World War I through a series of fascinating watercolors of the Apocalypse, rendered at tiny size on the back of cigarette packages

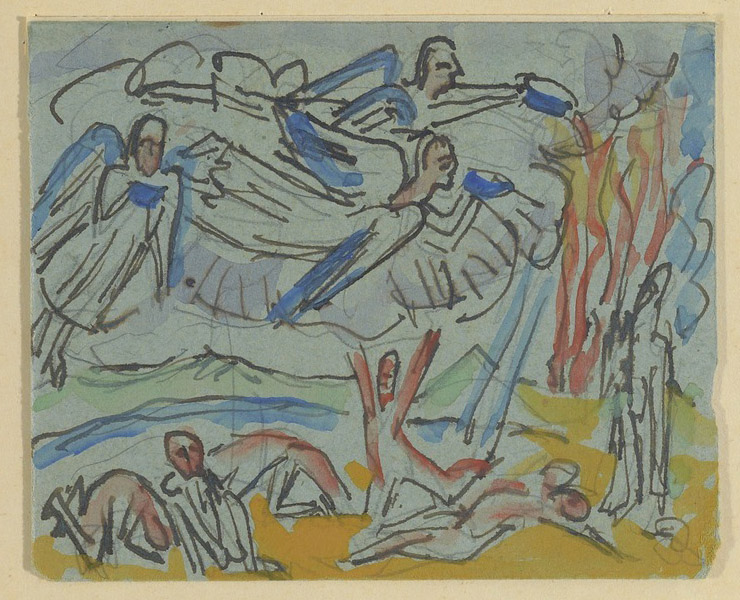

Saint John’s Vision of the Seven Candlesticks, 1917, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Sketchbooks, 1917–1932. The Getty Research Institute, 87-A487

One hundred years ago, on August 1, 1914, Germany declared war on Russia—the second in a series of fast-issued war declarations that followed the June 28 assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Serbian nationalists in Sarajevo. This ultimately led to the First World War, one of the deadliest conflicts in history. With its introduction of modern warfare on a broad scale, this war became known as the veritable Apocalypse, one that would change Europe forever.

The story of Revelation, as the Apocalypse is described in the bible, became a popular topic in European art. Many artists, including Otto Dix and Max Beckmann, addressed the theme of the apocalypse in a metaphorical way. German artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, however, approached the theme in a literal way. Kirchner’s miniature drawings of the Revelation from 1917 mirror not only his own hopes and fears, but that of an entire generation of modern artists at the beginning of the 20th century.

The years leading up to the war were marked by industrial and technological innovations in Europe, which triggered increasing discontent with traditional social and political structures. Intellectuals, especially, perceived conventional forms as hindering creativity and individual growth. Thus, many met the prospect of war not with horror, but with hope for a transformation of society and the arts. Artists longed for a liberating and cathartic experience and new inspiration for their work. Soon, of course, they would encounter a reality that was far from their idealized visions.

Hope and Disillusionment

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner did not long to participate in actual combat. Instead, he placed his hopes in the possibility that the war would provide a change in people’s appreciation of art. In a letter to his friend Gustav Schiefler in 1915, Kirchner wrote: “I also believe that many of those who stood on the battleground discovered humanity and thus are able to appreciate the expression of human feeling in art. The development of these men and of creators is parallel because both set aside their ego in order to fulfill this noble task.” These hopes did not come true and Kirchner soon realized that “the war is catching on more and more. One only sees masks, no more faces.”

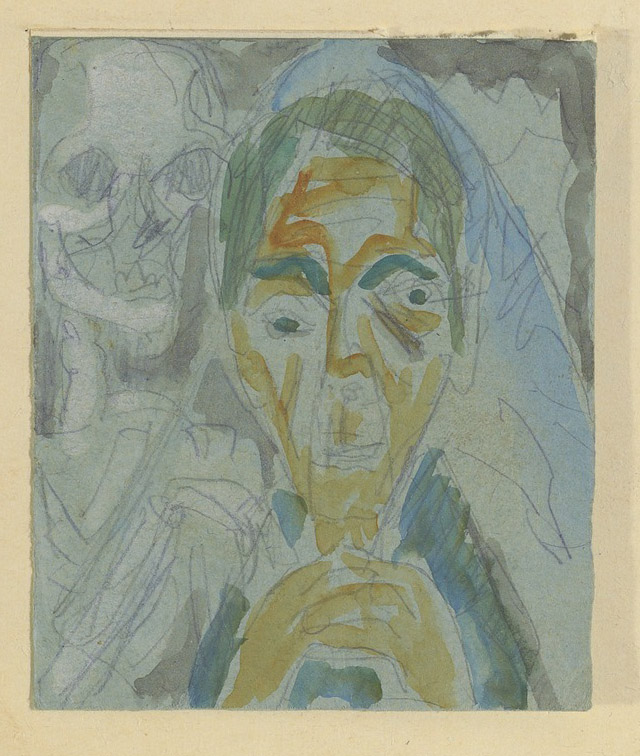

In 1917, he created 11 drawings of the Apocalypse on the back of cigarette boxes and a Self-Portrait with Death, which precedes the series and reveals it to be deeply personal. These tiny watercolors—each only 2 ½ inches high—were bound into an album that is now held in the Special Collections of the Getty Research Institute. (See the fully digitized album here.)

Self-Portrait with Death, 1917, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Sketchbooks, 1917–1932. The Getty Research Institute, 87-A487

Kirchner most likely conceived these miniature works of art during one of his stays at a sanatorium in Switzerland, where he tried to recover from severe physical and mental illness, which had been intensified by his fear of the war. From the biblical story, Kirchner selected key events such as the Twenty-four Elders before the Throne and the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. However, his selection is a highly personalized one, which is illustrated mainly by his omission of the ultimately positive ending of the Apocalypse: the creation of a New Jerusalem. Instead, his focus remains with the plagues humankind must endure, such as Angels Pouring Out the Vials with God’s Wrath.

Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, 1917, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Sketchbooks, 1917–1932. The Getty Research Institute, 87-A487

Angels Pouring Out the Vials with God’s Wrath, 1917, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Sketchbooks, 1917–1932. The Getty Research Institute, 87-A487

In an article in the Getty Research Journal, Thomas Gaehtgens and I explored Kirchner’s selections and compared his renderings to the famous Apocalypse by Albrecht Dürer. As Kirchner’s treatment of the Apocalypse has still been little studied, the album is also the focus of an ongoing collaborative digital research project, Digital Kirchner.

Kirchner was scarred by the war, which he ultimately tried to escape by moving into a cabin high up in the Swiss mountains. His fear of being drafted remained with him, however, and was painfully revived when signs of another war appeared in the 1930s. Shortly before Kirchner took his own life in 1938, he returned to the topic of the Apocalypse with plans to embellish a small chapel in Davos with scenes from the Revelation. These plans, unfortunately, were never carried out.

It is interesting to note that Kirchner, who typically focused on depictions of his immediate surroundings in his art, turned to a religious topic during the war. But the story of the Apocalypse mirrors both the hopes that Kirchner and many others had for the war, as well as the fear and disillusionment into which these were turned by the reality of the war bloodshed.

The album of Kirchner’s Apocalypse drawings will be on view in World War I: War of Images, Images of War in the Getty Research Institute Galleries, November 18, 2014–April 19, 2015.

Comments on this post are now closed.