Recipe for distilling peony water. Hand-colored woodcut from Walther Hermann Ryff’s Das new groß Distiller Buch (Frankfurt: Heirs of Christian Egenolff, 1556). The Getty Research Institute

If Whole Foods workers had read a copy of Walther Hermann Ryff’s Das new groß Distillier Buch, they might have avoided the public outcry over their expensive “asparagus water.” The key to making flavored waters is the art of distillation, a technique invented by ancient alchemists for extracting the essence of a substance through evaporation and condensation.

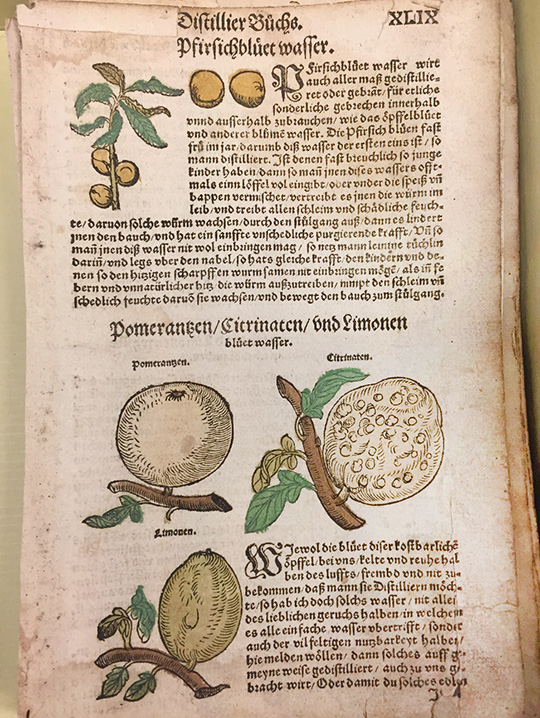

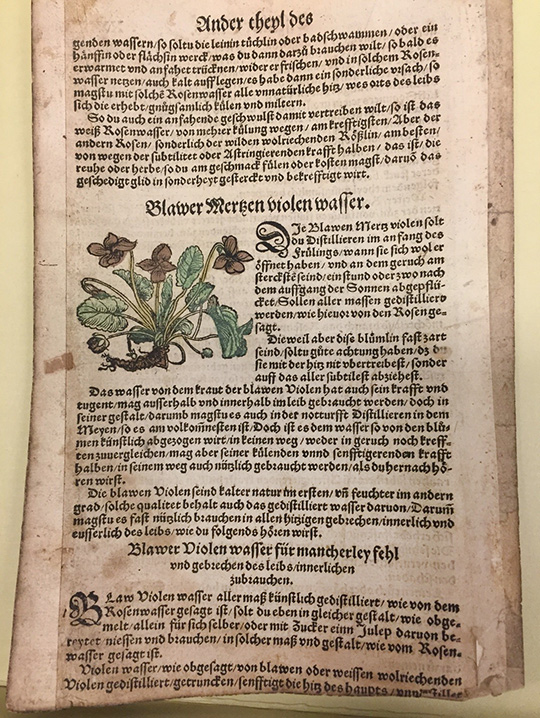

Hand-colored leaves from the second edition of Ryff’s distillation manual, donated by botanical art collector and Getty Research Institute Council member Tania Norris, contain recipes for making distilled floral and herbal waters from botanicals like violets, peonies, water lilies, and citrus. The flowers and herbs are heated in water, vaporizing certain compounds and leaving behind others, producing a concentrate of pigments, flavonoids, and aromatics—that is, the essence of the flower.

The first published book devoted solely to distillation was Hieronymus Brunschwygk’s Liber de arte distillandi de Compositis (1512). Ryff’s work claims to be a re-release of thise more famous earlier treatise, but the nature of this claim is unclear: Ryff, in addition to being a physician, was also Germany’s most prolific “writer” of scientific and technical texts over the period of a decade—frequently using pirated woodcuts and attaching his name to translations of and elaborations on work written by others.

In the case of Das new groß Distiller Buch, while Ryff repeats many of Brunschwygk’s woodcuts of distillation apparatus, he also adds a wealth of new botanical information and illustration. And, indeed, this was often the way that recipes traveled through medieval and Renaissance Europe: copied and recopied in books of secrets, printed and reprinted under new names, with pages torn out for use in the kitchen or the laboratory.

Recipes for distilling peach, bitter orange, citron, and lemon flower waters. Hand-colored woodcuts from Walther Hermann Ryff’s Das new groß Distiller Buch (Frankfurt: Heirs of Christian Egenolff, 1556). The Getty Research Institute

Ryff’s manual was primarily concerned with the medicinal uses of floral waters, but these products of distillation had a broad range of applications from the culinary to the cosmetic. While distillate of violets was prescribed for ailments like epilepsy and insomnia, it could also be used as perfume, food coloring, or delicate flavoring for food and drink. During the reign of Charles II, a favorite dessert was “violet-plate,” a kind of floral conserve made with violet extract. Orange flower water is a traditional ingredient in Spanish king cake as well as in French madeleine cookies, while rose water has been used for centuries as a perfume, skin treatment, and flavoring for marzipan and Turkish delight.

Properly made, floral waters are a feast for all the senses: giving edibles bright colors, sweet smells, and delicious flavors—with the added bonus of medicinal qualities. Whole Foods’ asparagus water was trying to cash in on just these benefits: delicious and good for you (and for a luxurious price); this is a case, however, where the trend for natural, unprocessed foods doesn’t apply. Here, a chemist (which is really just another name for cook) is needed to unlock the flavors of nature.

Recipe for distilling violet water. Hand-colored woodcut from Walther Hermann Ryff’s Das new groß Distiller Buch (Frankfurt: Heirs of Christian Egenolff, 1556). The Getty Research Institute

Loved it. Thank you.