Enfilade in the Getty Center’s South Pavilion galleries

The art of manuscript illumination is often associated with the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, but the practice of producing hand-written and embellished books continued even after the invention of the printing press. In fact, craftsmen and guilds sustained the tradition well into the seventeenth century.

Four illuminated manuscript leaves celebrating the triumphs and virtues of King Louis XIV are on view at the Getty Center as part of a campus-wide commemoration of the 300th anniversary of the monarch’s death. Adorned with gold leaf and brilliant colors, these pristine leaves of parchment were once part of a book depicting the symbols of the king.

Two of the leaves are included in the exhibition A Kingdom of Images: French Prints in the Age of Louis XIV, 1660–1715 at the Getty Research Institute, while the other two have a home at the Getty Museum’s South Pavilion in the installation Louis XIV at the Getty. Here they hang amid tapestries, cabinets, clocks, porcelain vases, and a range of other decorative objects created during Louis’s illustrious reign.

Two of the leaves are included in the exhibition A Kingdom of Images: French Prints in the Age of Louis XIV, 1660–1715 at the Getty Research Institute, while the other two have a home at the Getty Museum’s South Pavilion in the installation Louis XIV at the Getty. Here they hang amid tapestries, cabinets, clocks, porcelain vases, and a range of other decorative objects created during Louis’s illustrious reign.

At first glance, manuscripts and decorative arts may not seem to have much in common—but a closer look reveals their intertwined history.

Manuscripts featured in the Getty Research Institute galleries

Devices for the Tapestries of the King

Emblems—symbolic images usually combined with a motto or set of verses—have a long tradition in manuscripts and were particularly important in the cultural life of seventeenth-century France. Also in favor were personal devices, a simplified emblem that represents the heraldry of an exalted person or family. At the time, the display of emblems and devices was an essential component of royal processions and entries into cities. Emblems also circulated among elite members of the Académie française, the council that made rulings on all matters pertaining to the French language.

Emblems and devices were so important, in fact, that in 1663 Louis XIV’s superintendent of buildings (and later minister of finance), Jean-Baptiste Colbert, founded the Académie des devises et inscriptions, the Academy of Devices and Inscriptions. The primary goal of Colbert’s academy was to design emblems that would be incorporated into the borders of tapestries, some of the most expensive and lavish artworks of the day. The academy created a series of official emblems known as Devises pour les tapisseries du Roy (Devices for the Tapestries of the King), of which the Getty’s manuscript leaves were a part.

This book was adorned by the royal painter-illuminator Jacques Bailly, who also fulfilled several commissions for luxuriously decorated albums containing emblems for the king, his family, and members of the court.

Escutcheon with a Medal (detail) from Emblems for Louis XIV, about 1663–68, illuminations by Jacques Bailly, text in French and Latin by Charles Perrault. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 11, leaf 2

The Getty owns twelve stunning pages from this manuscript, all illuminated by Bailly. Other pages can be found at the British Library in London, the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, the Morgan Library in New York, the Houghton Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the Musée Condé in Chantilly, and private collections.

Bailly’s devices draw on poetic French texts by noteworthy members of the Académie française, such as Charles Perrault, and other contemporary authors, such as abbé Amable de Bourseis. The calligraphy was likely penned by the celebrated scribe Nicolas Jarry. The writers wove eloquent verses to explain famed Latin mottoes or extol Louis’s virtuous exploits. Bailly visualized the meaning of the phrases through allegories, landscapes, and still lifes.

The image just above depicts a medallion with thirteen spears assembled around the French royal scepter, identified by its golden fleur-de-lis. This allegory represents the alliance between France and the thirteen Swiss states, or cantons. The Latin words Custodes custodiet ipsos mean “guardians keep watch.” The manuscript’s French prose explains that the king, whose throne is unshakable, gives his protection to the Swiss such that no power will dare to offend them.

A framed manuscript leaf (on wall) in Gallery S102

Connections across Media

The royal scepter of France in this illumination can also be found on a handful of objects in the decorative arts galleries at the Getty, including the famous portrait of Louis XIV after court painter Hyacinthe Rigaud.

Portrait of Louis XIV, early 1700s, after Hyacinthe Rigaud. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 70.PA.1 (found in Gallery S101); Tapestry with the Portière aux Armes de France, woven under the direction of Etienne-Claude Le Blond and Pierre-Josse Perrot at the Gobelins Manufactory, designed 1727, woven about 1730–40. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.DD.100 (found in Gallery S109)

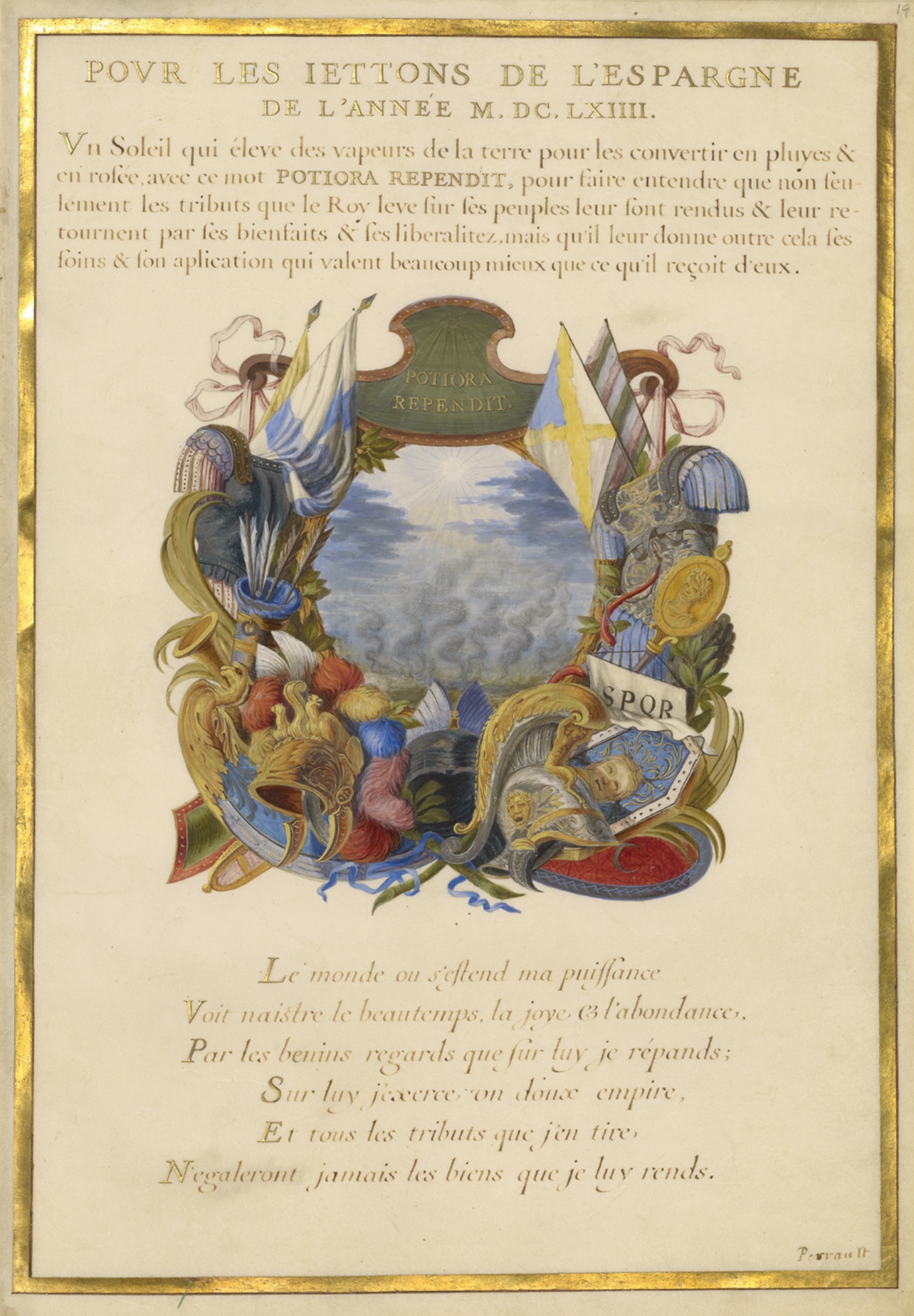

Another leaf from Devices for the Tapestries of the King contains an allegory of French dominance over Spain and the Spanish Netherlands. It resembles a similar grouping of helmets, shields, banners, standards, quivers, and the like on an impressive cabinet attributed to the greatest court furniture maker to Louis XIV, André-Charles Boulle. The imposing monumental cabinet also communicates French dominance, embodied by a carefully designed marquetry (wood mosaic) cockerel. A traditional symbol of France, this feisty rooster stands triumphant over the Spanish lion and the eagle of the Holy Roman Empire.

Escutcheon with a Landscape from Emblems for Louis XIV (text in French and Latin by Charles Perrault), Jacques Bailly, about 1663-1668. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 11, leaf 9

Another page from the set (not currently in the galleries, but viewable online) features a powerful, reclining figure of the mythical hero Herakles, who also appears holding up the right side of the cabinet. In the manuscript, Herakles rests his head on the skin of the Nemean Lion, which he vanquished as one of his twelve labors. The figure on the cabinet dons this skin as a mantle, an allusion to its protective power of invincibility. The lion was also a symbol of strength and majesty in the Baroque.

The escutcheon (ornamented shield) on the parchment page and the design of the wooden cabinet are both architectural. On the cabinet, the medallion with the lions is even set within a temple-like space atop a porphyry vase. Louis XIV drew on the symbols of antiquity in his design of the palace of Versailles, and even fashioned himself as a new Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar.

Cabinet on Stand, attributed to André-Charles Boulle, about 1675-1680. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 77.DA.1 (gallery 103); Escutcheon with a Lion Attacking a Cheetah (detail) from Emblems for Louis XIV, text in French and Latin by Charles Perrault, illuminations by Jacques Bailly, about 1663–68. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 11, leaf 4

One final page from Devices for the Tapestries of the King features a wealth of motifs found on numerous objects in the South Pavilion galleries, especially on objects displayed near the cabinet shown above.

Escutcheon with a Landscape (detail) from Emblems for Louis XIV, text in French and Latin by Charles Perrault, illuminations by Jacques Bailly, about 1663–68. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 11, leaf 5

This particular escutcheon features numerous royal symbols, the majority of which were also included in the portrait of Louis XIV: the fleur-de-lis scepter, the crown, the so-called main de la justice (hand of justice) scepter, the fleurdelisé and ermine cloak, and the badge of the Order of the Holy Spirit, an eight-pointed cross with a dove at the center. The radiant sun is a beautiful reference to the Roi-Soleil (the Sun King), as Louis fashioned himself.

Bailly painted a masterful cockerel, symbol of France, atop an escutcheon enclosing a landscape. Another example of this regal fowl can be spotted flanking either side of a clock on loan to the Getty and displayed near the Boulle cabinet.

South Pavilion Gallery 103: Wall Clock, about 1715–72, case attributed to André-Charles Boulle after design by Gilles-Marie Oppenord, and movements by Jacques Thuret. Anonymous loan

In the illumination, just beneath the rooster, we also see two dolphins. These represent the dauphin, the heir apparent to the French throne (the word dauphin literally means “dolphin”). Two coffers on stands–also attributed to André-Charles Boulle–flank the Boulle cabinet and feature dolphins whose tail flukes frame key holes. These majestic objects were possibly owned by Louis’s oldest son, also named Louis.

Detail from Two Coffers on Stands, attributed to André-Charles Boulle, about 1684-1689. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 82.DA.109.1-2

These are just a few of the connections between images in Bailly’s miniatures and objects in the Getty’s collection of French decorative arts, which we invite you to explore in the galleries as well as online.

“The calligraphy was likely penned by the celebrated scribe Nicolas Jarry.” –

Jarry was also the scribe of La Fontaine’s poem ‘Adonis’