Belvedere Antinous, about 1630, attributed to Pietro Tacca. Bronze, 25 1/2 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014.40

On the occasion of the tercentenary of Louis XIV’s death, a sculpture from his collection has entered a new chapter in its storied history. Last year the J. Paul Getty Museum acquired a bronze sculpture that once belonged to the Sun King himself, and the Belvedere Antinous, attributed to Pietro Tacca, is now on display in the South Pavilion as part of the gallery installation Louis XIV at the Getty.

The Sun King’s Sculpture

Belvedere Antinous, detail of the back of the right ankle

How do we know this sculpture once belonged to Louis XIV? The back of the right ankle is inscribed “N. 4,” an inventory number from the French royal collection. In 1711, Moïse-Augustin Fontanieu, the keeper of the royal garde-meuble or furniture repository, started numbering the objects in the collection in order to keep track of them.

Museum registrars do the same thing today. Belvedere Antinous was assigned the accession number 2014.40 when it entered the collection of J. Paul Getty Museum—though needless to say, we marked it in a far more discrete way than the large “N. 4” from the time of the Sun King. Sculptures adorned with Louis XIV’s inventory numbers can be found in other collections as well, including a Pluto figure at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Antinous or Hermes?

Belvedere Antinous, now identified as Hermes, early 2nd century, Roman. Marble, 1.95 m high. Museo Pio-Clementino, Belvedere Courtyard, Vatican, Rome

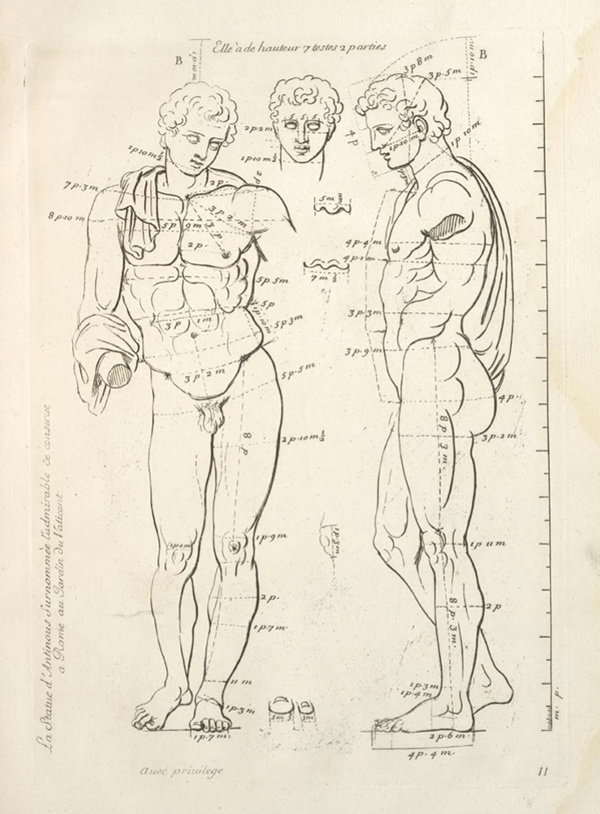

The bronze is a copy of an ancient Roman marble statue known as the Belvedere Antinous. This life-size marble was acquired by Pope Paul III in 1543 and installed in the Belvedere Courtyard in the Vatican. Many artists and collectors considered the Belvedere Antinous to be one of the most beautiful surviving statues from antiquity, and engravings of the statue were used as models in the study of perfect body proportions.

During the Renaissance, sculpted figures of alluring young males were often thought to represent the Greek youth Antinous. He is remembered as the beloved favorite of the Roman Emperor Hadrian and was renowned for his beauty. At the start of the 19th century, the antiquarian and papal keeper of antiquities, Ennio Quirino Visconti, made a strong case that the Belvedere Antinous is in fact a representation of the Olympian god Hermes, renamed Mercury by the Romans. Visconti’s theory is accepted to this day.

In Greek mythology, Hermes is a divine messenger, the god of travelers, the intercessor between mortals and gods, and the conductor of the soul into the afterlife. The Belvedere Antinous is considered a Hermes figure in the tradition of the Andros type, which is based on a marble Hermes located in the Archaeological Museum of Andros, Greece. These sculptures share a similar body position and include a chlamys—a type of cloak—draped over the shoulders, a tree trunk, and serpent.

Measuring the perfection of the Belvedere Antinous. Plate 11 in Gérard Audran, Les proportions du corps humain: mesurées sur les plus belles figures de l’antiquité (Proportions of the human body, measured from the most beautiful sculptures of antiquity), 1683. The Getty Research Institute, 84-B31091. Available digitally on the Internet Archive

Pietro Tacca’s Bronzes

Equestrian Statue of Philip IV of Spain, 1634–40, Pietro Tacca. Bronze. Plaza de Oriente, Madrid

An artist at the service of the Medici grand dukes, Pietro Tacca was one of the most important sculptors in early 17th-century Italy. After inheriting the studio of his master, Giambologna, Tacca played a critical role in maintaining Florence’s preeminence as the center for bronze casting in Europe. His equestrian statue of Philip IV of Spain in Madrid was the first large-scale monument of a horse in a rearing posture to be successfully cast in bronze. Tacca’s son, Ferdinando Tacca, also became a sculptor. The Getty Museum owns two of Ferdinando’s superb bronzes: Putto Holding Shield to His Left and Putto Holding Shield to His Right.

Inventories and payment records indicate that Tacca created several medium-size bronze sculptures for the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinand II de Medici. Among them was a now-lost Belvedere Antinous.

A Princely Tradition

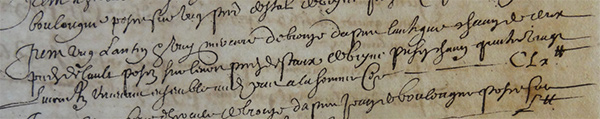

Entry related to the Getty’s Belvedere Antinous in an inventory created after the death of Louis Hesselin, 1661. Archives nationales de France

The Getty’s Belvedere Antinous was first owned by Louis Hesselin, a French aristocrat. Hesselin was active in the service of two kings. As conseiller du roi et maître ordinaire de la chambre he was responsible for paying the artists and artisans who worked for King Louis XIII. Under Louis XIV, he was intendant des plaisirs du roi, the organizer of lavish festivities. Hesselin often choreographed ballets in which he himself danced, sometimes alongside the young Louis XIV.

As a collector, Hesselin had a predilection for Italian bronzes and replicas of ancient sculptures. He traveled to Italy twice, in 1632–33 and 1637, staying in Florence, Venice, and Rome. During one of these trips Hesselin likely saw the Medici collection of bronzes and commissioned or acquired the Belvedere Antinous.

The Belvedere Antinous was one of 33 sculptures purchased by Louis XIV from the heirs of Hesselin in 1663. Starting in the Renaissance, bronze replicas of famous ancient statues were displayed in princely and aristocratic collections. The Sun King followed this noble tradition, although such objects did not align with his personal taste, which was more inclined toward hard-stone vases and gems. Louis XIV’s decision to form a collection of bronzes is characteristic of his ambitious cultural program and quest for prestige. The history of this particular sculpture—from Florence to Paris to Los Angeles—is certainly one fit for a king.

Tacca’s bronze in the new installation Louis XIV at the Getty

Comments on this post are now closed.