Bible, about 1280–90, Bologna, Italy. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig I 11, fol. 248v; National Coming Out Day (NCOD) Logo created and donated by Keith Haring to the Human Rights Campaign.

This post acknowledges and discusses important—but often overlooked—aspects of premodern life, relationships, and identities that existed beyond the gender binary (female and male) or heteronormative couplings (a man and a woman). As curators of and specialists in medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts (books made and painted by hand), our focus will be objects from the Getty collection that were produced in premodern Europe from about 1200 to 1600; we will consider the ways in which images and texts were translated, transmitted, and transformed in later centuries all the way to the present day.

Nothing Is “Normal”

Male Martyrs and Saints Worshiping the Lamb of God; Female Martyrs and Saints Worshiping the Lamb of God in the Spinola Hours, about 1510–20, Master of the James IV of Scotland. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 18, fols. 39v–40

Human sexuality and gender identity are complex topics, and our understanding of each is continually expanding and deepening. It is sometimes tempting to generalize about what constituted “normal” male and female behaviors, expectations, identities, and relationships in the past, but the norm in one place and time was not necessarily the norm in another. Even categories like male/female, gay/straight, or Christian/non-Christian risk essentializing, oversimplifying, or anachronism. Such binaries begin to break down under greater scrutiny. In scholarship, the term “queer” is often used to describe any expression of sexuality or gender that disrupts or disturbs traditional binaries. Each image discussed in this post could be described as providing a queer lens with which to view the past—“queering,” if you will. This approach is not exclusively about gay, lesbian, transgender, or straight individuals but about the potential for multifaceted, iterative, and complex identity dynamics. Before examining the fluidity of ideas like gender and sexuality in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, it is important to acknowledge that many of the terms we use today (and continue to develop and refine) such as hetero-, homo-, bi-, and a-sexual, did not exist at the time. Rather than attempting to redefine or label these works, we hope that by approaching the material with a new critical vocabulary we may uncover a narrative that was rarely depicted, difficult to see, and often too easily ignored.

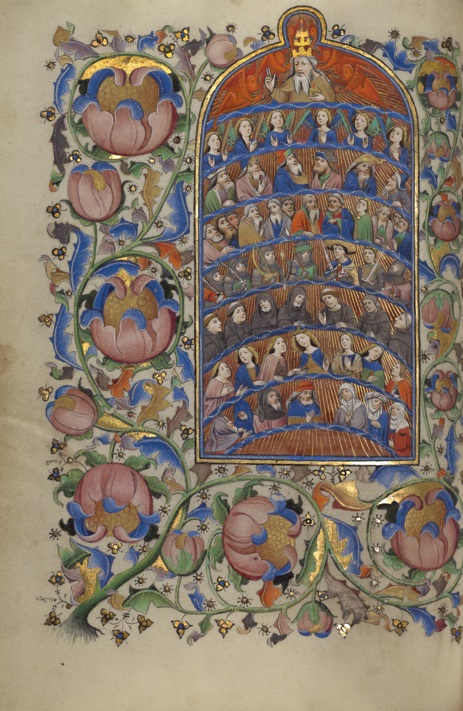

All Saints in a Book of Hours, about 1450–55, Guillebert de Mets. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 2, fol. 20v

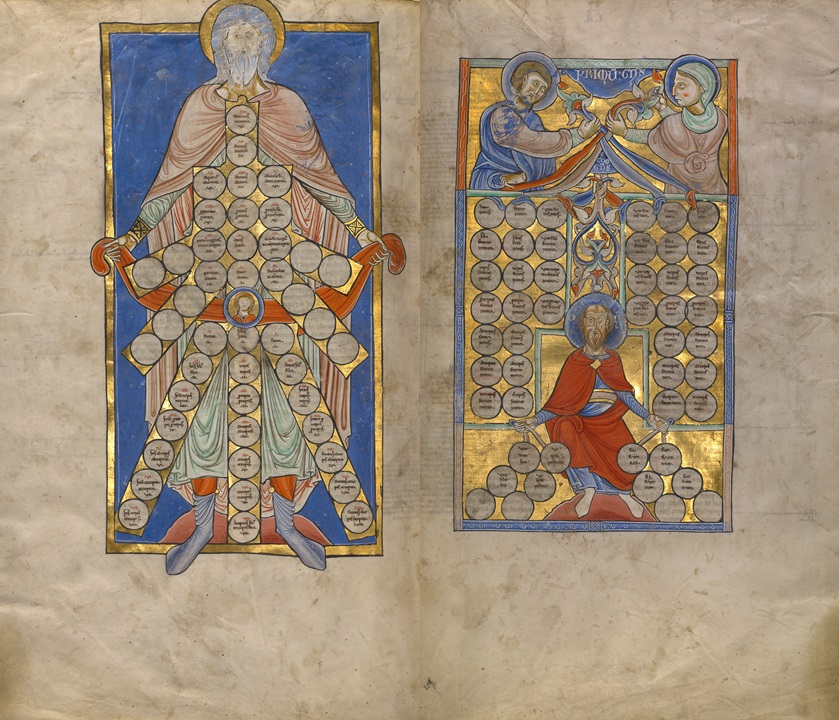

It is useful to first consider two illuminations that suggest a hierarchical relationship or social division between men and women. One of the artists of the visually rich Spinola Hours, for example, rendered a scene of All Saints as if glimpsed in heaven through a stonework frame: the male martyrs and saints are at left with the Trinity above, while the female martyrs and saints are at right with the Virgin Mary above. A closer look reveals that the men gaze heavenward towards Mary as the women look upon the Trinity, crossing the gendered divide. Throughout the premodern period, such cross-referencing of gender models was common across most levels of society in Europe. In another Book of Hours, the artist Guillebert de Mets depicted a stratified cosmos, with God atop a series of heavenly spheres, which are occupied by angels, prophets, apostles, male martyr saints, male cleric-saints, female saints, and finally the men and women of society. This hierarchy would suggest that proximity to the divine coincides to some degree with gender. Interestingly, the angels closest to God the Father have often been considered to be genderless. Despite such divided representations, women fulfilled numerous important roles in society and in popular imagination at the time—themes that will be explored in the upcoming Getty Museum exhibition Illuminating Women in the Medieval World (June 20–September 17, 2017). Yet it would be difficult to debate the fact that women today enjoy many more freedoms than they did in the Middle Ages. Another way to visualize male-female relationships in the Middle Ages and Renaissance is through matrimonial diagrams in legal manuscripts. The Tables of Consanguinity and Affinity shown below, for example, display the degrees of separation between a person and his or her blood relatives (to prevent incest) and relationships to one’s spousal family members (to determine inheritance), respectively. But almost every iteration of human sexual interaction imaginable existed beyond these images and stratified hierarchies, and not all intimate acts were for the purpose of procreation.

Tables of Consanguinity and Affinity in Gratian’s Decretum, about 1170-80, unknown illuminator. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIV 2, fols. 272v–273

Unmentionable Vice(s)

Finding evidence of a variety of sexual behaviors in medieval and Renaissance art is difficult for the simple reason that sex was rarely depicted. Yet, sometimes these omissions can themselves be evidence.

A Priest and Guy’s Widow Conversing with the Ghost of Guy de Thurno (detail) from The Visions of the Soul of Guy de Thurno, 1475, Simon Marmion. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 31, fol. 7

A beautifully illuminated manuscript in the Getty’s collection, The Vision of the Soul of Guy de Thurno depicts a scene in which Guy’s ghost returns to his wife to urge her to repent for a sin they had committed. Although this act is never visualized or represented within the manuscript, Robert Sturges has argued that the sin is sodomy. It should be noted that, while that term could refer to a specific act, the medieval conception of sodomy also often included any act or position that did not have the possibility of procreation. The organization of the composition speaks where images and words are silent. To the far left (perhaps a double entendre referring to the Latin word sinister) of the composition is the marital bed, now purified by two holy books. To the right is a group of five men and Guy’s widowed wife. At the center of this miniature is the priest who interrogates the soul of Guy de Thurno. We cannot see the soul; instead we are faced with the empty bed to the left and the empty silence of the interrogation to the right. As Diane Wolfthal has explained, “Sodomy, the sin that cannot be named, apparently cannot be visualized either.”

Rubbed Out: Caressed Crucifixions and Copulating Couples

Books have always been intended for touch, as hands have historically manufactured, opened, held, and manipulated these bound objects. Illuminated manuscripts often led especially eventful lives, since each new owner could potentially alter the codex with marks of possession or by leaving signs of haptic usage (dirty pages).

The Crucifixion, begun after 1234, completed before 1262. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig V 5, fol. 104v; The Crucifixion, about 1420–30, Master of the Kremnitz Stadtbuch. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig V 6, fol. 147v

In a thirteenth-century Missal in the Getty collection, the body of the crucified Christ was repeatedly touched in the past for devotional purposes. Another Missal, from the fifteenth century, includes an osculation plaque beneath The Crucifixion, and this roundel with the risen Christ was specifically meant for kissing. In these examples, the parchment page becomes a vehicle for connecting sensate, humanly bodies with the divine presence. In other instances, physical contact with the pictorial field was meant to obfuscate visually unsettling or unsavory content, at times found in secular manuscripts. (See the Further Reading for considerations of masculine and feminine characteristics in medieval and Renaissance Crucifixions, and specifically Leo Steinberg’s controversial book The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion.)

Duke Albrecht IV the Wise and His Wife Kunigunde of Austria Adoring the Virgin and A Scribe and a Woman in Rudolf von Ems’ World Chronicle, 1487. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 33, fols. 2v–3

The World Chronicle by the German scholar Rudolf von Ems, written in the thirteenth century, constructed a view of Judeo-Christian and Greco-Roman history from the creation of the world to the author’s present time. In the first decade of the fifteenth century, a noblewoman likely from Bavaria (in present-day Germany) received a luxury copy of the text filled with beautiful illuminations depicting major narrative episodes from history. By about 1487, the manuscript entered the collection of Duke Albrecht IV the Wise and his wife Kunigunde of Austria, whose portraits were added kneeling in piety before the Virgin Mary on a page that now faces the image of the previous female owner. At some point during the manuscript’s history, a reader-viewer physically rubbed out several painted figures, specifically those individuals shown nude or engaged in extramarital sexual activity.

God with Adam and Eve in Rudolf von Ems’ World Chronicle, 1487. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 33, fol. 5

This phenomenon does not mean that every unclothed figure has been smudged out of history: Adam and Eve, for example, have indeed had their nether regions blurred from touch in the opening image of creation, but a few pages later, the couple appears twice—the first time nude (though not necessarily sexed) while eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, and the second time being expelled by an angel from Paradise (and covering themselves with fig leaves). The unknown illuminator included four sexual scenes throughout the rest of the manuscript: the first shows the patriarch Abraham and his concubine Hagar; the second represents Lot engaging in incestuous relations with his daughters; the third depicts part of a larger orgiastic scene between Israelites and Midianites (a man and woman from each group were viciously murdered, through the groin, while fornicating); and the fourth of Amnon raping Tamar. Three of these copulating couples were completely eviscerated, right down to the parchment layer. It is puzzling to consider why the moment of incest was left untouched. One possible reason explaining the other erasures is that those relationships were interracial or interfaith encounters, rather than purely familial (although Tamar was Amnon’s half sister), and the erased images appear to have shown the couples having sex.

Abraham Making Love to Hagar; Lot’s Incest; Pinehas Kills Simri and Kosbi; Amnon Raping Tamar in Rudolf von Ems’s World Chronicle, about 1400–10. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. 33, fols. 29, 32, 107v, 194v

The above images fit within the section of the manuscript on ancient history, as does the story of King David of Israel, who lusted after a married woman named Bathsheba. One day, while Bathsheba was bathing, David saw her naked body and became inflamed with passion for her. In the illumination, David enters a private chamber where Bathsheba washes her body, which has been stroked by an owner at some point in time to effectively obscure her vagina while leaving her breasts untouched. By smearing the offensive paint layer, the owner effectively pressed flesh to flesh in an act not dissimilar to frottage, since the manuscript page is in fact skin (parchment, from animals).

David and Bathsheba in Rudolf von Ems’s World Chronicle, about 1400–10. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. 33, fol. 191v

Given the prudish proclivity for censorship of a one-time owner, it is curious that the two-page spread related to the story of Sodom and Gomorrah has not been altered in any way. The illuminations do not depict any scene of homo-social/-sexual encounter, inhospitality towards strangers, or violence, all of which are typical associations with or interpretations of this story. Moreover, in other illuminated copies of Rudolf von Ems’s text, the Sodomites appear as armed warriors, ready to forcefully engage with Lot’s three angelic visitors. As Robert Mills points out in his book Seeing Sodomy in the Middle Ages, there were myriad encounters that could be characterized as sodomitical, though it is unclear whether any of those associations were made with the images in The World Chronicle.

Same-Sex: Homosocial or Homosexual?

Initial A: Saints Maurice and Theofredus, about 1460–80, Frate Nebridio. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 91, recto

Same-sex bonds of friendship or communal loyalty can be found in numerous premodern contexts, from military to monastic to mendicant and others. Saints Maurice and Theofredus—third-century CE soldiers of the Sacred Band of Thebes in North Africa and Christian martyr-saints—are among the faces of the past who had a homosocial relationship, involving friendship, fidelity, or a bond among members of the same sex (a bromance, so to speak, but on a deeper level). Some scholars have suggested that the oath of brotherhood taken by the Theban Legion was purely homosocial, but others hint that sexual encounters may have taken place between Maurice and his companions (see James Neill in the Further Reading). Still, the virtue of loyalty that the soldiers demonstrate likely appealed to the Augustinian nuns, who once beheld the miniature shown above in a choir book.

The Torment of Unchaste Monks and Nuns in The Visions of the Knight Tondal, 1475, Simon Marmion. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 30, fol. 24v

By contrast, unchaste monks and nuns are the subject of a miniature that describes the knight Tondal’s journeys through the afterlife. As punishment for their lust, the souls are devoured by a frightening beast and excreted into a frozen lake in Hell. Although we do not know the nature of their sexual encounters, it is poignant that their sins resulted in both men and women becoming pregnant with entrail-eating monsters. While this illumination depicts those guilty of breaking their vows of chastity, the punishment is doled out to anyone guilty of lust. This text and the one about Guy de Thurno mentioned above were once bound together with a third text on Saint Catherine of Alexandria, commissioned by Margaret of York, duchess of Burgundy and wife of duke Charles the Bold. In medieval Silesia (present-day Poland), Saint Hedwig lived a Christlike life, including taking a vow of chastity and entering a convent after her husband was killed. She eventually committed her daughter, Gertrude, to a similar bond of sisterly devotion. Chaste living meant renouncing carnal pleasures or desires, including sexual activity and other temptations of flesh and mind. Examples abound in the premodern period of married couples taking vows of chastity in order to focus purely on spiritual devotion. Delphine de Signe of Naples and her husband Elzéar de Sabran had one such arrangement. They looked to Saints Cecilia and Valerian as models of total pious living.

Saint Hedwig Presenting Her Daughter, Gertrude, to the Convent of Trebnitz from The Life of the Blessed Hedwig, 1353. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XI 7, fol. 18v

In the tale of the knight Gillion de Trazegnies, after being tricked into thinking that his wife Marie had died while he was prisoner in Egypt, Gillion marries the Sultan’s daughter, Gracienne. Eventually, Gillion’s sons locate him and report that Marie is still alive. In a twist of fate, both wives renounce their sexual obligations within the confines of marriage and jointly commit to enter a convent together. As medieval French literature specialist Zrinka Stahuljak explains, this episode can be read as “queer” vis-a-vis the institution of marriage. Equally queer was the sight beheld by the text’s author that inspired the tale: a tomb with a knight flanked by two nuns. Homosociality can be found in unexpected corners of premodern literary and ecclesiastical culture.

Transgendering History

Bagoas Pleads on Behalf of Nabarzanes in The Book of the Deeds of Alexander the Great, about 1470–75, Master of the Jardin de vertueuse consolation. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIV 8, fol. 133v

Some subjects were deemed unfit for medieval readers and were therefore altered. For example, the world ruler Alexander the Great had a range of lovers or companions, including the young man Hephaistion. In the Middle Ages, numerous accounts of Alexander’s life were produced, from France and Byzantium to Persia and India. In a version written by a Portuguese humanist for the Burgundian court, Alexander’s handsome eunuch-lover Bagoas is cast as a beautiful woman, called Bagoe, in order to “avoid a bad example,” as the author phrased it. Throughout an illuminated copy of the text at the Getty, Bagoas/Bagoe wears lavish garments. In one instance, her ability to influence Alexander’s decisions—as a seductive or persuasive woman—is contrasted with the warrior-like Amazon women, who desire to bear a child by Alexander. This transgendering or re-gendering was not only more acceptable but also reaffirms the impossibility of creating straightforward categories or binaries. As we have seen, medieval authors and artists often made considerable changes to well-known and beloved stories. Readers and viewers understood these alterations as part of the process of history writing, or more precisely, of moralized and multiple-perspective histories.

The Limits of Labels and the Breakdown of Biography

The Embassy of the Duke of Brabant before the King of France and the Duke of Berry in Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, about 1480–83, Master of the Getty Froissart. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIII 7, fol. 272v

Rumor and hearsay can affect the arc of history and memory just as much as religious dogma or public policy. The chronicler Jean Froissart recorded the Hundred Years’ War in multiple volumes, providing artists with ample material for depicting bloody battles, embassy encounters, or even contemporaneous courtly costume. In a chapter concerning negotiations between the King of France and representatives of the Duke of Brabant, Froissart relates that Jean, Duc de Berry, was infatuated with a boy at court who specialized in manufacturing knitted undergarments. The artist of the Getty’s copy of the text chose to include the duke placing his hand on the youth’s shoulder (known as his “favorite”), as the two appear to be moving into the shadows of the throneroom. Froissart’s “outing” of the French bibliophile would later inspire art historians to interpret images in books owned by the duke to reveal his homosexual desires (see Further Reading). However, these images were often overlooked by early art historians, who chose to focus on other aspects of the great collector and bibliophile. While it is would be terribly essentializing to suggest that every study of the Duc de Berry should consider his sexuality, it has also been all too easy for art historians to simply omit or avoid this challenging topic, creating still more silences and invisibilities.

“[Giovanni Antonio Bazzi] was a carefree and licentious man, keeping others entertained and amused with his manner of living, which was far from creditable. In which life, since he always had about him boys and beardless youths, whom he loved more than was decent, he acquired the nickname of Sodoma; and in this name, far from taking umbrage or offense, he used to glory, writing about it songs and verses in terza rima, and singing them to the lute with no little facility.” —Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, 1568

Christ Carrying the Cross, about 1535, Giovanni Antonio Bazzi (Sodoma). The J. Paul Getty Museum, 86.GA.2

It is tempting to read an artist’s biography into his or her artworks, yet such an approach must be applied thoughtfully and cautiously. For example, is there a potential “gay” (or sodomitical) underpinning to Giovanni Antonio Bazzi’s drawing of Christ Carrying the Cross, given that the artist appears to have loved boys and men “more than was decent,” as we are told by Vasari? The present authors have cringed in museum galleries when tour guides or visitors fixate on Giovanni Antonio’s biography to the point at which a drawing like the one above, or a painting of The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, is reduced to testing a visitor’s gaydar, so to speak. Similarly cringe-worthy conversations are often had about the “masculine” female figures in Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel (Vatican City) or sculptures in the Medici Chapel (Florence). Renaissance Florence, where both Giovanni Antonio Bazzi and Giorgio Vasari lived, had a reputation for sodomy, so much so that “The Office of the Night” was established to investigate all charges of these behaviors. As Michael Rocke, a scholar on this period, has pointed out, same-sex sexual encounters were as pervasive there as drinking, gambling, and fluid sexuality of single male culture. Accusing someone of sodomy was a powerful political weapon, a fact likely known and exploited by Vasari. Although these “records” of sodomy provide data, it can still be difficult to know whether those accused were simply at political odds with leaders, unwelcome foreigners, participants in a range of sexual activities not leading to procreation, or perhaps, like Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, appropriating a negative stereotype in order to redefine its meaning.

Sanctity Homoeroticized

Images of Saint Sebastian in the Getty Museum collection: Master of Sir John Fastolf, about 1430–40 (Ms. 5, fol. 36v); Georges Trubert, about 1480–90 (Ms. 48, fol. 173v); Gaspare Diziani, about 1718 (2004.83); Anthony van Dyck, about 1630–32 (85.PB.31); Vicente López y Portaña, 1795–1800 (2000.47); Unknown British photographer after Gudio Reni, about 1865–85 (84.XP.1411.62).

The third-century, middle-aged Roman soldier-martyr Sebastian, who by the fifteenth century began to be represented as a muscular youth wearing only a loincloth, has become something of a gay icon. Saint Sebastian was one of the plague saints, believed to protect individuals and communities from pandemics symbolized by the arrows that pierced his body. Devotion to the saint increased following the Black Death (1348), and images of his toned body and serene expression in the face of tremendous torture and imminent death have a lasting appeal for the gay community today, especially in the wake of the AIDS pandemic of the 1980s. Masculine beauty. Homoerotic desire. (Possible) Sado-masochistic appeal. These are among the associations that arise in scholarly discussions about Sebastian (who also appealed to women, according to a famous legend by Vasari in which a painting of the saint by Fra Bartolommeo supposedly caused women to sin just by the sight of it). Many of the accounts of the saint’s life include a dramatic revelation of his Christianity, becoming a sort of “coming out” narrative or tale of confession. In one sense Sebastian replaced classical myths of same-sex attraction or sexual encounter, such as Ganymede and Zeus narratives of same-sex love, that engage questions of homosexual identity. There is no proof for these layers of meaning in Sebastian’s life, only in the power of the symbol he has become.

Queering the Present of the Past

The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian in the Prayerbook of Charles the Bold, Lieven van Lathem. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 37, fol. 29; Saint Sebastian, Ron Athey, 1999 (screenshot from YouTube.com); Decorated Text Page in the Praybook of Charle the Bold, Lieven van Lathem. J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 37, 32v; Self-Portrait, N.Y.C., Robert Mapplethorpe, 1978. Jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; partial gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the David Geffen Foundation. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Saint Augustine wrote that the present exists in three forms: the present of past things, the present of present things, and the present of future things. Although “medieval” and “modern” are often conceived of as antagonists, art historians Alexander Nagel, Roland Betancourt, and others have argued that certain themes have traversed time and artistic practice. The intensity of Robert Mapplethorpe’s gaze and unapologetic self-penetration in Self-Portrait, N.Y.C., for example, fits within the long tradition of hybrid figures in medieval marginalia. These creatures are at times menacing, at others humorous or absurd, and they can even be symbolic. Indeed, Mapplethorpe thrust the marginal—that is, counter- or sub-cultural, perverse, or fetishistic—into the mainstream, while he simultaneously became a demonlike figure in his self-portrait with a bullwhip. The line between art and pornography had been crossed, and despite the Culture Wars of his time, his self-portrait has endured as poignant evidence of art’s potential to shape or influence viewer expectations. The image was recently witnessed by record crowds and rave reviews at the Getty and at LACMA in Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium. Performance artist Ron Athey transforms the violent, abject, and gut-wrenchingly painful or filthy into a manifesto in which sacred and scatological merge in order to confront preconceived notions about the body, masculinity, sexual orientation, and extreme sexual acts. When asked to describe his St. Sebastian and St. Sebastiane (feminizing the name of the male saint), Athey has said, “I make arrows out of very long medical needles and insert the metal into the head, which causes a lot of bleeding. So really it’s a sort of bloodletting performance. Some longer performances from the ‘90s, like the Torture Trilogy, included scarification, flesh hooks, branding, anal penetration, surgical staplers—an entire palette of things, some of which I still use. I guess I always play either with flesh or with fluid or blood in my work.” Both Mapplethorpe and Athey were familiar with the potential meaning, dogma, and spiritual significance behind the images referenced in their art, and yet their works transcend even those categories and have helped break down boundaries of high and low art, and have given representation to subjects once censored or erased from public view. Invisibility and erasure are constant challenges in illuminating queer lives and experience from the premodern world. However, these omissions also provide an opportunity for the careful observer to think critically about things left unsaid and unseen. Although the academic community was relatively slow to turn scholarly attention to these topics, there is now a growing body of literature on queerness in the Middle Ages and beyond. We hope that by examining these narratives, negatives, and voids in medieval and Renaissance art, we have given some presence to queer identity and fluidity in a historical context. _______

Further Reading

Links to scholarly articles, essays, and lectures related to LGBTQ+ medieval histories here

Brown, Judith C. and Robert Charles Davis, eds. Gender and Society in Renaissance Italy. 1998.

Burger, Glenn and Steven Kruger, eds. Queering the Middle Ages. The University of Minnesota, 2001.

Bynum, Caroline Walker. Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1984.

Camille, Michael. “‘For Our Devotion and Pleasure’: The Sexual Objects of Jean, Duc de Berry,” Art History, vol. 24, no. 2 (2001), 169–194.

Camille, Michael. “Play, Piety, and Perversity in Medieval Marginal Manuscript Illumination,” in Mein ganzer Körper ist Gesicht: Groteske Darstellungen in der europäischen Kunst und Literatur des Mittelalters, eds. Katrin Kröll and Hugo Sterger (Fribourg, 1994), 171-192.

Ferentinos, Susan. Interpreting LGBT History at Museums and Historic Sites. London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

Guynn, Noah. Allegory and Sexual Ethics in the High Middle Ages. Palgrave MacMillan, 2007.

Halsall, Paul. “The Experience of Homosexuality in the Middle Ages,” in Fordham University’s Medieval Sourcebook, 1998.

Kay, Sarah, and Miri Rubin. Framing Medieval Bodies. Manchester University Press, 1994.

Kaye, Richard. “St. Sebastian: The Uses of Decadence,” in A Splendid Readiness for Death: St. Sebastian in Art, exh. cat. (Vienna, 2004), 11–16.

Killermann, Sam (ItsPronouncedMetrosexual.com), The Genderbread Person, on the differences between genderqueer, gender expression, biological sex, and sexual orientation.

L’Estrange, Elizabeth, and Alison Moore, eds. Representing Medieval Genders and Sexualities in Europe: Construction, Transformation, and Subversion, 600–1530. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, 2011.

Lochrie, Karma, Peggy McCracken, and James A. Schultz, eds. Constructing Medieval Sexuality, Medieval Cultures, vol. 11. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Medievalists.net. Same-Sex Relations in the Middle Ages, 2011.

Mills, Robert. Seeing Sodomy in the Middle Ages. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Neill, James. The Origins and Role of Same-Sex Relations in Human Societies. McFarland Press, 2008.

Parkinson, R.B. A Little Gay History: Desire and Diversity Across the World. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Rocke, Michael. Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Spear, Richard E. The “Divine” Guido: Religion, Sex, Money, and Art in the World of Guido Reni. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Steinberg, Leo. The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Whittington, Karl. “Queer,” in Studies in Iconography (special issue on “Medieval Art History Today: Critical Terms”) 33 (2012), 157–168.

Wolfthal, Diane. In and Out of the Marital Bed: Seeing Sex in Renaissance Europe. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010.

Comments on this post are now closed.