Shopping in midcentury style: Detail from an elevation for Sears, Roebuck and Co. by Karl Schneider, 1942–45. Graphite and colored pencil on tracing vellum. The Getty Research Institute, 850129

Some time ago, I saw a headline in the Wall Street Journal that read “In Retreat, Sears Set to Unload Stores.” It seems that Sears is cash strapped and needs to raise over $700 million, so selling its stores is probably good business sense. But I found this to be pretty gloomy news.

No, I never worked at Sears, and I do not own Sears stock. Until recently, I only thought of Sears if I was in the market for a washing machine. But a couple of years ago I dove into the Karl Schneider archive at the Getty Research Institute, and Sears has never looked the same to me. In the course of conducting research on Schneider, I came to understand the enormous innovations that Sears (officially Sears, Roebuck and Co.) pioneered in product development, retailing, and store design. What most others think of as the most mundane of retail establishments is, for me, connected to the great architectural and design movements of the 20th century.

Schneider, a German-born architect and designer, worked at Sears from 1938 until 1945. Prior to coming to the U.S., he worked with visionary architects such as Walter Gropius (1912–1914) and Peter Behrens (1915–1916). He then established his own firm designing houses, apartment buildings, gas stations, factories, theaters, and large-scale housing estates, all with the geometric arrangement of volumes, smooth, unornamented surfaces, and expressive use of plate glass that characterized the International Style. He brought a functionalist aesthetic to the offices of Sears.

Founded as a mail order company, Sears opened its first brick and mortar store in 1925. At first, they had no idea what they were doing. They simply opened up the ground floor of a mail distribution center to the public. There was no thought given to merchandising or customer service. As the company grew, their merchandising and store design became increasingly sophisticated. Schneider began his brief but prolific career at Sears in the Merchandising Testing and Development Department, where he designed appliances, tools, furniture, toys, and housewares.

Design for Drip Coffee Maker, Karl Schneider, June 12, 1942. Graphite and colored pencil on tracing vellum. The Getty Research Institute, 850129

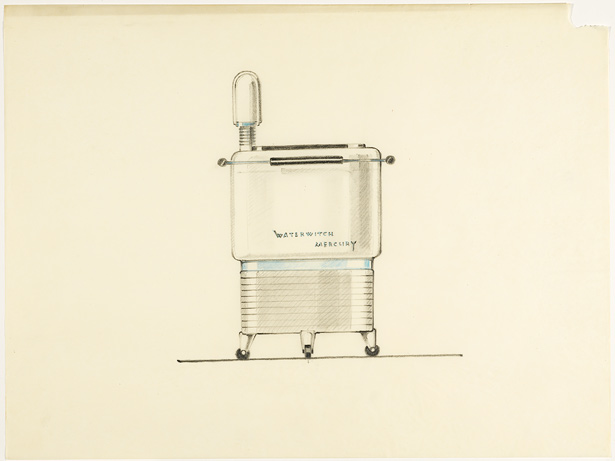

Design for Mercury Waterwitch Washing Machine, Karl Schneider, 1938–1942. Graphite and colored pencil on tracing vellum. The Getty Research Institute, 850129

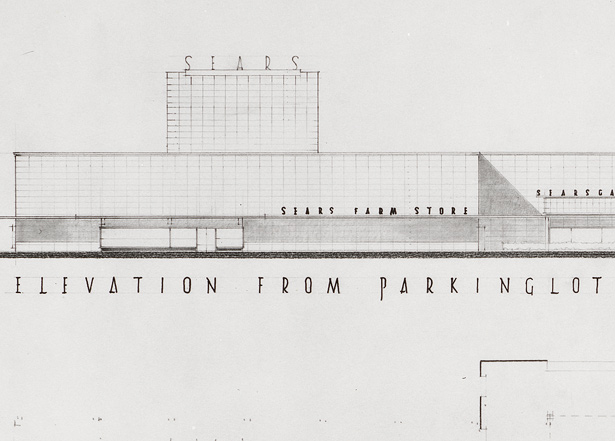

In 1943, he moved to the Store Planning and Display Department, where every detail of the store’s interior and exterior was scrutinized. At the time, double-digit profits propelled Sears’s rapid and widespread expansion (and employees who had participated in the company’s progressive profit sharing plan became exceedingly wealthy!). Schneider’s architectural drawings show that standardization was a key element of their building strategy. He drew upon his experience designing modular furniture and standardized housing in Germany. His design for a sprawling “standard” store in Chicago, as seen from the parking lot, also shows the importance Sears placed on suburban locations where large properties could be obtained, and their recognition of the automobile as an increasingly important factor in the consumer experience.

Standard Sears Store, Elevation from Parking Lot (with detail shown below), Karl Schneider, 1942–45. The Getty Research Institute, 850129

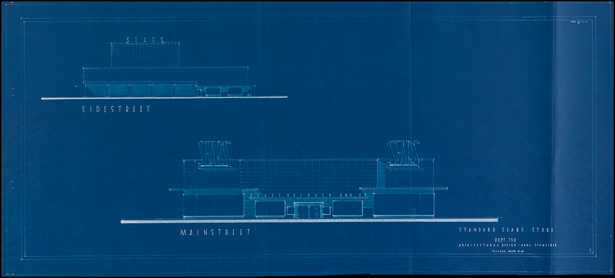

Standard Sears Store, Side Street and Main Street Elevations, Karl Schneider, March 16, 1944. Blueprint. The Getty Research Institute, 850129

While he worked on many imaginative proposals for urban sites, some of which depict streetcars or high-rise residences, most drawings relate to “standard” store designs. Throughout World War II, Sears had to scale back on its building campaign, but Schneider spent this time methodically working out the details for the standard store.

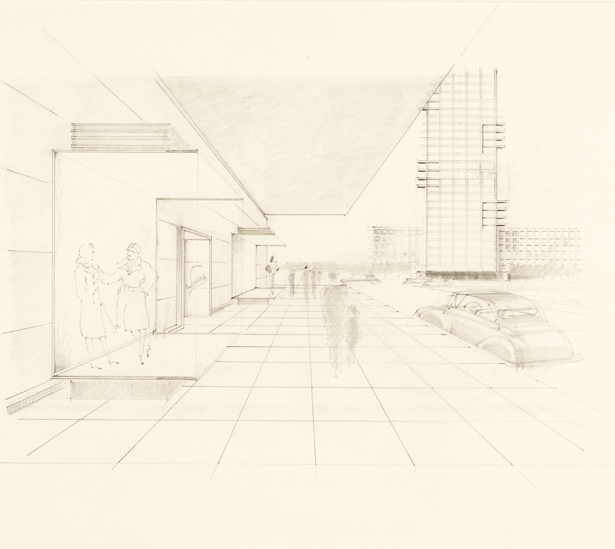

Elevation, Sears, Roebuck and Co., Karl Schneider, 1942–45. Graphite and colored pencil on tracing vellum. The Getty Research Institute, 850129

Pedestrian View of Sears Street Elevation, Karl Schneider, 1942–45. Graphite on tracing vellum. The Getty Research Institute, 850129

He also designed a scheme for prefabricated store fronts in three sizes, which may have corresponded to the three types of stores Sears built (A stores had the most square feet and carried the greatest variety of merchandise, while B and C stores were smaller and carried fewer items). The new facades and standard stores featured symmetrical arrangements of large plate glass windows and surface treatments that would have conveyed European modernism, illustrating the widespread adoption of modernism as a vernacular style for commercial architecture.

Prefabricated Standard Fronts, Karl Schneider, 1942–45. The Getty Research Institute, 850129

Early in 1945, Schneider left Sears to work as an associate architect with the Chicago firm Loebl and Schlossman. That same year, Sears’s sales exceeded $1 billion. Their expansion campaign continued, and in 1959 they created a subsidiary that developed shopping centers in which Sears was one of the dominant stores. In 1973, Sears Tower opened in downtown Chicago. Over 100 stories high, it is still one of the tallest buildings in the western hemisphere.

But this is the apex of the Sears story—at least architecturally. In 1994, Sears Tower (now named Willis Tower) was sold and the company headquarters moved to a nondescript business park outside Chicago. Now Sears is ready to unload its stores and begin yet another stage in the deconstruction of its iconic architectural identity. Remaining stores, according to recent comments from Sears’s new merchandising chief, will be revamped in an effort to attract new (“young”) customers and win back past shoppers.

Who are the designers behind the sleek new looks already being rolled out at select stores? Will the company find its 21st-century Karl Schneider? I look forward to visiting my local Sears store, which happens to be a landmark 1947 Streamline Moderne building, to find out.

Sears in Santa Monica: A classic of midcentury modern architecture. Photo: M P R on Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

See all posts in this series »

Very interesting information about both Sears and Karl Schneider. Would he have ever sketched/drawn the Art Institute? If so, I may have one of his pieces.

I have come across an Art Institute sketch signed by a “Karl Schneider,” but do not believe it’s the same Schneider that worked for Sears and is the subject of this post.

Thanks for your article, Marlyn. It’s interesting to see some of Karl Schneider’s U.S. work for Sears. I live in Hamburg, Germany with what’s left of Schneider’s architecture within reach. Most of it still exists – especially his appartment blocks – but the Roemer house from 1928 for instance was pulled down as late as the 1980s when long-forgotten Schneider was slowly getting re-discovered. The same fate had awaited his most innovative work from 1923 – the famous Michaelsen house which was saved just in time in 1986. It’s a sad thing that Schneider died at the early age of 53, when he was just about to start working again as an architect. And it’s a shame that after the end of the Nazi rule it took Hamburg so long to give him again the attention that he deserved. The buildings he designed are on the same level as those by Gropius or Mies van der Rohe!