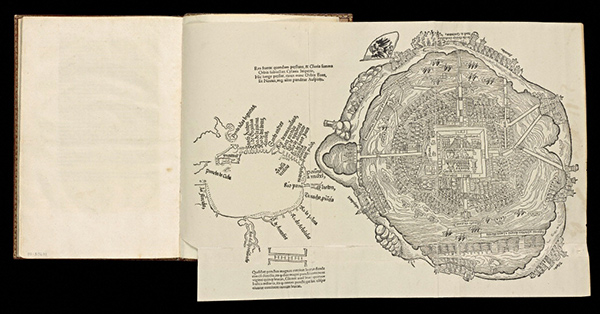

Aztec ceremonial precinct in Tenochtitlanin (today the Zócalo, Mexico City’s main square) depicted soon after the Spanish Conquest. Detail from Tenochtitlan, woodcut in Hernán Cortés, Cartas de relación (Nuremberg, 1524). The Getty Research Institute, 93-B9631

Throughout 2013, the Getty community participated in a rotation-curation experiment using the Getty Iris, Twitter, and Facebook. Each week a new staff member took the helm of our social media to chat with you directly and share a passion for a specific topic—from museum education to Renaissance art to web development. Getty Voices concluded in February 2014.—Ed.

The official language of Mexico is Spanish—this everyone knows. Few, however, know that Mexico also recognizes 68 indigenous languages spoken within its borders and even has a national institute devoted to their study. Many of these languages are spoken here in Los Angeles as well: an estimated 50,000 Angelenos, for example, speak Zapotec, an indigenous language from the state of Oaxaca.

In Mexico, Nahuatl (pronounced NAH-wat), the language of the Aztecs and a lingua franca in the early 16th century at the time of the Spanish Conquest, still counts over 1.3 million speakers—the largest indigenous group in Mexico today. English has a surprising number of Nahuatl loanwords, such as avocado (ahuacatl), tomato (tomatl), and chocolate (cococ + atl, literally meaning “bitter water”), which were transmitted to Europe by Spanish conquistadors, friars, and explorers.

These facts illustrate that the study of the Pre-Columbian and Latin American colonial past is incredibly relevant to present-day Los Angeles—as the next iteration of Pacific Standard Time, focusing on Latin America and L.A., will more fully reveal. Mexico’s linguistic diversity, moreover, bespeaks its over 3,000 years of cultural and artistic richness. One episode from Mexico’s rich history, the cultural encounter between its indigenous population and the Europeans who arrived there in the 1500s, is visually illustrated in books and prints displayed in the first section of our newly installed exhibition Connecting Seas: A Visual History of Discoveries and Encounters, on view at the Getty Research Institute from Saturday, December 7, through next April 13.

In 1519, when the Spanish conquistadors under the leadership of Hernán Cortés first encountered the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan, they were enchanted by its beauty and magnitude. They marveled that the splendid buildings and sacred structures of this fabled city, built upon an island in the Lake Texcoco, were all constructed of masonry and lavishly decorated. In his memoirs, Spanish soldier Bernal Díaz del Castillo described his amazement when he and the company of fewer than four hundred men beheld the capital for the first time:

…when we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land and that straight and level Causeway going towards Mexico, we were amazed and said that it was like the enchantments they tell of in the legend of Amadis, on account of the great towers and cues and buildings rising from the water, and all built of masonry. And some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream. It is not to be wondered at that I here write it down in this manner, for there is so much to think over that I do not know how to describe it, seeing things as we did that had never been heard of or seen before, not even dreamed about.

—Bernal Díaz del Castillo, The True History of the Conquest of Mexico

The map of Tenochtitlan shown below, published in 1524 with the first Latin edition of conquistador Cortés’s letter to the Spanish king, documents these wonders, including the twin pyramids of the sacred precinct, which the Aztec considered the cosmic center. However, by the time of the book’s publication, the Spaniards had already conquered and leveled the city, establishing Mexico City as the capital of New Spain. Today, the ruins of the Aztec capital are buried under the sprawling metropolis of Mexico City, though the twin pyramids of the Templo Mayor have been excavated and are visible next to the Zócalo, the city’s main square.

Tenochtitlan, woodcut in Hernán Cortés, Cartas de relación (Nuremberg, 1524). The Getty Research Institute, 93-B9631

The Aztecs established Tenochtitlan in 1325 after years of migration. According to Aztec myths, their ancestors originated in a place called Aztlan (Nahuatl for “Place of Herons”), thought to be located in northern Mexico. By the order of their patron deity, Huitzilopochtli, they migrated to Central Mexico. A second map in the exhibition depicts this legendary migration. On the right, a group of people leaves Aztlan, represented as a temple with a heron beside it; after wandering along a long meandering path, they arrive at a prominent hill topped by a grasshopper—the place-sign for Chapultepec (“Hill of the Grasshopper”), today a district in Mexico City. Below the hill and depicted upside-down is a large cactus designating the place Tenochtitlan (“Place of the Cactus from the Stone”), the Aztec capital.

Aztec Migration and Founding of Tenochtitlan, engraving in Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri, Giro del mondo, vol. 6, Nuova Spagna (Naples, 1699–1700), pl. facing p. 38. The Getty Research Institute, 2698-167.v6. Gift of the Getty Research Institute Collections Council

This map of the Aztec migration was published in the 1600s by Italian voyager and author Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri, whose five-and-a-half-year journey across Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and the New World likely inspired Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days. Careri copied this map from a version made about a century earlier and found in the collection of Creole historian Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, who gave Careri access to his illustrated manuscripts. Sigüenza’s original map has been digitized and can be viewed at the World Digital Library.

The Spanish Conquest ushered in massive changes to Mexico’s linguistic, cultural, physical, and spiritual landscape, changes that find strong echoes still today. As we illustrate in the exhibition, the Conquest was also part of a centuries-long human epic of navigation, exploration, and conquest that brought, and continues to bring, culture, language, art, and technology into contact across the seas.

Detail of Aztec Migration and Founding of Tenochtitlan showing Chapultepec (“Hill of the Grasshopper”) at center. The small, upside-down opuntia cactus below the hill designates Tenochtitlan (“Place of the Cactus from the Stone”), the Aztec capital.

Comments on this post are now closed.