“Don’t you have enough pictures of rocks?” complained the teenager to his dad taking photos of the Grand Canyon. I laughed. You can never have enough pictures of rocks, I thought. Especially rocks as beautiful and awe-inspiring as these. Looking at the amazing range of colors of the rocks, from red to orange to yellow to green to blue, you understand why artists have long turned to rocks—or, to be more precise, minerals—to make pigments.

The equally awe-inspiring and beautiful panel paintings and manuscript illuminations in the exhibition Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance are, in some ways, also pictures of rocks and minerals. Take, for example, the brilliant blue background in the leaf from the Laudario of Sant’Agnese depicting the martyrdom of St. Lawrence, which was painted with azurite, a copper-based mineral.

The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence from the Laudario of Sant’Agnese, about 1340, Pacino di Bonaguida. Tempera and gold leaf on parchment, 7 1/2 x 8 3/16 in. (19 x 20.8 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 80b, verso

The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence (detail) from the Laudario of Sant’Agnese, about 1340, Pacino di Bonaguida. Tempera and gold leaf on parchment, 7 1/2 x 8 3/16 in. (19 x 20.8 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 80b, verso

To make paint from azurite, the rocks are collected, sorted, and refined, keeping only the bluest parts. These are crushed and ground into a fine powder. The powdered azurite is mixed with a liquid binder, typically egg white for painting on parchment, or egg yolk for painting on wooden panels, to make a paintable mixture. The backgrounds in the manuscript leaf depicting St. Lawrence, and many other of the Laudario leaves as well, were painted with relatively coarsely ground azurite to give them a brilliant deep blue color. When you look at one of these passages under the microscope, it indeed looks like a field of blue rocks.

Boulder showing veins of the deep blue mineral azurite on display at the Jerome State Historic Park, Jerome, Arizona

Azurite isn’t the only mineral used to make paint. In fact, many of the paints used in 14th-century painting were made from minerals. A brilliant yellow (and toxic!) paint was made from the arsenic-based mineral orpiment. The subtle grey-green used as a base layer under flesh tones was made from the iron-based mineral terre verte, also called “green earth.” Iron earth minerals come in a variety of other shades as well, including reds, oranges, yellows, and browns—comprising the palette of colors in the canyons in southern Utah, as well as in paintings by 14th-century Florentine artists.

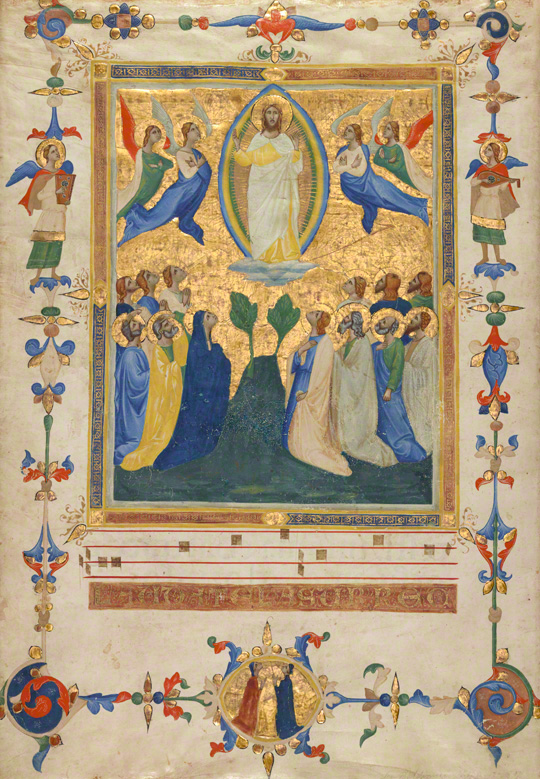

Ultramarine, another deep-blue pigment similar in color to azurite, comes from the semi-precious stone lapis lazuli found in Afghanistan. The expense of importing this semi-precious stone to Europe made it extremely expensive—more expensive than gold—and consequently, it was generally used sparingly. In the leaf from the Laudario of Sant’Agnese depicting Christ’s Ascension, Mary’s iconic blue robe is painted with a thin layer of ultramarine over base layers of azurite. Was this done to impart a richer and more distinctive tone to this important figure, or to minimize the use of the more expensive ultramarine pigment?

The Ascension of Christ from the Laudario of Sant’Agnese, about 1340, Pacino di Bonaguida. Tempera and gold on parchment, 17 1/2 x 12 1/2 in. (44.4 x 31.8 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 80a, verso

Detail of Mary’s robe showing layering of ultramarine over azurite in The Ascension of Christ (detail) from the Laudario of Sant’Agnese, about 1340, Pacino di Bonaguida. Tempera and gold on parchment, 17 1/2 x 12 1/2 in. (44.4 x 31.8 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 80a, verso

In addition to allowing artists to create a range of colors and stunning visual effects, pigments made from rocks and minerals sometimes can also tell us about the history of painting, artistic collaboration, and trade. For example, pigments made from azurite and ultramarine usually contain small traces of other minerals that aren’t completely removed during the refining process. These trace minerals may be unique to the geographic region where the mineral was mined, providing a “signature” of where the pigment came from. By comparing the trace minerals found in mineral-based pigments in works of art to those from geologic samples where the location of origin is known, scientists, conservators, and art historians can learn more about historic trade routes and artistic practices.

Too many pictures of rocks? Never.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks