Francesca Albrezzi of the Getty Research Institute provides a behind-the-scenes look of challenges faced and lessons learned in building “Digital Mellini,” the first of three projects in Getty Scholars’ Workspace, a scholarly collaboration environment that’s been described as “Wordpress for scholars.” For a previous progress update on Digital Mellini, see this post.

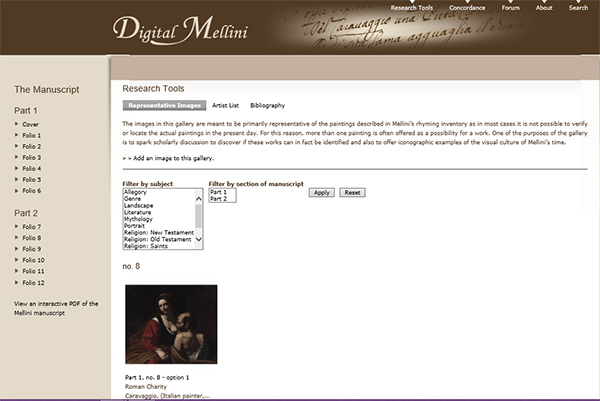

“But is it innovative?” That’s a question we’ve asked ourselves time after time about a digital humanities project we’ve been working on for almost two years. Called Digital Mellini, it’s the first in a series of projects that aim to create digital critical facsimile editions of art historical texts. Mellini uses an online collaborative working environment called the Getty Scholars’ Workspace, which the Getty Research Institute is in the process of creating.

Technically speaking, many computer whizzes might be underwhelmed by the project—a website to collectively elucidate an 17th-century paintings catalogue. However, technical innovation was not the main point of the project. In thinking critically about a sustainable project that could survive on a variety of budgets, our technical team wanted to use readily available digital tools (primarily open source) to achieve our scholarly goal of fostering and orchestrating a collaborative way of working online on art-historical objects. We’ve learned a great deal about the way art historians typically do their research, which highlights the challenges of a collaborative workflow process involving several scholars working remotely on the same project.

Art historians have very particular bodies of knowledge. Not used to collaborating (what Murtha Baca has called the “Saint Augustine Syndrome”), we on the project team observed that our scholars—Murtha, Nuria Rodríguez Ortega, Francesca Cappelletti, and Helen Glanville—would often make references to information that others within the project (such as myself and others working on research, editing, and technical issues) could not intuit as they could. While it was understood that references would be made clear during the editorial process for our public launch of the digital publication, these hanging chads often stymied the dynamic dialog we were hoping to build organically between the scholars’ annotations and comments. Think of it this way: How many people would you expect to understand a post-it note that you wrote to remind yourself about something? Probably not that many.

So what did this lesson mean for our concept of a collaborative online workspace? For myself as a research assistant, data integrator, and project manager, it meant additional work to try to fill in the information gaps as the project progressed and to devote extra forethought to anticipate pitfalls whenever possible. It also meant that our scholars, Web experts, and other research compatriots needed to clarify fragmentary information and review and rewrite critical, contextual content. Our team realized that digital collaborative projects could entail producing more work in the initial research stages in order to fill in others on the project team who might not understand the nuanced details or references. If the scholar instead started his or her work with the awareness that their reference should be complete in nature, it would better foster and encourage dynamic exchanges crucial to the concept of multi-authored, multi-voiced production. With a need to keep to a project schedule, increasing dialogue between co-authors early in the process would then allow a greater opportunity for scholastic production. This would prevent a laborious rehashing later in the project’s editorial process as well, where time becomes more and more precious.

In addition to these complexities of workflow, this project took place over a long period of time, with scholars working on it when they weren’t absorbed in other professional or quotidian matters. This made it difficult for everyone to keep their place within the project. Often, due to the fragmented and often fragmentary information-creation process, the scholars would feel disoriented when they reentered the online environment, similar to losing your place in a book that you have set down for too long without leaving a bookmark.

Our team has become very conscious of workflow and project management as key components in a truly collaborative digital production. As the publication process continues, we look forward to sharing our end product, and recycling our flowcharts and task lists to buttress and enhance our next Scholars’ Workspace projects: Digital Montagny and Digital Kirchner.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks